The oil-free vacuum pump for sophisticated instruments and industries

The need for a vacuum pump that did not contaminate the system being evacuated with residual oil vapour had long been felt by the users of scientific instruments such as electron microscopes, and more recently in the semi-conductor and coating industries. In the early 1970s John Farrant, of the CSIRO Division of Chemical Physics, considered means by which a reciprocating oil-free pump could be constructed, and such a pump was built in the Division.

In 1977 the Australian firm Repco Ltd was licensed to develop and market this pump but two years later withdrew from the project. In 1983, after further developmental work at Chemical Physics, the American firm Varian was licensed to go ahead with the commercial production of the pump, with great success. The Varian pumps operated at 1 200 rpm and a stroke of 2.5 cm meaning that in a year each piston travelled 31 000 km. In addition the valves, their springs and their associated dry seals had to meet stringent demands in performance and longevity. They opened and sealed 1 200 times per minute, for lifetimes of well over 10 000 hrs, operating dry for well over 720 million cycles, yet running cooler than conventional oil-lubricated pumps.

The pumps were well received in many applications including the semi-conductor industry and uranium isotope enrichment. Varian later sold its licence to the Vacuum Research Corporation (VRC), Pittsburgh. A non-exclusive licence to manufacture the pumps was also granted to the Japanese company, Fujei Seiki.

The CSIRO Division of Chemical Physics and the Australian scientific instrument industry

The Australian Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), which in 1949 became the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), set up a Division of Industrial Chemistry in 1940, with Dr (later Sir) Ian Wark as Chief. In 1944 Wark appointed Dr ALG Rees to form a Chemical Physics Section in that Division. In 1958 the Chemical Physics Section became the Division of Chemical Physics.

Rees always had the ambition that Chemical Physics should encourage the development of an Australian scientific instrument industry, and the first major success in this field was the manufacture by an Australian firm, Techtron Pty Ltd, of the atomic absorption spectrometer, which had been invented by Dr (later Sir) Alan Walsh and developed in the Division. In 1967 Techtron was acquired by the American firm of Varian Associates, but continued to manufacture spectrometers in Australia, and close contact was maintained between the Division of Chemical Physics and Varian Techtron Pty Ltd (from 1991 known as Varian Australia Pty Ltd).

One of the functions of the Chemical Physics Section was to introduce new physical techniques which could be applied to the solution of chemical problems; these included electron microscopy, electron diffraction, and mass spectrometry. It imported the first electron microscope in Australia, built by the Radio Corporation of America, and John L Farrant was appointed to install and operate it. Farrant and his colleagues began to work on problems such as the structure of wool fibres, the work being extended to other fibrous proteins as well as to viruses, muscle tissue, the structure of ferritin and so on. They modified the RCA instrument to give higher resolution, and soon came to appreciate the problems of oil contamination of the specimen.

The need for an oil-free vacuum pump

Many modern scientific instruments, such as electron microscopes and electron diffraction cameras, and more recently installations used in the semiconductor and coating industries, operate in a high vacuum, which must be completely free from contaminants such as traces of oil.

For more than 100 years the basic workhorse in vacuum technology has been the rotary-vane type of oil-sealed pump introduced by Wolfgang Gaede in 1905. This type of pump provided the means of attaining the medium vacuum levels required as backing for oil diffusion pumps, sorption pumps, ion pumps, turbo-molecular pumps and cryopumps.

While the rotary pump has undergone many improvements over the years, one of its intrinsic features has become progressively more detrimental to many of its uses. As the technology of post-Second World War years demanded higher levels of vacuum and cleaner vacuum conditions, the oil bath which the rotary motion requires for satisfactory operation has increasingly been identified as the source of a serious defect, namely the gaseous hydrocarbon breakdown products of the oil as well as the oil vapour itself. Many attempts have been made to achieve an alternative method of generating a backing vacuum without involving oil. None of these attempts proved really successful in terms of practical utility in continuously providing vacuum of around 1 Pa.

In the electron microscope, material originating from the oil vapour, degraded by the electron beam, showed up as a carbon coating on the specimen and the aperture diaphragms, obscuring the finer details and adversely affecting the optical performance of the microscope.

The birth of the oil-free vacuum pump

Experiments with a glass hypodermic syringe with a glass plunger suggested to Farrant that a dry-contact piston pump was possible, though clearly glass would not be a suitable material for its construction.

About 1968 Farrant heard that ways had been found of greatly increasing the wear resistance of Teflon, the material that is used to line cooking vessels. It is a very inert substance and has a very low coefficient of friction, but it seemed impossible to construct a pump using a Teflon coating on the piston because Teflon is so soft. However, a method had been found of increasing the wear-resistance by about 1 000-fold by incorporating into it graphite, glass fibre, molybdenum disulphide, various carbon blacks, and even bronze powder.

With the help of Eckhard Bez and Karl Balkau, both skilled instrument makers, Farrant developed a prototype of a reciprocating pump with piston rings made of Teflon. Bez had served his apprenticeship as an instrument maker in the Division’s workshop and was Victorian Apprentice of the Year in 1964; Balkau had had a rigorous training as an instrument maker in pre-war Germany.

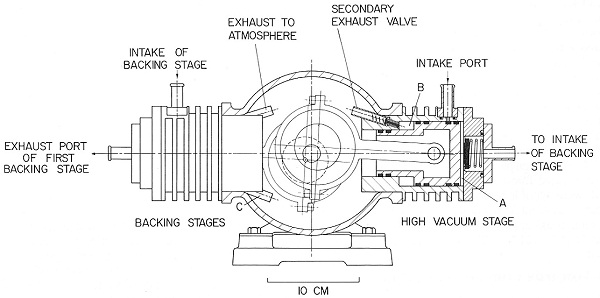

The first really successful model, shown in diagrammatic form in the figure below, involved two horizontally-opposed cylinders to simplify balancing: these operated in series, one providing the backing stage and the other the high-vacuum stage. The stepped pistons divided each cylinder into an annular working space and a cylindrical working place. The mean pressures in the annular working spaces were low, so leakage of air into the high-vacuum cylindrical working spaces was insignificant. This model, tested in 1974, ran at 635 rpm and the ultimate pressure achieved was 0.080 Torr (~10 Pa). After 1 000 hours running, the wear on the piston rings was too small to markedly affect performance and the wear on the cylinder walls was scarcely detectable.

Laboratory development

To improve both the ultimate vacuum and also the pumping speed, various features of the design had to be assessed, and this led to numerous modifications. The principal difficulties encountered arose from the high thermal expansion and low thermal conductivity of all filled-teflon materials. Numerous types of piston ring were designed and tried before piston seals of sufficient durability were devised. Later versions of the pump incorporated parallel twin cylinders, again operating in series, but ultimately a 90º V four-cylinder configuration was adopted.

An Australian-made oil-free pump?

In 1972 an Australian patent on the oil-free pump was applied for in the names of Bez and Farrant, and the patent (No. 481072) was granted in 1977. Patents were later taken out in various overseas countries. A license to manufacture was granted to Scientific Glass Engineering Pty Ltd, a Melbourne-based company which specialised in manufacturing components for gas and liquid chromatographs, but little or no work appears to have been done on the pump by this company.

In 1977 CSIRO advertised for an Australian manufacturer to undertake the development and production of the oil-free vacuum pump. The successful applicant was Repco Ltd, a large Australian engineering company primarily concerned with the manufacture of components for the automotive industry. It possessed expertise in reciprocating piston machines but not in vacuum technology. Steps were taken to estimate the size of the possible market for an oil-free vacuum pump, a license was issued to Repco, and collaboration on development was begun.

In 1978 Farrant travelled overseas and visited a number of firms such as Varian and Perkin-Elmer in the USA, and Leybold and Balzer in Europe, seeking information from them concerning the marketability of an oil-free pump. He found general scepticism except at the German firm of Leybold, which sent its director of research, Hansen Pfaff, to Australia to investigate the situation. It was explained to him that CSIRO had an obligation to license an Australian firm if at all possible, and he was taken to visit Repco. He agreed that Repco had the ability to manufacture the pump but said that since the company was unknown in the vacuum world it would have difficulty in marketing it. He offered Repco a deal, in which Leybold would offer Repco technical help in return for an exclusive marketing license. Repco accepted the offer and sent a pump to Germany for evaluation. Leybold performed extensive tests and reported that the pump should be developed further by overcoming certain difficulties and improving the speed of pumping at low pressures.

The Australian company pulls out while a German company shows interest

However, at the end of 1979 Repco decided that it would do better to concentrate on the automotive parts industry rather than be involved in things that were outside its area of expertise, and gave up its license to produce the oil-free pump. As John Willis recalled:

I recall vividly the day just before Christmas 1979, when as Assistant Chief I was present when Sandy Mathieson, the Acting Chief, received the message that Repco had given up its involvement in the pump. It was a most unwelcome Christmas present for the Division, and particularly for Mathieson, who had always strongly supported the project.

Undeterred Farrant took a pump to Leybold for a second assessment in 1980. Leybold, however, was having a difficult time financially and had had to reduce some of its own activities. Nevertheless it was still enthusiastic that the development of the oil-free pump should continue and wanted a marketing license if the pump could be manufactured elsewhere. It was agreed that Varian would be a good company to develop the pump, and collaboration with this company seemed promising because of the excellent relations that the Division of Chemical Physics had established with Varian Australia over the manufacture of the atomic absorption spectrometer.

Varian undertakes to manufacture the pump

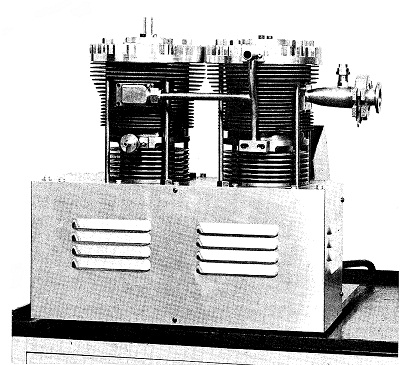

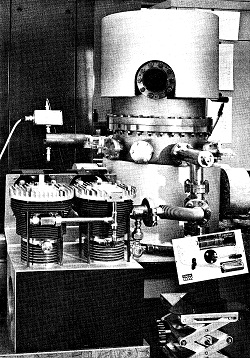

In early 1981 Farrant approached the division of Varian in Lexington, Massachusetts, where most of its pump-making and vacuum activities were carried out. It was arranged that he should take two pumps to be tested at the Varian Industrial Products Division in Santa Clara, California, which he did. After running the pumps for two months Varian decided to apply for a license to manufacture; this was granted in early 1983. Farrant and Bez went to the USA to advise Varian on the construction of the first units, and the launch of the oil-free pump was announced at an International Vacuum Conference at Baltimore in 1986. The figure in the right hand panel of the Summary (above) shows the first commercial model, the Varian Dry Vacuum Pump, DVP-500.

At Santa Clara, Varian was in the heart of the semi-conductor industry, and market surveys for the pump had been conducted among customers there. The pumps sold slowly at first but met with a good reception in the semi-conductor industry, and many other industries also found them useful. The Lawrence Livermore Laboratory was one of the biggest customers: it used pumps in laser-operated systems for separating the 235 and 238 isotopes of uranium. By fitting twelve oil-free vacuum pumps to one plant it was able, for an expenditure of $100 000, to increase the value of the isotope produced by a million dollars. This laboratory bought about 100 of the pumps.

Other companies make the pump

Varian ultimately divested itself of most of its pump-manufacturing activities in the USA, and sold its CSIRO license to a small Pittsburgh company called Vacuum Research Corporation (VRC). A Japanese company, Fujei Seiki, which had been involved with VRC, was also able to obtain a license from CSIRO to manufacture oil-free pumps because VRC gave up its exclusive license in favour of a non-exclusive one.

Farrant’s own words on the pump

At the 40th Symposium of the American Vacuum Society, held at Orlando, Florida in November 1993, Farrant was interviewed by Bruce Kendall. The full text of the interview can be found by following the link in the Sources below. A few extracts from it are as follows:

In 1949 CSIRO sent me on a year-long mission. I had a roving commission to go anywhere in the world where I could learn about electron microscopes … so naturally the first place I went to was the USA, and then off to Princeton. RCA’s laboratory is in Princeton. James Hillier and his colleagues … were still hard at work trying to perfect the microscope … Hillier had investigated the sources of this contamination, and one of the things he pointed out to me was that the oil in the backing pump was a major source of the contamination because the backing pump was used to rough the microscope and to dry out the photographic plates, so that it ran quite some time before one switched on the electron beam. And during that interval, oil from the backing pump contaminated the low-vapor-pressure oil in the diffusion pump, which promptly boiled that low-vapor-pressure fraction into the column of the microscope, so that all the surfaces were covered in a thin layer … After talking to Hillier it seemed to me that absolutely oil-free pumps were needed.

It was not until 1968 that I heard that ways had been found by greatly increasing the wear resistance of Teflon … the coefficient of friction is of the order of 0.1, whereas all other substances in a dry condition exhibit much higher coefficients of friction …

Balkau and Bez must have made at least 200 different styles of piston ring and seal …

We had numerous critics in the Division and elsewhere. They all maintained that it was crazy to try to compete with an oil-lubricated machine with a dry machine. And they all predicted that they’d run very hot, that they’d have a very short life, but it turned out they were all wrong … I went overseas in 1978 and visited Perkin-Elmer, Leybold and Balzers, trying to seek information from them on the marketability of an oil-free pump. I even went to Japan to electron microscope companies. I found general scepticism everywhere, except at Leybold, where the director of research, Hansen Pfaff, to my utter surprise said ‘I think I ought to go to Australia and see this for myself’.

Some features of the oil-free vacuum pump

In their 1988 paper Clive Coogan and Sandy Mathieson (see Sources below) point out that the magnitude of the task involved in producing an oil-free vacuum pump of really competitive importance is indicated by the following requirements:

- A compression ratio of at least 50 000:1. This despite the fact that small amounts of air will inevitably leak past dry piston seals and that the unswept clearance spaces must be tolerated rather than filled with oil. Some individual pumps have reached compression ratios of well over 100 000:1.

- The piston seals are able to sustain pressure differentials of more than ± 1 atmosphere and endure at least 10 000 hours of operation over a considerable temperature range without developing intolerable leakage rates. The Varian pumps operate at 1 200 rpm and a stroke of 2.5 cm meaning that in one year’s continuous operation each piston travels 31 000 km. A Varian test pump was operated for two years without its seals requiring replacement through wear.

- The valves and their associated dry seals must meet stringent demands in performance and longevity. They must seal adequately at every stroke and operate quietly and reliably for at least 10 000 hrs without lubrication and the valve springs must withstand exposure to corrosive gases. The CSIRO design adopted internally-operated valves to avoid the tappet noise and sealing complications involved with externally operated valves. At Varian the same principles were followed and a design was developed which enabled the valves to open and seal 1 200 times per minute, for lifetimes of well over 10 000 hrs; i.e. the valves, their springs and their seals operate dry for well over 720 million cycles.

In spite of the fact that the pistons operate dry, the pumps run cooler than do conventional oil-lubricated pumps.

Sources

- Willis JB, 2011, Personal communication.

- Kendall B, 1993, Oral History Interview with John L. Farrant, American Vacuum Society ‘ Science and Technology of Materials, Interfaces and Processing.

- Coogan CK, Mathieson A McL, 1988, ‘The Invention of the CSIRO Oil-Free Vacuum Pump’, Australian Physicist, 25: 156-160.

- Vacuum Science & Technology Timeline [PDF 1.96 MB]

- Buie J, 2010, Evolution Of The Laboratory Vacuum Pump, Lab Manager Magazine.

- Redhead PA, 1994, Oil-free reciprocating piston fore-vacuum pump – 1974, Vacuum science and technology: pioneers of the 20th century, pp.93-94.