Pastures for the north

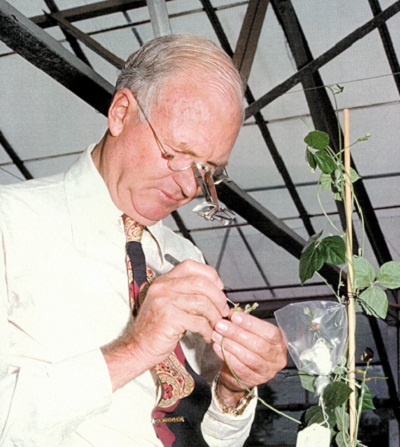

An ebullient Welshman, John (Jack) Griffiths Davies arrived in Australia wearing a bowler hat and nursing an unconcealed ambition to break new ground. He stayed to become a man of the land equal to the toughest Queensland cattleman, and has a memorial as vast as his adopted country. Those who would seek his epitaph need only look around them at the grazing lands of Australia.

With his earliest work for the Waite Agricultural Research Institute at Adelaide in the 1930s he developed a comprehensive philosophy of the ecological approach to pasture research. He saw the interacting soil-plant-animal relationship as an entity long before it was common to do so. He emphasised that sheep or cattle were not only an end product and a final measure of pasture value, but agents that conditioned the pasture. His interest in tropical legumes from South America and Africa was to be the basis of his most important and enduring work once he moved to CSIRO.

In collaboration with colleagues William Hartley, Don Norris, John Miles, Norman Shaw, Mike Norman, Wilf Bryan and Colin Andrew the carrying capacity of previously infertile, poor country was transformed. This research culminated in 1960 with the development by Mark Hutton of the new tropical legume Siratro.

Initial studies at the Waite Institute in South Australia

Griffiths Davies graduated with first-class honours in botany from the University College of Wales and completed his PhD at the Welsh Plant Breeding Station at the age of 22. Looking for a fresh challenge, he accepted a position as a pasture scientist at the Waite Institute in South Australia in 1927.

At that time scientists had looked at only limited aspects of the relationship between pastures and stock. Griffiths Davies made studies of native Danthonia (wallaby grass) pastures and their effects on wool production and weight changes in Merinos. This was the first scientific investigation of grazing management in Australia. With a Waite Institute colleague, HC Trumble, he promoted Phalaris tuberosa, an imported perennial grass which has become one of the major pasture species of south-eastern Australia.

Griffiths Davies’ research style

His comprehensive, over-view approach to his work began to change him from a research scientist to a research director. He developed a method of attack which he was to use for the rest of his career:

- define the problem

- provide the necessary facilities in the field and the laboratory

- call in the specialists to use them.

This way he could do what he was best at ‘ plan and lead. He was one of the first to plan pasture experiments under statistical controls and to use mathematicians to help him in their evaluation. His success in leadership came from an intense belief in loyalty, an ability to infect others with his conviction and enthusiasm, and sound basic psychology in ensuring his team always received full credit for their work.

The beginning of tropical pasture research in CSIRO

Griffiths Davies was appointed as the first head of pasture research for the CSIRO Division of Plant Industry in 1938. In the following two years he made two wide-ranging tours through Queensland cattle country, driving to remote stations to yarn with graziers about their problems. These tours and a brief paper published in 1935 by William Hartley, the Division’s Assistant Plant Introduction Officer, probably had most effect on his future thinking about tropical pasture legumes.

The history of pasture research in northern Australia has been dominated by a search for such legumes ‘ legumes that would play the same role in pasture improvement as clovers and medics had played in the cooler climates. Legumes are extremely valuable as they have the ability to fix nitrogen (that is to obtain the nitrogen they need for their nutrition from the air) via special bacteria which live in nodules in their roots. Since no country in the tropics had developed systems of animal husbandry based on grass/legume pastures, there were no ready-made tropical pasture legumes that could be imported. The first step was to find ‘wild’ legumes that could be ‘domesticated’. In his paper William Hartley emphasised the potential value of tropical legumes and noted that:

The most fertile hunting ground for promising species appears to be the extensive area from Brazil to northern Argentina, which has a climate and vegetation similar to much of tropical Australia.

By 1952, when Griffiths Davies moved to Brisbane, he had built his Pasture Section into the biggest Section in the Division of Plant Industry. In Brisbane he took charge of a small group of scientists he had already established there and began adding to their numbers and objectives. Eventually this group expanded into the new Division of Tropical Pastures.

The right mix of legume, nitrogen-fixing bacteria and soil trace elements

One of the team, Don Norris, stressed the advantage of tropical legumes being adapted to acid, infertile, tropical soils. He attributed this adaptation to their having evolved during long periods of growth in such soils. His practical contribution was to provide the right kinds of nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Some of these strains of bacteria had to be imported together with their host legumes.

This came at a time when there was a fresh search overseas for promising tropical legumes. The Plant Introduction Section had been importing them since 1930 and botanist John Miles had grown a number of promising species at Fitzroyvale, near Rockhampton in Queensland, but without the facilities for putting them into grazing trials.

In 1945 scientist Norman Shaw enlisted the cooperation of his brother Desmond who had been growing the tropical legume Townsville stylo on his property at Rodd’s Bay, near Gladstone, since 1937. (This legume had been accidentally introduced into Australia from South America about 1900 and exploited by only a very few enterprising cattlemen and agricultural advisers.) The Shaw brothers’ experiments with Townsville stylo and fertilisers for pasture improvement at Rodd’s Bay led to the realisation that it could provide pasture in country stretching from Bundaberg to north Queensland. Proof of its value in the Northern Territory came from research done by Mike Norman, of the CSIRO Division of Land Research at Katherine. In subtropical areas it became possible to run a beast to less than a hectare instead of four hectares. In the north, stocking could be increased dramatically from a beast every 12 hectares to one every hectare.

Next came the work by agronomist Wilf Bryan and nutritionist Col Andrew on the Queensland coastal Wallum country, some of the most infertile soil in the world. Stretching from just north of Brisbane to Bundaberg, the Wallum region was unable to support cattle permanently. While Col Andrew tracked down missing soil elements, Wilf Bryan tested new foreign legumes. With the addition of a formidable combination of trace elements, plus superphosphate and potash, imported pastures thrived. Legumes like lotononis and Greenleaf desmodium from South America, combined with grasses from Africa, made it possible to carry a bullock, year-round, on less than half a hectare. This was the highest carrying capacity of any legume pasture in Queensland.

The development of Siratro

In the mid 1950s Mark Hutton investigated the possibility of breeding an improved pasture legume from the genus Phaseolus (now Macroptilium). Having seen how phasey bean, a biennial in the same genus, grew successfully in southern Queensland, Hutton crossed two perennial Macroptilium strains from Mexico and after selection under grazing produced the new legume, Siratro, in 1960. From southern Oueensland to Townsville, Siratro helped cattlemen fatten cattle at a stocking rate of one beast per hectare in 27 months, instead of the previous rate of one beast per three hectares over four years. Siratro seed became a valuable export.

Source

- McKay A, 1976, ‘Pastures for the north’, In: Surprise and Enterprise, Fifty Years of Science for Australia, White F, Kimpton D (eds), CSIRO Publishing, pp.26-27.