Mechanised cheese making

The ancient art of cheese making has been a very traditional industry with knowledge and ‘secrets’ handed down from generation to generation. It was an important industry in Australia but was in decline after the second World War due to problems with poor starter cultures and the impact of virus (bacteriophage) infections.

Within two years of joining CSIRO’s Division of Food Research, Józef Czulak solved the starter culture/virus infection problems and then over the next 20 years led a team that changed the nature of the cheese industry. Despite considerable skepticism they showed that cheese making, which up to that time had been considered an art, could be mechanised.

This led to a major reorganisation of the Australian industry and by the mid 1970s Bell-Siro Cheese-maker machines were installed not only in Australia but in New Zealand, Britain, Ireland, Holland and the United States.

Cheese making – from antiquity to modern times

The secret of cheese-making was discovered possibly 6 000 years ago. Certainly the ancient Greeks knew it. Homer composed songs about cheese and the goddess Aphrodite was said to have sent gifts of cheese to the warriors of Troy. The knowledge spread throughout Europe and became shrouded in mysteries and rituals as it was passed from generation to generation.

The early settlers brought their knowledge of cheese-making to Australia and by 1870 the first factories had opened on the rich dairy-farming country of the south coast of New South Wales. Manufacture spread and further cheese factories were built to keep pace with Australia’s growing population. During World War II a hungry Britain sent pleas for more food and manufacture expanded still further.

Post World War II decline in the industry solved

After the war the industry in Australia went into a decline, worsened by the trouble that cheese-makers were having with starter cultures of fermentation bacteria which refused to multiply satisfactorily, and with a virus infection that was killing the bacteria.

The CSIRO Division of Food Research placed advertisements in British newspapers seeking scientists who might solve the problem. One answer came from Józef Czulak, a former Polish cavalry officer who had survived the heroic charges against Hitler’s panzer tank battalions in the battle for Poland. He had later taken part in the Normandy invasion, which qualified him for British repatriation and enabled him to take an Agricultural Science degree and a Postgraduate Diploma in Bacteriology at Reading University.

I had a farming background and I wanted to do practical science

The Division asked Czulak to come to Australia and he arrived in 1951 with his Scottish wife. Two years later he had beaten both the starter-culture trouble and the bacteriophage infection problem.

Is mechanisation possible for an industry based on ‘art’

Then the Division turned to the mechanisation of cheese making, at a time when the industry still regarded technology with deep suspicion. A leading British dairy scientist said:

I fear that we are in very great danger of thinking that the engineer can solve the problem of the mechanization of cheese-making. Despite the assistance of the engineer and the scientist, cheese-making is still an art.

In fact, mechanical agitators were already in use in the first phase of cheese-making, the conversion of milk to curds and whey and the ‘cooking’ of the curd. Curds are the coagulated solids in milk which compose most of the protein and fat, and whey is the pale yellowish liquid that is left.

The rest of the cheese-making process can be divided into a further three phases. In the second or ‘cheddaring’ phase, the free whey is drawn off and the curds are fused into large slabs with a fibrous texture. In phase three the slabs are milled into finger-sized pieces, salt is added, and the salted curd is placed in large drums or in stainless steel hoops. The fourth phase involves compressing the curd and packaging.

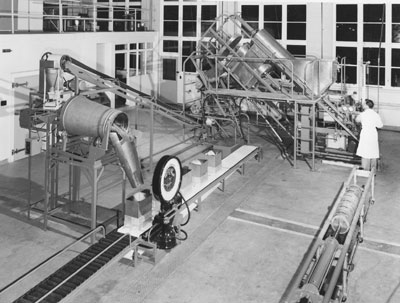

Pilot scale process

By 1957, Józef Czulak and a team of engineers and technologists had built a pilot system combining phases 1, 2 and 3. A film of the plant in operation was shown to the largest meeting of cheese-making experts to gather in Britain and their response was enthusiastic, if still cautious. In Australia, suspicion lingered on.

Resistance was colossal

Commercial operations

Phase 3, the most labour-intensive operation, was tackled first and by 1960 the first commercial machine, developed by the food engineering company Bell Bryant Pty Ltd with CSIRO, went into operation. Fifteen years later more than 50 Bell-Siro Cheese-maker 3 machines were working in Australia, New Zealand, Britain, Ireland, Holland and the United States. These machines could handle up to 4 530 kilograms of curd an hour, the economical limit at that time.

In 1967 the first phase 2 machine, Bell-Siro Cheesemaker 2, was installed in a New Zealand factory, followed in 1970 with an improved model in a factory at Camperdown, Victoria. The new model gave greater flexibility in the types of cheese made and could be used to produce Cheddar, Cheshire, Cheedam, Colby, stirred-curd and Romano cheese varieties. Between them, Cheesemakers 2 and 3 cut labour costs in the Australian industry by two-thirds.

In 1975, Bell-Siro Cheesemaker 4 went to work at Lismore, NSW, revolutionising the final phase with a huge hoop-press, producing 453-kilogram blocks of cheese instead of the traditional 18-kilogram blocks. All the machines were self-cleaning, previously a messy business that used to take up to five hours, and two technicians now do the work of 20 cheese-makers.

Impact

The mechanisation of cheese-making, together with other economic factors, led to a vast reorganisation of the Australian industry by the mid 1970s. Sixty factories were absorbed into 12. And, with mystery replaced by scientific control, cheese quality in all varieties has improved. In 1952 the average Australian ate less than three kilograms of cheese a year. By the mid 1970s he ate twice as much.

Source

- McKay A, 1976, ‘Mechanizing cheese making’, In: Surprise and Enterprise, Fifty Years of Science for Australia, White F, Kimpton D (eds), CSIRO Publishing, pp.10.

- Say Cheese! Scientists, Cheesemakers Meet, 1998 (Media Release)

- CSIRO’s history: the 1960s (Fact Sheet)