Genetic selection for multiple births in sheep

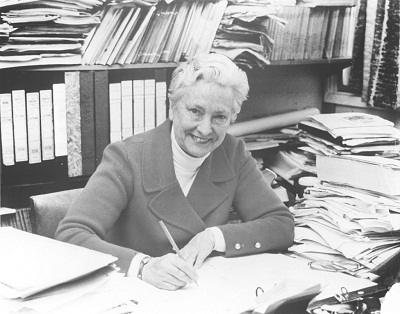

Dr Helen Newton Turner (originally an architect), radically changed merino sheep breeding in Australia. Encouraged by Ian Clunies Ross, at that time head of the McMaster laboratory, she became one of the world’s leading authorities on sheep genetics and worked with the CSIRO for over 40 years. Dr Turner led CSIRO’s sheep breeding research in the Division of Animal Genetics from 1956 until 1973. This was a golden period in sheep breeding research in Australia and the world in which she and her colleagues laid the foundations for an objective, measurement-based approach to sheep breeding, pioneering techniques that now form the basis of most sheep breeding in Australia, and have been of very great economic benefit to the country.

She proved, despite pessimism by other geneticists, that it was possible to select sheep for the ability to produce multiple births. Her research showed that big increases in lambing rates were possible, which provided graziers with more sheep for sale and more scope for genetically improving their flocks.

She received many honours and awards including election as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1977 and an Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) in 1987. In 1993, the Association for the Advancement of Animal Breeding and Genetics (AAABG) established The Helen Newton Turner Medal to perpetuate her memory. The Medal is awarded by AAABG to provide encouragement and inspiration to those engaged in animal genetics.

Early beginnings

Helen Newton Turner graduated in architecture and confidently expected it to be her career. Then, as a young graduate looking for a job, she met Ian Clunies Ross who so changed the course of her life that she will be remembered as a geneticist, and one who radically changed Merino sheep-breeding in Australia. She proved, despite pessimism by geneticists, that it was possible to select sheep for the heritable ability to produce multiple births. Her research not only showed that big increases in lambing were possible, giving graziers more sheep for sale and more scope for genetically improving their flocks, but also created a better understanding of reproduction in all animals.

As a geneticist, Helen Turner traced her lifelong fascination with mathematical order to a grandfather who was an accountant. But she did not deny the importance of acquired characteristics and believed that her co-educational schooling had a lot to do with her success in a profession that was dominated by men. She also paid tribute to her parents ‘ she could not remember a time when it was not taken for granted that she, as well as her brothers, would attend university, though the expenses involved meant considerable self-sacrifice by her parents.

Her father was an officer in the New South Wales Child Welfare Department and her mother, a teacher, one of the first women graduates from the University of Sydney. During her own course at the same university she found architectural design difficult but enjoyed the mathematical side. She graduated with honours in 1930 in the depths of the depression and could find no better job than that of a secretary in an architect’s office. It closed a year later and she worked with the New South Wales Public Service until CSIR’s McMaster Animal Health Laboratory at the University of Sydney advertised for a secretary. Her new boss was Ian Clunies Ross (who was later knighted as a CSIRO Chairman). He recognised her potential and arranged for her to go to England for a year to study statistics applied to agriculture. This was to supplement the university mathematics course she had been doing at night.

Early work at CSIRO

In 1939 Helen Turner returned to the McMaster Laboratory as a technical officer. She recalled:

It was a fantastic place to work in. Everybody was under 35 and Clunies Ross was the kind of person who brought out the best in them. I was inspired by the atmosphere of the whole place.

But the war changed her outlook. Her work seemed increasingly futile as her men friends went off to fight. She switched to the Department of Home Security in Canberra and, after her brother’s death at El Alamein, to the Directorate of Manpower which was being run by Ross.

The war over, she returned as a consulting statistician to her old Division which had been expanded to include both Animal Health and Production. She became closely involved with Merino breeding experiments being carried out under diverse conditions at the Division’s research stations at Gilruth Plains, near Cunnamulla in south-western Queensland, at Armidale in the New England region of New South Wales and at Deniliquin in the Riverina, NSW. The office-in-charge of animal breeding in CSIR at that time was Dr RB Kelley, a veterinary science graduate who had tried his hand as a horse trader on the China coast.

Kelley had no time for what he described as ‘sick animal stuff’ and concentrated on improving production. Research to improve wool production by selection had been inhibited since the late 1930s by a New Zealand scientist’s erroneous findings of low heritability for fleece weight in sheep. In contrast, Helen Turner’s earliest analysis of breeding figures from Gilruth Plains showed high heritability, over 30 per cent of variation between sheep being genetic, which made it possible to select parents for wool weight and other qualities and to do away with progeny testing. These findings, backed by statistical proof, excited both great interest and controversy when they were revealed in 1951 ‘ controversy because the use of measurement in selecting sheep was new.

Helen Turner was particularly interested in the possibility of selecting for wool quality by measuring the average fibre diameter of the fleece instead of trying to estimate it from crimp ‘ the wavy configuration of fibre which graziers and the wool selling industry used in judging the quality fleeces. This emphasis on diameter anticipated the Objective Measurement revolution in wool assessment by 20 years.

Pioneering research

The research into reproduction, which was to result in Helen Turner’s pioneering twinning experiments, had a fortuitous beginning. ‘A happy accident’, she was to call it. In 1951, Kelley had sent ewes from Cunnamulla to the Division of Plant Industry’s station at Deniliquin, where they showed remarkable increase in reproduction rate. From an average 13 sets of twins to every 100 ewes they went to 50 sets. At this time geneticists generally were sceptical about the heritability of such characteristics. But regardless of what the pundits might think, the Officer-in-Charge at Deniliquin, Ron Prunster knew just two things ‘ the ewes had extraordinary lambing percentages and, in the usual course of events, they would be sent to market. He pleaded with the animal breeding scientists Do “something†with these ewes ‘ we can’t just sell them

Success at last

So the twin-bearing ewes among the group became the T (for twin) group and the single-bearing ewes the 0 group of what expanded into the notable Experiment AB9. Helen Turner, acting on not much more than a hunch, selected twin born and single-born rams from the same stock at Cunnamulla. She put 2 twin rams to 53 T ewes and 2 single rams to 53 0 ewes, and kept on selecting for high and low incidence of twins respectively in the T and 0 groups. With the 1956 lambing these matings gave striking evidence of multiple-birth heritability.

By 1958 the figures were remarkable. The original T ewes had produced 91 multiple births and the O group only 31. The first daughters of the T ewes had produced 21 multiples (including two sets of triplets) and the O daughters only 4 (all twins). ‘Geneticists around the world sat up and took notice’, said Helen Turner. But closer to home there was an even more positive response. Two brothers named Seears, of ‘Booroola’ near Cooma, wrote to CSIRO offering a Merino ram born in a set of quintuplets, all of which had survived. Helen Turner doubted that the ram could be pure Merino but drove down to Cooma and, found to her delight that it was one of a small flock the brothers had selected for multiple births, although without any selection on the ram side. She also bought 12 ‘Booroola’ ewes, born as triplets or quadruplets. Another 90 ewes were bought in 1965 when all the twinning groups moved to Armidale. In 1972 the B group from ‘Booroola’ produced an average of 210 lambs for every 100 ewes. ‘Quite fantastic for Merinos’, reported Helen Turner.

A number of rams and a few ewes from the B and T groups were sold to breeders, the rams being the first in Australia to be sold on measured performance. The B, T and O flocks, numbering now respectively 200, 200 and 100 breeding ewes, were retained as an invaluable resource for studies of reproduction processes in sheep.

This period, from 1956 until she ‘officially’ retired in 1973, was a golden period in sheep breeding research in Australia and the world. With SSY Young, AA Dunlop, CHS Dolling and others, Helen Newton Turner laid the foundations for an objective, measurement-based approach to sheep breeding, pioneering techniques that now form the basis of most sheep breeding in Australia, and have been of very great economic benefit to the country.

Post retirement activities

In 1973 she officially retired from CSIRO but immediately took up an honorary research fellowship for 12 months which was renewed annually for almost 20 years therafter. A brisk and humorous woman, she continually used to refer to her relationship with CSIRO as ‘we’ and then ruefully corrected herself, finding it difficult to accept that she was no longer a member of the staff.

Towards the end of her ‘official’ working career, she began to participate in a wide variety of overseas research and consulting activities, which took her all over the world. She has an abiding interest in the welfare of developing countries, and has devoted a considerable part of her life to overcoming their animal and food production problems. In all these activities, her input has been highly valued by each of the participating countries, and has made her a most successful ambassador of her country.

Honours and awards

Her contributions to the field of animal genetics have been recognised by election to Fellowships of numerous professional societies, including being one of two women elected as Foundation Fellows of the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences. Other awards include:

| 1987 | Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) |

| 1985 | Rotary Medal for Vocational Excellence |

| 1980 | Ceres Medal from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations |

| 1977 | Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) |

| 1974 | Farrer Memorial Medal |

| 1970 | Doctor of Science (DSc) from the University of Sydney |

| 1953 | Coronation Medal |

In 1993, the Association for the Advancement of Animal Breeding and Genetics (AAABG) established The Helen Newton Turner Medal to perpetuate her memory. The Medal is awarded by AAABG to provide encouragement and inspiration to those engaged in animal genetics.

Sources

- Andrew McKay, 1976, ‘Twinning in sheep’, In: Surprise and Enterprise ‘ Fifty Years of Science for Australia, White F, Kimpton D (eds), CSIRO Publishing, pp.36-37.

- Nessy Allen, 1995, ‘Obituary: Helen Newton Turner’, published in The Australian