Pulsars make a GPS for the cosmos

Dr George Hobbs (CSIRO) and his colleagues study pulsars — small spinning stars that deliver regular ‘blips’ or ‘pulses’ of radio waves and, sometimes, X-rays.

Usually the astronomers are interested in measuring, very precisely, when the pulsar pulses arrive in the solar system. Slight deviations from the expected arrival times can give clues about the behaviour of a pulsar itself, or whether it is orbiting another star, for instance.

“But we can also work backwards,” said Dr Hobbs. “We can use information from pulsars to very precisely determine the position of our telescopes.”

“If the telescopes were on board a spacecraft, then we could get the position of the spacecraft.”

Observations of at least four pulsars, every seven days, would be required. “Each pulsar would have to be observed for about an hour,” Dr Hobbs said. “Whether you can do them all at the same time or have to do them one after the other depends on where they are and exactly what kind of detector you use.”

A paper describing in detail how the system would work has been accepted for publication by the journal Advances in Space Research.

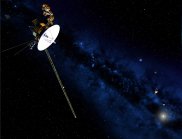

Spacecraft within the solar system are usually tracked and guided from the ground: this is the role of CSIRO’s Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex, for instance. But the further out the craft go, the less accurately we can measure their locations.

For voyages beyond the solar system, spacecraft would need an on-board (‘autonomous’) system for navigation. Gyroscopes and accelerometers are useful tools, but the position information they give becomes less accurate over time.

“Navigating with pulsars avoids these problems,” said Deng Xinping, PhD student at the National Space Science Center in Beijing, who is first author on the paper describing the system.

“This is the best accuracy anyone has ever been able to demonstrate”

Dr George Hobbs

Scientists proposed pulsar navigation as early as 1974. Putting it into practice has recently come closer, with the development of fairly small, lightweight X-ray detectors that could receive the X-ray pulses that certain pulsars emit. NASA is exploring the technique.

“For deep-space navigation, we would use pulsars that had been observed for many years with radio telescopes such as Parkes, so that the timing of their pulses is very well measured,” said CSIRO’s Dr Dick Manchester, a member of the research team. “Then on board the spacecraft you’d use an X-ray telescope, which is much smaller and lighter.”

Dr Hobbs and his colleagues have made a very detailed simulation of a spacecraft navigating autonomously to Mars using this combination of technologies and their TEMPO2 software.

“The spacecraft can determine its position to within about 20 km, and its velocity to within 10 cm per second,” said Dr Hobbs. “To our knowledge, this is the best accuracy anyone has ever been able to demonstrate.”

“Unlike previous work, we’ve taken into account that real pulsars are not quite perfect, they have timing glitches and so on. We’ve allowed for that.”

The same pulsar software can be used to work out the masses of objects in the solar system.

In 2010 Dr Hobbs and his colleagues used an earlier version of the software to ‘weigh’ the planets out as far as Saturn — to six decimal places.

The Earth is travelling around the Sun, and this movement affects exactly when pulsar signals arrive here. To remove this effect, astronomers calculate when the pulses would have arrived at the Solar System’s centre of mass, around which all the planets orbit.

“If the pulsar signals appear to be coming in at the wrong time, we know that the masses of the planets that we are using in the equations must be wrong, and we can correct for this,” Dr Hobbs explained.

The new version of the software lets the astronomers rule out unseen masses, including any supposedly undiscovered planets, such as the notorious Nibiru.

“Even if a planet is hard to see, there’s no way to disguise its gravitational pull,” Dr Hobbs said. “If we don’t detect the gravitational pull, then there’s no planet there. Full stop.”

And what about showing that the Earth goes around the Sun? Yes, they can do that too.

“This was nailed a couple of hundred years ago,” said Dr Hobbs. “But if you still need proof, we’ve got it.”