Cobalt deficiency and the cure for coast disease

A cure for coast disease, a wasting disease of sheep, was discovered in the late 1930s by Hedley Marston and his team at the Division of Animal Nutrition. The disease had baffled veterinarians since the early days of settlement and was common along the coast from Victoria to South Australia. Scientists identified the cause of the disease as cobalt deficiency. Sheep were treated with cobalt pellets given orally by means of an applicator.

The impact of this development is illustrated in the following anecdote. In 1937 under a windswept clear blue sky a score of lambs frisked, stiff-legged and tails bobbing, over rolling sand-dune pasture at Robe, on the south-eastern coast of South Australia. Farmer Bob Dawson tipped back his hat and a grin split his weathered face. Pretty good, John

CSIRO scientist John Lee could not reply. He simply nodded and the two men stood in silence watching the beginning of a miraculous change at Robe. For the first time since Bob Dawson’s father took up the property in 1877 a spring crop of lambs had not only survived, but thrived. The land that had broken Bob Dawson’s heart for 40 years had given up its sour secret and had been beaten. Two years later a flock of Bob Dawson’s lambs fetched top price at a nearby market.

Cobalt deficiency was also identified as the cause of Denmark disease in cattle, and cobalt supplementation as a treatment for the nerve degenerative condition in sheep known as Phalaris staggers.

Coast disease – a frustrating problem

The land at Robe on the south-eastern coast of South Australia looked promising enough to the first settlers. It had a good reliable rainfall; the rough scrub and native grasses were readily cleared for pasture. But the settlers soon found that sheep grazed on these pastures lost their appetite and their wool became ‘steely’ and dead-feeling. If the sheep were not moved inland every year they became anaemic, lethargic and wasted away until, often, they died.

The settlers called this mysterious ailment coast disease. Similar and equally mysterious wasting diseases occurred in many parts of the world; in the south-west of Western Australia cattle were afflicted with what the locals called Denmark disease. Many farmers quit the south-eastern coast forever and today their abandoned farm-houses, with blind and broken windows and roofs gaping at the sky, remain as mausoleums of their defeat.

Probable cause – nutritional deficiency

In 1928 visiting South African veterinarian Sir Arnold Theiler suggested that coast disease might be caused by a deficiency of phosphorus. Ted Lines of the CSIR Division of Animal Nutrition in Adelaide dosed ‘coasty’ sheep on Kangaroo Island with phosphate. The sheep died even more quickly than usual.

But at the same time another member of the Division, Dick Thomas, a chemist with a background in geology, was mapping out the areas affected by coast disease on Kangaroo Island. He recognised that these areas had calcareous soils formed during the last Ice Age when the continental shelf was exposed and prevailing winds blew fragmented shell material inland. He believed that all these soils would be short of traces of heavy metals, some of which were already known to be essential animal nutrients.

Cobalt deficiency identified as the cause of coast disease in sheep

At that time the Division’s senior biological officer was Hedley Marston, a brilliant man with a huge capacity for absorbing knowledge and making olympic jumps to conclusions. Marston later became Chief of the Division and had a major influence on trace-element research in Australia for more than 20 years. Dick Thomas drew Marston’s attention to a report by two German scientists who had induced an excess of red blood cells in rats by feeding them with cobalt. As a profound anaemia with a gross lack of red cells was a common feature of coast disease, Thomas reasoned that a deficiency of cobalt in coastal soils might be responsible.

The scientific correlation was fragile, to say the least. Nevertheless, Marston felt it was a lead worth following and he suggested to Ted Lines that he dose sheep on Kangaroo Island with a mixture of trace minerals including cobalt, nickel, molybdenum, copper and zinc. The mixture proved beneficial but the element, or elements, responsible still needed to be identified. Lines was hampered in his field tests by the fluctuating severity of the disease until the Chief of the Division, Sir Charles Martin, suggested that he set up an experiment at the Division’s headquarters, at the University of Adelaide, using penned sheep fed on a coasty diet. In 1934 he dosed his now coasty sheep with pure cobalt nitrate ‘ one milligram a day ‘ and achieved for the first time a clear-cut cure.

Cobalt deficiency identified as the cause of Denmark disease in cattle

Late in 1934 Eric Underwood, an animal nutrition officer with the Western Australian Department of Agriculture and later a member of the CSIRO Executive, visited the Division and described the work that he and his colleague John Filmer had been doing in Perth on Denmark disease in cattle. At that time they suspected the disease was due to a dietary deficiency of traces of either: zinc, manganese, nickel or cobalt. Dosing cattle with a nickel compound had proved moderately successful; however, it turned out later that the compound used had been grossly contaminated with cobalt. The Adelaide scientists listened to Underwood’s findings and then took him outside to show him the sheep that had been cured with cobalt. Underwood returned to Western Australia to learn that further experiments with a purer nickel salt had been unsuccessful. Zinc, manganese and cobalt were then tested, and cobalt was shown to cure Denmark wasting disease of cattle.

Cobalt delivery problems

Back in Adelaide, CSIR veterinarian Dan Murnane extended Dick Thomas’s geological surveys and his findings led Marston to enlist the help of grazier Bob Dawson and the use of his property. The quantities and frequencies of cobalt dose rates were formulated and research teams turned their attention to another trace element ‘ copper.

Early studies had shown that copper was also lacking in coasty sheep. But while copper deficiency could be readily overcome by adding copper salts to the fertilisers used on the pasture, the prevention of cobalt deficiency was not so easy. For some reason, cobalt didn’t work when applied in this way. Sheep also failed to respond to injections of cobalt and the only satisfactory way of administering it was by drenching ‘ a time-consuming and back-breaking task.

It was clear that dosing with cobalt only worked if the cobalt found its way into the rumen or paunch of the sheep. But why this should be so was not to become clear until the 1950s. Moreover, it was not until the 1950s that a simple means of dosing sheep with cobalt was developed.

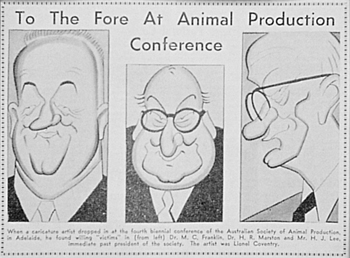

In 1955 a visiting Fulbright Fellow, Perry Stout arrived in Adelaide from California, to follow up the Australian studies in which sheep had been saved from a fatal condition called phalaris staggers by dosing with cobalt. Staggers, a degeneration of the nervous system, can occur at any time and without warning among sheep grazing freshly growing pastures of the grass Phalaris tuberosa. To prevent the condition sheep must be given cobalt when grazing green Phalaris.

One morning Stout walked into John Lee’s office at the Division of Animal Nutrition, pushed a pile of papers off his cluttered desk, and plumped down with the bluff announcement that he had an idea.

Say, John, he boomed, why don’t we go about this a different way?

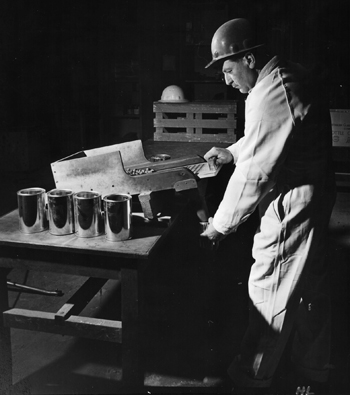

The problem, as he saw it, was to keep a constant supply of cobalt in the sheep’s rumen. So why not bung in a metal container, filled with cobalt, and fitted with an asbestos ‘wick’ which would leak out a regular supply of cobalt? Ten minutes later in the Division’s workshop the two men had crafted a rough capsule of brass tubing, about 40 millimetres long, which they coated with paraffin. Using a larger tube as a blow-pipe, Lee blew the capsule down a sheep’s throat. Later, X-rays showed the capsule had lodged safely in the sheep’s reticulum, a sub-compartment of the rumen.

Work then began in earnest to perfect a capsule or pellet that could be made on a production line. Eventually a ceramic pellet containing 90 per cent cobalt oxide was devised.

Problems with first field trials of cobalt capsules

Marston was keen to publish the news of this breakthrough but was persuaded that it should first be field-tested in an area where sheep suffered Phalaris staggers. A property at Bool Lagoon, south of Naracoorte, was chosen and 200 sheep were dosed with cobalt pellets and confined to Phalaris pasture along with 50 untreated sheep. Not one of the treated sheep got staggers but 49 of the untreated sheep did. Marston announced the success, patents were taken out, and commercial production under licence went ahead.

Then a few weeks later, disaster struck. Some of the treated sheep at Bool Lagoon developed staggers. At first this appeared to be a shattering setback – then post-mortems revealed that not one of the sheep affected had a pellet in its stomach. All of the missing pellets had been regurgitated.

So yet another line of research had to be followed, in developing a pellet with a specific gravity high enough for it to remain in the sheep’s stomach. The solution was to mix the cobalt with heavy iron filings. But a final snag remained. Secretions in the sheep’s rumen often coated the pellets with calcium phosphate which stopped the release of cobalt. The ingenious solution to this problem was to market cobalt pellets with a second device ‘ a short length of threaded steel rod which would rub against the pellet in the sheep’s rumen and grind away the calcium phosphate coating.

The laborious work of regularly drenching sheep in Phalaris staggers and coastal disease country became, ‘mercifully’ a thing of the past. Robe, and the country all around it, took on a new and promising aspect. Land that men had once turned their backs on fetched up to $200 a hectare.

Why cobalt?

The final, and continuing, thread of the cobalt story lies in tracing the role of cobalt in the nutrition of sheep and other ruminants.

The first clue to this came in 1948 when research teams in Britain and the United States isolated from liver a compound which they named vitamin B12 and showed that each molecule of the new vitamin contained one atom of cobalt. It was later found that this vitamin is produced in sheep by the microorganisms that live in its rumen. Humans have no such microorganisms and must rely on their diet to provide them with the vitamin B12 they need.

In 1954 several lines of research came together and Marston proposed that a vitamin B12 deficiency in sheep caused by a lack of cobalt in their diet depressed their appetites, resulting in a vicious circle which further lowered their cobalt intake. A biochemical explanation of this phenomenon was provided later when it was discovered that vitamin B12 is an essential component of a particular enzyme in the sheep’s liver. Lack of this enzyme leads to a build-up of propanoic acid in the blood stream and consequent suppression of appetite.

Most recently investigations into the intersection between vitamin B12 and another B vitamin, folic acid, have cast new light on pernicious anaemia in humans. And so, in a huge sweeping circle the research that man began into a wasting disease in sheep in the late 1920s, has returned – to himself.

Epilogue

In 1975 Bob Dawson was still living on his property, Belle Vue. He was an old man of 98, but with undimmed memories of the remarkable bloom of life brought to the country once blighted by coast disease. Many farmers did not have the dour determination that made Bob Dawson hang on to his unrequiting land, even though it meant labouring as a slaughterman, butcher and road-maker to support his family.

He was proud of his MBE, awarded for his contribution to agricultural research; in the early days of investigation into coast disease his property Belle Vue was designated a CSIR experimental farm and he was made a field officer. He held the position until he was 96, the Australian Government’s oldest ‘employee’.

Source

- McKay A, 1976, ‘Cobalt and coast disease’, Surprise and Enterprise, Fifty Years of Science for Australia, White F, Kimpton D (eds), CSIRO Publishing, pp.18-20.