John Anderson Gilruth (1871-1937)

John Anderson Gilruth was born on 17 February 1871 at Auchmithie, a fishing village near Arbroath, Forfar, Scotland, second child of Andrew Gilruth and his wife Ann, nee Anderson. His father was a tenant farmer of the Carnegie family, the earls of Northesk. His mother, a teacher before marriage, was a woman of character and intellect; John always considered her to be the major influence upon his life. He attended the village school at Auchmithie, where, according to his recollections late in life, reading and writing were confined to the Bible and early Scottish history which left him with a fixed impression that Robert Bruce was the father of Queen Victoria.

Gilruth went on to high school at Arbroath and, briefly, Dundee. During holiday periods he spent much time with Jamie Macdonald, a perceptive shepherd who inspired his interest in the problems of animal management and disease. Under family pressure Gilruth spent two years as clerk to an Arbroath solicitor before his father agreed to let him go to Glasgow Veterinary College in 1887. In his first year he took medals in botany and anatomy and went on to sweep the board in all subjects at the examinations of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, London, before being admitted to membership of that institution in 1892.

In New Zealand

Soon afterwards Gilruth applied for, and received appointment as, a government veterinary surgeon in New Zealand. He arrived there late in 1893 and spent three years investigating stock diseases. In 1896 the government sent him to study bacteriology at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. Upon his return in 1897 he became chief veterinarian and government bacteriologist. A pioneer of his profession in New Zealand, he proved a vigorous and able leader both in research and in the movement for upgrading standards of meat inspection and slaughtering. In 1900 he was appointed a member of the royal commission on public health in New Zealand and a year later became pathologist to the newly formed Health Department. In appreciation of his work with that department the New Zealand branch of the British Medical Association made him an honorary member in 1902. His career prospered to the extent that in 1904 the government blocked a move to offer him a lucrative post in South Africa, on the ground that New Zealand could not afford to lose his services. In 1907 he became a fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

Gilruth usually preferred directness to diplomacy. It is said that a well-known sheep-breeder once asked him why his young ewes would not thrive, whereupon Gilruth replied, ‘Why don’t you feed your bloody sheep?’ In this case he was right and friendship resulted. But his forthrightness in pressing for improvements in research facilities and health measures raised tensions with government officials and the Minister for Lands.

Move to Australia

He became increasingly frustrated, despite the warm support of his colleagues and farmers’ organizations, and when the University of Melbourne offered him the newly created chair of veterinary pathology in 1908 he accepted. With characteristic energy, he turned to building up the veterinary faculty and its associated research institute. His teaching methods, unorthodox at the time, aimed to stimulate students’ curiosity. Gilruth set a fine example by his own passion for his work which, during this period, included investigations of fundamental importance into black disease and entero-toxaemia. In 1909 the university awarded him an honorary doctorate of veterinary science.

In 1911 Australian Prime Minister Andrew Fisher invited him to join a scientific mission to investigate the potential of the Northern Territory. The leader of the mission, Professor (Sir) Baldwin Spencer, was his colleague and friend and, as first Commonwealth-appointed protector of Aborigines, later his adviser. Gilruth’s northern expedition fired him with enthusiasm for economic development of the Territory by means of mining, crop-growing and pastoralism. In February 1912 he accepted from the Fisher government the post of Administrator of the Northern Territory. Two months later he arrived in Darwin, confident of his own leadership ability and of strong government support for his developmental plans.

From the beginning his plans went awry. Territorians and the Federal government alike held unrealistically high hopes for economic development, yet half expected failure because such was seen to have been the result of all earlier efforts by South Australia in the Territory. Thus every set-back was doubly condemned. Gilruth did his best to promote agriculture, mining and, after initial doubts, the development of meatworks in Darwin by the giant English firm, Vesteys. All proved disappointing. With the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, an already wavering Commonwealth government lost interest in Territory development. The one great hope, Vesteys’ meatworks, closed in 1920 after a consistent history of industrial unrest and cost inflation.

The weight of public frustration fell upon Gilruth quite unjustly, yet his own character helped to bring about that result. Among scientists of similar background and interests, his blunt, dynamic style of leadership was respected and he was able to show best the personal kindliness and loyalty which endeared subordinates to him. Among the heterogeneous population of the Northern Territory he was seen as arrogant and insensitive. Tutored by Spencer, he went to Darwin predisposed to treat the Chinese with reserve, the Aboriginals with heavy-handed paternalism and the white trade unionists with suspicion. In June 1913 the real wages of government field-survey hands were arbitrarily reduced. When the fledgling Amalgamated Workers’ Association staged a strike over the matter, Gilruth crushed it ruthlessly and earned the enduring enmity of the union leaders.

Harold Nelson, the able organizer (later secretary) of the Darwin branch of the Australian Workers’ Union, skillfully used the antagonism to isolate Gilruth while he built his union into the great industrial power of the Territory. Gilruth’s response was hindered by the Commonwealth government which neither gave him the powers he needed to rule effectively nor evolved consistent policies for the region. His own officers clashed with him over industrial matters and he upset the small group of Darwin employers over his attitude to town lands and the abolition of the Palmerston Council. Only among the graziers did he find sympathy. His greatest pleasure was to take long drives through the outback in his Talbot, the first car seen in nearly all the areas he visited.

On 17 December 1918 public discontent peaked in a confrontation between Gilruth and townspeople which became known as the ‘Darwin Rebellion’. Gilruth, with the courage which never failed him, faced an angry mob demanding that he leave Darwin. In February 1919 the government recalled him for consultation and eight months later some of the Darwin citizenry forced the departure of three of his close associates, HE Carey, director of the Northern Territory, DJD Bevan, judge of the Supreme Court, and RJ Evans, government secretary. Reacting sharply, the Hughes ministry appointed Mr Justice NK Ewing as Royal Commissioner to investigate the causes of these events. Ewing immediately cast doubt on his impartiality by hiring Nelson, the union leader as ‘representative of the citizens of the Northern Territory’ to assist at the hearings. Ewing’s report, completed in April 1920, accused Gilruth of allowing irregular practices in the courts and Aborigines Department and of personal impropriety in land and mining deals. Mr Justice Kriewaldt later described the report as ‘a shoddy piece of work’ with some justification since the evidence does not support any of these findings, but Ewing was right in believing that, for all his great abilities, Gilruth was not fitted ‘to rule a democratic people’.

Sir Robert Garran, Commonwealth solicitor-general, absolved Gilruth from Ewing’s charges of impropriety, but the government treated him shabbily, evading the promise of a post with the Institute of Science and Industry.

At CSIR

Gilruth battled through the 1920s as a private consultant, but in 1929 became consultant to, and next year Acting Chief of, the newly formed Division of Animal Health within CSIR; he became Chief of the division in 1933. He regained his zest for research and under his inspired guidance the scattered activities of existing organizations working on animal health were co-ordinated. To facilitate the study of problems associated with cattle raising in tropical and sub-tropical Australia, Gilruth arranged the temporary transfer to CSIR, in September 1931, of the Queensland government’s Stock Experiment Station at Oonoonba, Townsville. On his recommendation Zebu cattle were later introduced for cross-breeding. In November 1931 the McMaster Animal Health Laboratory was opened in Sydney in the grounds of Sydney University. The same year Gilruth was appointed chairman of a committee consisting of representatives of CSIR and the New South Wales Department of Agriculture to direct the study of fly-strike in sheep (see Sheep blowfly and other insect pests), and in 1933 he was appointed to a committee to survey coast disease in South Australia (see Cobalt deficiency and the cure for coast disease). In 1934 Gilruth reported on the beef-cattle industry in northern Australia and on the general possibilities of the north; he also conducted an inquiry into the organization of the Tasmanian Department of Agriculture. During his period in charge of the Division of Animal Health many of the problems on which he had personally worked were brought nearer solution.

In 1933 he was elected to the presidency and in 1936 to honorary membership of the Australian Veterinary Association. His publications on veterinary research in the professional journals were voluminous.

Retirement

Gilruth’s retirement in 1935 was regretted by his senior colleagues, many of whom had been his students and by whom he was regarded with respect and affection. He died of a respiratory infection on 4 March 1937 at his home at South Yarra, Melbourne, and was cremated. His wife Jeannie McLean, nee McLay, whom he had married on 20 March 1899 at Dunedin, New Zealand, a son and two daughters survived him.

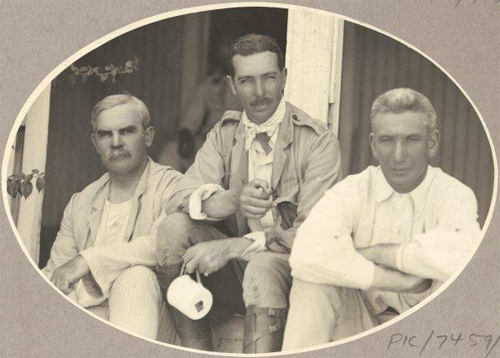

His name is commemorated in Gilruth Plains, a research station near Cunnamulla, Queensland, and by the Gilruth prize of the Australian Veterinary Association. The city of Darwin remembers him in the name of an avenue. His portrait by the artist William Frederick (Will) Longstaff (1879-1953), hangs in the Australian Animal Health Laboratory in Geelong, Victoria.

Honours and awards

Fellowships and memberships

| 1936 | Honorary Membership, Australian Veterinary Association |

| 1907 | Fellow, Royal Society of Edinburgh |

| 1902 | Honarary Member, British Medical Association |

Awards

| 1909 | Honorary doctorate of veterinary science, University of Melbourne |

Source

Powell A, 1983, ‘Gilruth, John Anderson (1871–1937)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/gilruth-john-anderson-6393/text10927, first published in hardcopy in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 9, (MUP), 1983.