Waterfowl in Australia

Harry Frith’s life spanned a period in Australian society when perceptions about native animals and plants changed from one of regarding most of them as a nuisance to be removed to one of recognising that they are a priceless heritage to be protected and cherished.

In his career as a biologist in Australia, Frith played an important role in bringing about that change in perception, through his investigations of the behaviour and ecology of many species of Australian birds and of kangaroos, through his leadership of research on wildlife in CSIRO, through the books he wrote for the general public, and through his influence on conservation policy in State and Federal Governments.

From 1951 to 1957, Harry Frith carried out the first scientific survey of waterfowl in Australia. He made observations along the Murray-Darling and their tributaries: the Ovens and Goulburn; the Lachlan and Murrumbidgee; the Macquarie and Gwydir; and the Bulloo – Paroo – Warrego systems. This period was characterised by times of near drought interspersed with flood years and his data revealed that breeding was controlled by water level. This was a remarkable observation that demanded a radical reappraisal of the accepted concepts of waterfowl conservation.

His findings led him to highlight the need for States and the Federal Government to agree on a common resource policy and involve biologists in the planning of water and wildlife conservation.

Background – were ducks destroying irrigation crops?

In 1950, Harry Frith, a keen amateur naturalist and a qualified agricultural scientist working in CSIRO on horticulture, transferred to the newly formed Wildlife Survey Section. His first brief was prompted by complaints from rice-growers in the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area that wild duck were destroying their crops. But his investigation was much wider than that, encompassing the ‘ecology and bio-economics of the wild duck’.

The basic areas of information needed were diet, breeding, movement and the factors regulating them. He was able to get approval from the New South Wales authorities to conduct year-round selective shooting. Each month he began taking a variety of waterfowl including 20 black duck and 20 grey teal, Australia’s two most important game birds, to provide a steady and unbroken stream of data. He was soon able to show that ducks were not the pest rice-growers supposed them to be and that much of the damage attributed to them was, in fact, caused by other factors.

The first scientific survey of waterfowl in Australia

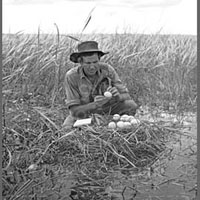

In 1953, Harry Frith sat ten metres up in a redgum tree in a swamp near Griffith, New South Wales, engaged in the first scientific survey of waterfowl in Australia. With a razor-sharp tomahawk he chopped at a limb in which a grey teal had made her nest. The limb broke – and it was then that Harry Frith decided it was not the best method of gathering breeding data, anyway. Instead he began examining the testes and ovaries of ducks shot to a regular schedule.

What he found by looking at the reproductive organs of male grey teal in the Murray-Darling area revealed evidence of remarkable adaptation to the bird’s environment and the first understanding of the species’ eccentric life cycle. His findings demanded a radical reappraisal of accepted concepts of waterfowl conservation.

Banding

In 1953, Frith began banding ducks, not just the two most common species but whatever he was able to trap. About this time the natural conditions of the Murray-Darling area, (which includes their tributaries the Ovens and Goulburn, the Lachlan and Murrumbidgee, the Macquarie and Gwydir, and the Bulloo – Paroo – Warrego systems), began to shape his observations. The flood years of 1951 and 1952 were followed by a near drought in 1954 and Frith began to see how this had had a marked effect on duck behaviour and populations.

Relationship between breeding activity and water supply

In 1955 there was a minor flood down the Lachlan river and Frith drove east of Booligal where he shot several ducks and found their testes were sexually mature. Then in the same day he drove 160 kilometres to get ahead of the floodwaters and shot several more ducks. Their testes were sexually inactive. In that moment Frith had dramatic confirmation of what he had begun to suspect: that breeding was controlled by water level. In the following two years he was blessed with good luck; floods in 1956 and then drought in 1957 provided him with further evidence of how ducks had adapted to their unpredictable environment to ensure the continuation of their species.

In 1957, Frith was making an investigation of wild geese in the new rice-growing areas near Darwin, when grey teal began arriving in thousands. Frith phoned an urgent request to his colleagues in Canberra to send traps and within a few months he and others had banded 5,000 birds. At this time there was already a well-established duck-banding program under way in southern Australia.

Over the following years as banded grey teal were shot, the recovered bands revealed an extraordinary pattern of explosive dispersal in times of drought. Driven out of the Murray-Darling breeding area by dry conditions, the teal would fly at random until they reached other water. Some might reach New Guinea and New Zealand but it was likely that many more fell into the ocean and died. Others found their haven along the east coast in the natural swamp refuges many of which are now threatened by land reclamation and real-estate development.

Recommendations for the future

Later work showed that in times of drought grey teal might not breed for several years, yet within only ten days of an increase in water level they could become sexually active and lay eggs. Harry Frith stated:

When hydroelectric and irrigation schemes finally control all floods, the grey teal and many other waterfowl will have few places left to breed.

To prevent this, the replenishment of billabongs along inland rivers must be ensured and the coastal swamp refuges protected. Most importantly, the States and the Federal Government must agree on a common resource policy and involve biologists in the planning of water conservation.

Honours and awards

He received many honours and awards for his contributions. In 1974, he became a permanent member of the Executive Committee of the International Ornithological Union and he was the Organising Secretary for the 16th International Ornithological Congress, held in Canberra.

In the mid 1970s he was successively elected to Fellowship of the Ornithological Unions of Australia, Britain, Germany, France and the United States.

In 1975, he was simultaneously elected to Fellowship of the Australian Academy of Science and the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences.

In 1980, he was appointed Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for his services to the understanding and conservation of Australian wildlife. He was nominated for this honour by the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service and he was very affected by this action and the recognition it gave to his work.

Sources

- McKay A, 1976, ‘Waterfowl and water levels’, Surprise and Enterprise, Fifty Years of Science for Australia, White F, Kimpton D (eds), CSIRO Publishing, pp.16-17.

- Tyndale-Biscoe CH, Calaby JH, Davies SJJF, 1995, Biographical memoirs: Harold James Frith 1921-1982 (Australian Academy of Science)