Michael George Pitman [1933-2000]

Biography

Michael George Pitman, the eldest of three boys, was born on 7 February 1933 at the family home in Clift Street, Ashton UK. The Pitmans were a prolific West England family with Sir Isaac Pitman, the inventor of shorthand the most famous member. During the 1800s, four members of different branches of the family emigrated to Australia, but Michael’s branch remained in Bristol. Michael’s grandfather, George worked first as a draper but later established his own pork butcher’s shop at the other end of Bedminster. In time he was joined by Michael’s father. Michael’s mother, Norma Ethel Payne, was trained and worked as a milliner. When Michael was five, the Pitman family business became bankrupt and the family lived for a while with Mrs Pitman’s family at Ashton. Michael’s father became a buyer at the Bristol Aeroplane Company.

Michael started his education at Southville Primary School in a suburb adjacent to Bedminster. When World War II started, the inner city area of Bristol was heavily bombed and Bedminster, Southville and Ashton were pummelled. It was decided that Mrs Pitman and the two boys should go to the relative safety of the Somerset village of East Harptree, situated on the northern slopes of the Mendip hills, south of Bristol. Michael attended the village school for about a year. When the family returned to Bristol they settled on the southern outskirts in the suburb of Bishopsworth and the two boys commuted daily to the Southville School. Michael, at nine years of age, was in sole charge of his brother on this journey, as his mother was fully occupied with the new baby who suffered from the disability of Downes Syndrome. Michael’s memories of these times were those of a loving family and the freedom to roam the fields and explore, both in East Harptree and Bishopsworth.

Michael’s grandfather and father both attended the Colston’s School at Stapleton, Bristol. This was a boys’ boarding school founded by the Merchant Venturer, Sir Edward Colston in 1708. Financial circumstances were such that Michael’s only hope of keeping up the family tradition was through scholarships. Michael was successful in winning one of the school’s foundation scholarships which covered some of the fees and also a County scholarship which made up the remainder. He started as a boarder in September 1944 at the age of eleven.

Life at Colston’s school was rather Spartan with four very large unheated dormitories, cold water in the adjacent washrooms, food and fuel rationing and no half-term break. Despite these restrictions Michael seemed to get the most out of the school. In his last two years at school he won the science prize, the mathematics problem prize and the English essay prize, the latter being a remarkable achievement because his school reports indicated that he had quite a struggle with English. Michael won a State Scholarship and a Cambridge Open Scholarship to Sidney Sussex College. These made it possible for him to go to Cambridge University in 1952.

Michael’s schooling and undergraduate days took place in postwar Britain, which he found to be a very exciting time because people were rediscovering or reaffirming visions about society, welfare, equity and humanity. He obtained a First-Class BSc degree from Cambridge and gained an Agricultural Research Council Research Scholarship which enabled him to do a PhD in the Botany Department at Cambridge under the supervision of the eminent plant physiologist, Professor GE Briggs. He completed his PhD in 1959 and then did postdoctoral research and teaching in the Botany Department as a junior Fellow at St John’s College.

In 1962, he was appointed to a position of Lecturer at Adelaide University and with it came the opportunity to interact with Professor Bob (later Sir Rutherford) Robertson. He was eager to see the rich diversity of Australian plants and particularly to visit the arid areas where water control was so important for plants. South Australia, under the Playford Government, was very conservative at that time but there were signs of the political upheaval to come and he enjoyed the thrill of being close to political change.

He had intended the Adelaide position to be an interesting experience in a predominantly English career. Instead, it was the start of the process of ‘Australianisation’ for the family. Michael saw that the family culture was more open than in Cambridge, children were welcome at social events and there was easy mixing with people from faculties other than science. Australia was a vigorous and exciting place to be. Bob Robertson encouraged Michael to ‘throw his hat in the ring’ for the Biology Chair at Sydney University and when he took up that position in 1966, at the age of thirty-three, it was only a matter of time before the family took up Australian citizenship. He was Professor of Biology (Plant Physiology), University of Sydney for 17 years (1966-83).

Scientific contributions

Michael Pitman’s research focused on plant nutrition where he aimed to improve understanding of the functions of parts in the whole. He sought to integrate the ionic relations of cell compartments, determined by the interactions of fluxes of sodium and potassium at membranes, into those of the root and whole plant. Through his success, Michael contributed massively to establishing the international reputation of this sector of research in Australian plant science in the 1970s. It soon made him one of the foremost exponents of modern whole-plant-physiology.

Recruited to Adelaide by Bob Robertson in 1962, Michael inspired a generation of research students through his simple, elegant experiments and clear formal analysis. Bob Robertson passed the baton in plant ion transport to a new generation and he was pleased to have passed it to Michael Pitman. Barry Osmond recalls how large refrigerated tubs, still decorated with the trade marks of the Coca Cola Company, were pressed into service as temperature control devices, and remembers Michael working frenetically with lead chambers and decade-counting tubes to extract data from fast decaying isotopes. In establishing the ‘three compartments in series’ model of ionic relations in higher plant cells, Michael brought contemporary rigour to a controversial field in which his personal friendships, as much as his science, were instrumental in overcoming controversy and in generating new concepts.

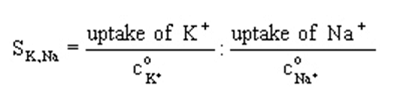

He found an immediate practical application of compartmental analysis soon after his arrival in Adelaide; the problem of plant growth under salinity. In a particularly fruitful partnership with Hank Greenway the fluxes, permeabilities (PNa+/PK+-ratios) and pools were analysed and the simple well-known selectivity factor ‘SK, Na‘ emerged (where c° designates external concentrations).

Salinity as a paramount problem in plant physiology and agriculture was never far from the centre of Michael’s attention. Sydneysiders will not forget how Pitman’s group discovered that detergents in the sewage outfall conveyed killer salt spray through the stomates of otherwise wax-protected leaves of Norfolk Island pines, removing many of these landmarks from the northern beaches in the course of a few years. This work was a good example of Michael’s ability to fuse elegant experimental biology with issues of community concern.

Other contributions included the development of the two pump hypothesis for ion transport in plant roots; water transport and hydraulic conductivity of roots and the identification of the two strategies for salinity tolerance in mangroves in the field. In the last example the identification of one mangrove species as a salt includer at the root level with salt glands in its leaves, and another identified as a salt excluder at the root and lacked leaf salt glands was a masterpiece of whole plant physiology.

He followed up this interest on several research visits to One Tree Island in the Great Barrier Reef, where he and a diverse group of colleagues explored relationships between water potential and sap flow, and osmotic relationships, in plants growing in this strange environment.

In this atmosphere of scientific excitement and the mood of collaborative achievements, attributed by Michael to the ‘group effect’, the prospect emerged to collect the entire current knowledge on transport in plants, at the levels of cells, tissues and organs, in a multi-author volume. This was realised in collaboration with Ulrich Lüttge as co-editor of volumes 2A and 2B in Springer’s Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology, New Series. The Encyclopedia volumes were a crowning achievement and testimony to Michael’s work as an active, creative researcher, communicator and exponent of scientific ideas understanding.

Contributions to education and the community

In the 1960s and 1970s, Michael played a key role in the development and compilation of successive additions of The Web of Life, a school textbook sponsored by the Australian Academy of Science that elevated the teaching of biology throughout Australia. Michael regarded his involvement with The Web of Life as possibly his most important contribution to science in Australia.

Michael’s contributions to the wider community included his involvements with the Royal Botanic Gardens and the Australian Museum. He was President of the Australian Museum Trust from 1975 to 1978 and Chairman of the Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust from 1982 to 1984 during an important period when notable progress was made in advancing public interest in the Botanic Gardens. Perhaps one of Michael’s clearest legacies to Sydneysiders is the gradual re-establishment of Norfolk Island Pines on Bondi and other beachfronts, together with the clean water for swimming, which followed many years of upgrading of sewage treatment following his researches mentioned earlier on the cause of die-back of the Norfolk Island Pines.

In addition to these community activities and his busy teaching and creative research, Michael served as a member of the Australian Research Grants Committee (1975-78), the Australian Science and Technology Council (1982-83), the Council of the Australian Institute of Marine Science (1978-84), and the Australian Biological Resources Advisory Committee (1983-86).

At CSIRO

Institute Director

In 1983, he left his Chair of Plant Physiology at the University of Sydney to become Director of the CSIRO Institute of Biological Resources. The Institute with eight divisions was responsible for performing plant and environmental R&D with the objective of improving agricultural and forestry production and the management of the natural environment, including land and water resources.

He was an Associate Member of the CSIRO Executive in 1985 and 1986 and became Deputy to the Chief Executive, Dr Keith Boardman in 1986. As Associate Member of the Executive, he assumed overall responsibility at the corporate level for interaction with CSIRO’s major customers in the rural and environment sectors. As Chairman of the CSIRO Advisory Committee on Ethics in Animal Research, Michael proved to be particularly effective in reducing the conflict between the representatives of animal welfare groups and those of animal researchers in CSIRO.

As Deputy to the Chief Executive, Michael had responsibility for a range of activities but with a particular role for human resources policies and interaction with the Staff Associations. He foresaw the need for a new approach to the management of human resources in CSIRO at a time of diminishing resources from Government. Many of the changes that were implemented owe their evolution to his initiatives.

Chief Scientific Advisor

In 1988, at the request of the Minister for Science, the Hon Barry Jones, CSIRO seconded Michael to the Department of Industry, Technology and Commerce as Chief Scientific Advisor and as the Minister’s Personal Advisor. Michael played a crucial role in ensuring that research and development and science awareness were recognised as components in policy development in the Department. Working with the Minister, Michael made a significant contribution to the Prime Minister’s Science and Technology Statement of May 1989 that included the commitment to establish a Prime Minister’s Science Council and a Cooperative Research Centres Program and provide additional resources for research in Government agencies and the universities. The Minister expressed his debt to Michael in a personal letter of 10 May, 1989:

Your contribution to the S&T Statement was inestimable. You have done very well in helping to shift the thinking within DITAC, indeed your role has been central to affecting a cultural shift that will be of lasting importance.

Chief Scientist of Australia

From 1992 to 1996, Michael was Chief Scientist of Australia. The responsibilities of the Chief Scientist included the provision of advice to the Prime Minister and the Minister assisting the Prime Minister on Science on the overall contribution of science, technology and engineering to the standard and quality of life in Australia and the ‘health’ of the science system. As Chief Scientist, Michael was Executive Officer of the Prime Minister’s Science and Engineering Council, Chair of the Co-ordination Committee on Science and Technology that consisted of the Deputy Secretaries of Departments with significant science components and Chair of the Cooperative Research Centres (CRC) Committee. Michael was not a supporter of a centralist approach in Government to science and technology and he saw his role as largely one of coordination. He also saw a role for the Chief Scientist in improving science awareness in the community as well as in Government and industry.

As Chair of the CRC Committee, Michael oversaw the expansion and development of the CRC Program to become a substantial and important component of R&D in Australia. There was increasing involvement of industry and other users as partners in CRCs. Michael was a keen supporter of schemes which promoted linkages between scientists and he promoted the advantages of dialogue between fundamental science and mission-oriented granting schemes.

Following his retirement as Chief Scientist, Michael continued to contribute to the CRC Program as Visitor to the CRC for Ecologically Sustainable Development of the Great Barrier Reef and the CRC for Sustainable Tourism.

Australian Academy of Science committees

In 1997, Michael was elected Foreign Secretary of the Australian Academy of Science. This enabled him to continue to make an important contribution to the advancement of Australian international relationships in science and increased coordination of international S&T activities. The Academy’s role in Australia’s international collaborations in science was expanded when the Academy took over the administration of elements of the International S&T Program of the Department of Industry, Science and Resources. He improved rapport with several countries of South-East Asia as well as promoting closer collaboration with Europe, particularly France. Michael resigned as Foreign Secretary in 1999 due to illness and died in Canberra on 30 March 2000.

Honours and awards

In recognition of his very significant contributions over several years to improving French-Australian relationships in science, the French Government awarded Michael the Chevalier de l’Ordre national du Mérite. Other honours and awards include:

Fellowships

| 1997 | Fellow, Australian Institute of Agricultural Science and Technology |

| 1981 | Fellow, Australian Academy of Science |

Awards

| 1979 | Doctor of Science, Cambridge University, UK |

| 1978 | Officer of the British Empire (OBE) |

A full account of the life and achievements of Michael Pitman can be found by following the link in the Source details below.

Source

- Boardman NK, Osmond B, Lüttge. U, 2002, Biographical memoirs: Michael George Pitman 1933-2000 (Australian Academy of Science)