Black disease vaccine for sheep

Black disease, or infectious necrotic hepatitis, is a fatal toxaemia of sheep. In 1930, it was considered to be the most serious infectious disease affecting sheep in Australia, responsible for an annual loss to industry of £1 million in New South Wales alone, and corresponding losses in Victoria and Tasmania.

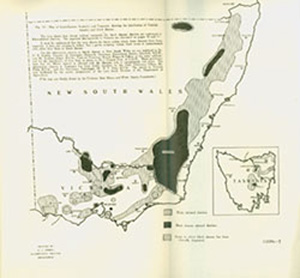

In the period 1928-30, CSIR scientists, led by Arthur Turner, began a systematic study of the natural history of black disease that culminated in the development of an effective vaccine. They established that the disease was caused by a bacterial infection following injury to the liver by young liver fluke. The initial vaccine was produced by Turner and supplied free of charge by CSIR to sheep breeders throughout Australia in 1930. After that, the vaccine was produced by the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories, and was used throughout Australia and other parts of the world to control black disease. Farmers in Victoria who used the vaccine in the early 1930s found the death rate from black-disease was reduced from 8 per cent to 0.14 per cent.

Arthur Turner received several honours and awards for his contributions including an OBE in 1938, Fellowship of the Australian Academy of Science in 1954, the Syme Prize from the University of Melbourne in 1932 and the Gilruth Prize of the Australian Veterinary Association in 1958. He was a Life Member of the Australian Veterinary Association and a Foundation Life Fellow of the Australian College of Veterinary Scientists.

The nature of the disease

Black disease, or infectious necrotic hepatitis, is a fatal toxaemia of sheep which was recorded in Australia as early as 1894. It may also occur in cattle, pigs and horses. Early investigators confused the disease in Australia with braxy, a similar disease known to occur in sheep in Scotland but caused by a different bacterium. Hence in the early Australian literature, it is called ‘braxy-like black disease’. In 1930, black disease was considered to be the most serious infectious disease affecting sheep in Australia and was costing the sheep industry about three million pounds sterling each year.

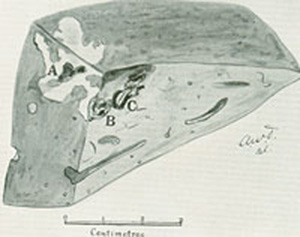

Fresh from his overseas experience, Arthur W Turner began a systematic study of the natural history of the disease that was designed ultimately to control its effect on the sheep industry of Australia. It was known that infection of sheep with the liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica) was often seen in cases of black disease. It was also known that the spores of the bacterium B. oedematiens could sometimes be found in the liver of sheep that showed no clinical signs of black disease. Turner, by a series of careful and detailed experiments, demonstrated that, when the liver of a sheep is invaded by the wandering larvae of the liver fluke on its way through the liver tissue to a bile duct, the invaded tissue is damaged to such an extent that the oxygen tension of the tissue is lowered to the point where the latent spores of B. oedematiens can germinate, multiply, and produce the powerful toxin that results in the full clinical picture of black disease. Initially Turner used a guinea pig model, and then went on to show this sequence in the sheep.

Control strategies and vaccine development

It was brilliant work, undertaken with meticulous care and attention to scientific detail, which identified the natural history of the disease. It also demonstrated that a two-fold attack on the problem was possible.

- First, one could attack the intermediate host of the sheep liver fluke (which is the snail, Lymnaea tomentosa) by clearing water channels and treating these with copper sulphate at the rate of 25 to 30 pounds of ‘bluestone’ per acre.

- Alternatively one could use carbon tetrachloride in paraffin oil given to sheep as a drench. However, carbon tetrachloride in larger doses than recommended in the drench for sheep caused liver damage, which might initiate black disease in sheep carrying B. oedematiens spores as readily as did invasion of the liver by immature flukes.

- The second line of attack was the development of a vaccine made from six field strains of B. oedematiens (now known as Clostridium novyi), grown in a special V-F broth, developed by Weinberg for growing anaerobic bacteria (V-F = viande-foie, a peptic digest of heart muscle, beef liver and pig stomach tissue). After growth, when maximum toxin production had occurred, the cultures were treated with 0.4% commercial formalin until sterile. Such anacultures are innocuous, and were found to produce good immunity to black disease when given in two doses subcutaneously. Extensive field trials showed the value of this vaccine, and many thousands of sheep were inoculated with vaccine produced by Turner and supplied by CSIR, free of charge, to sheep breeders throughout Australia in 1930.

Thereafter, the vaccine, made according to Turner’s formula, was prepared and distributed by the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories (CSL). Donald Thomas Oxer in 1937 modified Turner’s vaccine by adding alum, to produce an alum-precipitated vaccine, which produces a greater and more prolonged response in sheep, following administration of a single dose. This type of vaccine was produced by CSL and used throughout Australia and other parts of the world to control black disease.

Publications and a DVSc

The results of Turner’s five years’ work on black disease were published by CSIR in 1930. This work formed the basis of Turner’s thesis submitted to the University of Melbourne early in 1930 for the DVSc degree. JA Gilruth, Chief of the CSIR Division of Animal Health at that time, wrote a foreword to this Bulletin. He indicated that the thesis had been accepted, and he quoted the following from the examiner’s report:

The thesis of Mr AW Turner is, in the opinion of all the examiners, a remarkably fine piece of work of quite outstanding merit. The work reveals a profound knowledge of the subject in hand, its literature and its techniques, a critical sincerity combined with a breadth of outlook ‘ an awareness of possibilities ‘ which combination is the essential for any first class research work. The work embodied in this thesis is a comprehensive study, bacteriological, pathological, experimental, and, not only constitutes an elucidation of a problem of animal pathology, but is a valuable contribution to preventive veterinary medicine of great economic importance to Australia. The thesis is alike a credit to the author, to the University of Melbourne, and to the Commonwealth Council for Scientific and Industrial Research

As might be expected from such a report, the University accepted Turner’s thesis in July 1930, and he was admitted to the degree of DVSc in September of that year. The published papers on this work were submitted by Turner for the Syme Prize of the University of Melbourne which he received in 1932.

An important diversion – the fight against contagious bovine pleuropneumonia

Turner’s work on anaerobic bacterial infections of livestock was interrupted when CSIR sent him to Townsville in late 1931, to work on the problem of the eradication of contagious bovine pleuropneumonia described elsewhere in this series.

Continuing studies of Clostridium species

On his return to Melbourne in 1936, Turner quickly re-established his work on anaerobic infections. With Catherine E Eales as his assistant, he published further papers on Cl. oedematiens, two dealing with the interesting phenomenon of motile daughter colonies produced by several clostridial organisms, and another reporting a study of the ‘H’ and ‘O’ antigens of Cl. oedematiens. This latter paper, involving a study of 33 strains, required a considerable volume of careful work which led to the conclusion that a serological subdivision of the group was not possible. The cultural, biochemical and pathogenic relationships of these organisms were stated to form the subject of another communication which, however, was not published.

He also studied the toxins produced by the anaerobe, Clostridium welchii, now known as Cl. perfringens. This species had been divided into four types on the basis of their exotoxins. Type A, involved in gas gangrene of human beings and animals, and type D, responsible for enterotoxaemia of sheep and cattle, were those of main interest to veterinarians. These studies included: the development of a method of producing large quantities of Cl. perfringens alpha-toxin free of theta-toxin (published in 1942, in Nature, 150, pp.549-550); and a collaboration with Charles Kellaway (Director of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research) and Everton Rowe Trethewie on the neurotoxic and circulatory effects of the toxins of Cl. welchii type D.

With Alan Rodwell he focused his attention on the epsilon-toxin, produced by Cl. welchii type D, since this was the toxin mainly responsible for toxaemia in sheep. They reached the important conclusion that the conversion of Type D prototoxin to toxin might involve the proteolytic removal of part of the prototoxin molecule which ‘masked’ the toxicity of the molecule, a suggestion that was later shown to be correct. These observations provided two important facts: they explained the very rapid onset of enterotoxaemia in sheep infected with Cl. welchii type D, and also provided the vaccine manufacturer with a means of producing potent toxin preparations for conversion into toxoid vaccines for protection of animals in the field.

Honours and awards

Turner received many honours and awards for his scientific work including:

- DVSc from the University of Melbourne in 1930

- DSc

- Syme Prize from the University of Melbourne in 1932

- Life Member of the Australian Veterinary Association

- Foundation Life Fellow of the Australian College of Veterinary Scientists

- Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1938

- Fellow of the Australian Academy of Science in 1954

- Membership of the Wallaby Club of Victoria, a select club for men distinguished in science, the law and letters

- Gilruth Prize of the Australian Veterinary Association in 1958, the highest honour his profession could confer on him.

Source

- French EL, Sutherland AK, 1992, Biographical memoirs: Arthur William Turner 1900-1989 (Australian Academy of Science)