Our origins 1901-1926

Australia’s CSIRO has a history that can be traced back to the earliest days of the Australian Federation in 1901. The first concrete steps took place in 1916 when Prime Minister Billy Hughes established the Advisory Council of Science and Industry, which evolved to the Institute of Science and Industry in 1920. Both institutions struggled for funding and a clear mandate as the fledgling Commonwealth Government contested its role with the States and as war and economic challenges shaped the young nation.

In 1926, Prime Minister Stanley Bruce revised the Science and Industry Research Act, changed the leadership arrangements and started to increase the funding. The Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) emerged from these changes and the organisation grew rapidly and accumulated early successes. The Science and Industry Research Act was changed again in 1949 to form the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), which continues under this Act to this day.

2016 is thus the centenary year of Commonwealth Government engagement in civil science for Australian industry and community benefit.

Prologue | The 1901-1915 period | Developments in 1915/16 | The Advisory Council 1916 to 1920 | The Institute of Science and Industry – 1920 to 1925

The emergence of CSIR in 1925/1926 | Key dates and developments | Key speeches

Prologue

Good things rarely come easily. On 1st January 1901, the Australian colonies chose federation after a 12 year public debate and much dissension and emotion. For 25 years following federation, the place for science in the national affairs of Australia was also highly contested. A critically important first step was the creation on 16th March 1916 of the Advisory Council of Science and Industry.

The Council was made up of government and industry leaders and respected University professors with operations falling to an Executive Committee supported by a network of State Committees. A secretariat of three professional staff, premises on loan from other parts of the fledging Federal Government and modest funding of around 500 pounds in the first year of operations for research activities were provided by the Commonwealth. From such small beginnings grew Australia’s internationally renowned national science institution, CSIRO.

The 1901-1915 period

Over the period 1901 to 1915, there were various attempts to establish a national Bureau of Agriculture with research functions given agriculture dominated Australia’s export economy over that period. All attempts failed and there was generally strong State opposition to what was seen as mission creep in Federal powers under the constitution of the fledging nation.

This story starts in the first Federal election campaign. Some candidates seeking election advocated the establishment of a Federal Department of Agriculture or a Federal Bureau of Agriculture. These included Alfred Deakin, Isaac Isaacs, Sir John Quick and W H Groom. Sir John Quick, the Member for Bendigo, only six weeks after the Federal Parliament first assembled on May 9 1901, moved a motion that ‘a national department of agriculture and productive industries on the same lines as that of the USA’ be established.

Similar Bills were moved in 1909 and 1913 but were not passed into law. Littleton Groom, the member for Darling Downs, was a supporter of the 1901 bill and as Minister for External Affairs, introduced the 1909 bill. This bill lapsed because parliament was prorogued. Groom didn’t give up but instead of re-introducing the bill, invited a group of distinguished Scottish agriculturalists to report on agricultural developments and opportunities. They noticed a lot of duplication of effort and recommended a Federal department.

Two other investigations have a bearing on this story. The first was the Dominions Royal Commission of 1913 which investigated trade and commerce and the Empire. Discussions between the Commissioners and the Imperial Institute (in London) resulted in ‘Outlines of a scheme for co-ordination of the work of the Imperial Institute with that of bodies doing similar work in the self-governing Dominions’. This paper was submitted on 24 June 1914. WW1 broke out on 28 July 1914 so it had no effect. It did indicate that the benefits of collaboration between like institutions were being recognised.

Of greater significance was the October 1915 report of the Australian Interstate Commission. This was a report requested by the Minister for Customs ‘That the Commission should furnish for the information of Parliament a report of new industries which, in its opinion could with advantage, be now established in the Commonwealth’. This report pointed out how the systematic application of scientific knowledge had been fostered to great advantage by the Government of Germany, we in Australia hadn’t done it at all.

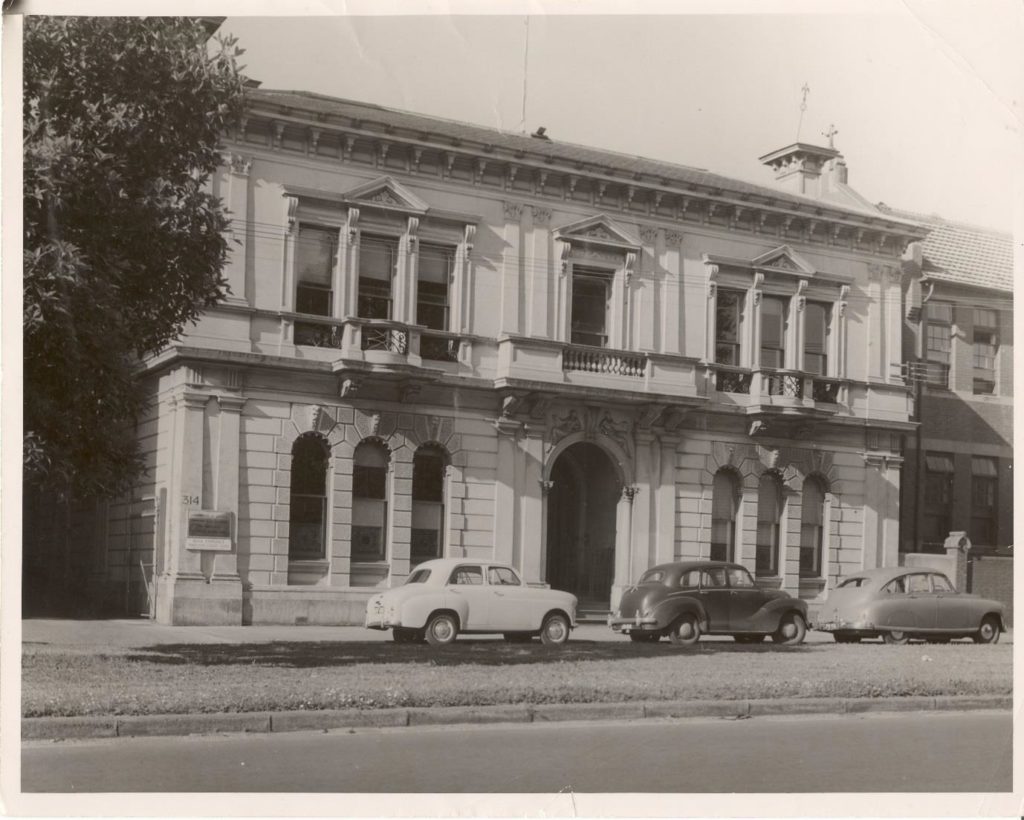

The Interstate Commission only existed for seven years from 1912 to 1919. George Swinburne was one of its three members. It was located in a Commonwealth property at 314 Albert Street East Melbourne and it made space for the Secretariat of the Advisory Council of Science and Industry in this building at its establishment in 1916.

In other developments, the Dept of Defence engaged the federal Government’s first scientist in 1909, Cecil Napier Hake, whose role was to advise on scientific and technical matters associated with the manufacture of explosives. This appears to have been uncontroversial given the strong constitution powers of the Commonwealth over Defence. Aside from this focused defence interest, the Federal Government had no formal engagement in science at the outbreak of World War 1 in 1914.

Developments in 1915/16

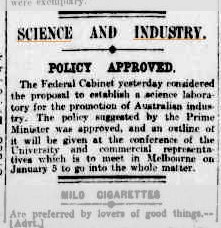

The Argus, 1 January 1916

On the 22nd December 1915, a momentous day in Australian history when the last ANZAC troops were withdrawn from the beaches of Gallipoli, Prime Minister W.M. (Billy) Hughes rose to speak at a meeting at the University of Melbourne convened by the University Council and involving some State Premiers and Ministers of Agriculture. He surprised all, shocked some and thrilled others in the audience when he announced the Federal Government’s intention to set up a national institution for scientific research. Developments in Europe, including the apparent technological superiority of Germany (the WW1 foe) in agricultural and industrial domains and the development of a national scientific research department in Britain (DSIR) in July 1915 appear to have fuelled PM Hughes recognition that science was going to be the foundation of the fledging nation’s national security and industrial and economic success.

Acting with remarkable speed, the Prime Minister convened a conference in Melbourne on the 5th January 1916 to develop a plan for a “national laboratory”. This was chaired by PM Hughes and involved State Ministers of Agriculture, representatives of State universities, and industry representatives.

Later in January 1916, PM Hughes left for a extended trip to the USA and Britain to confer on the war effort but took with him Gerald Lightfoot to investigate scientific institutions in the USA and UK. Gerald Lightfoot would feature in this narrative in important ways over the next 30 years. With the state of war and perhaps the state of politics, PM Hughes opted to have the Governor General gazette the Advisory Council of Science and Industry on 16th March 1916 as a “temporary” step towards a permanent Institute for Science and Industry to be established under an Act of Parliament.

The Advisory Council 1916 to 1920

The Advisory Council of Science and Industry was located here, at 314 Albert Street, East Melbourne.

The Advisory Council was made up of government and industry leaders and respected University professors with operations falling to an Executive Committee supported by a network of State Committees. It was always intended to be a temporary body, pending the passing of legislation to establish what was referred to at the time as the permanent “Institute”.

It had a small Secretariat led by Gerald Lightfoot (in 1916 an officer of the Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics) and was headquartered at the Commonwealth offices in 314 Albert St East Melbourne (on loan from the Interstate Commission 1912-1919). The Advisory Council had three professional staff, a Chairman, a CEO and a technical officer and a small budget (Pounds 541 in 1915/16 growing to Pounds 13,109 in 1919/20).

The Advisory Council invested in research projects and commissioned investigations on matters of science relevant to industry development in Australia. The first research project was a co-investment with Qld and NSW Governments to tackle the scourge of the invasive weed prickly pear which was spreading rapidly over millions of hectares of good agricultural land.

The Institute of Science and Industry – 1920 to 1925

The Advisory Council’s mandate was also to lay the groundwork for a permanent “Institute of Science and Industry” which was ultimately established in 1920/21 under an Act of the federal parliament. The Advisory Council’s budget was small and impact limited, mainly scoping reports on a diverse range of scientific and industrial development matters.

Attempts to establish the permanent Institute of Science and Industry via Act of Parliament failed in 1918 and it was not until 14th September 1920 that the Act for the Institute of Science and Industry passed through both houses of federal Parliament. George Knibbs (later Sir George), then the Commonwealth Statistician, was appointed the first Director of the Institute of Science and Industry on 18th March 1921. Gerald Lightfoot was Secretary and the Institute’s headquarters was once again, 314 Albert St East Melbourne.

The short lived history of the Institute, from 1921 to 1926 was dominated by problems of lack of funding, staff and research facilities. Only two “annual reports” were produced over five years and the work was characterised by many small projects of limited impact. The involvement in prickly pear research continued and represented the major research project in collaboration with Queensland and NSW agencies. Billy Hughes lost government in the general election of 16 December 1922 and Stanley Bruce became Prime Minister.

The Institute struggled on until 1925/26 but was never funded adequately and remained a target of attack and resistance from many States and even some parts of the Commonwealth such as the office of the Chief Analyst. In May 1925, the Bruce government called a conference with the objective of designing a “re-organisation” of the Institute of Science and Industry. Major contested issues during this reorganisation were the structure of the executive (a single Director or a broad based Council and Executive Committee) and the degree to which the federal agency would have research staff, facilities and staff in its own right or work with and through existing State capacities.

Prime Minister Bruce appointed the three person executive committee of GA Julius, WJ Newbigin and ACD Rivett in early 1926, ahead of the CSIR Act being passed by Parliament on 23 June 1926. This first Executive of CSIR was actually appointed to the Institute and were the group that proposed the name of CSIR. They had held 16 Executive meetings in the transition from Institute to CSIR prior to the assent by Parliament of the 1926 Science and Industry Research Act. Aside from these organisational matters, the powers and functions of CSIR under the 1926 Act were essentially the same as the Institute under the 1920 Act, with the except that a function around industrial welfare and conditions was replaced by a function relation to scientific liaison between the Commonwealth and other countries.

While Prime Minister Billy Hughes had the grand vision in 1915/16 for Australian science underpinning Australia’s industrial development and community well- being, he failed to create the conditions to rapidly progress that vision. He failed to garner consistent support from the States and he failed to adequately fund the grand initiative. His first choice as Director (Dr Francis Gellatly) tragically died in the Influenza Outbreak of 1919 whilst on duty travelling around the States to garner support for the proposed Institute. The second choice of Director, Sir George Knibbs, was unable to get either the Commonwealth Government or the States to put their full resources behind this vision. We will never know if the circumstances would have been any different if Frances Gellatly had not been lost in the trauma of post war influenza.

The emergence of CSIR in 1925/1926

In contrast, in 1925/26, Prime Minister SM Bruce was equally committed to Hughes’ grand vision (perhaps with less florid language), but he carefully cultivated the support of the States, carefully amended the Act to bolster this State support and reduce the reliance on the personal style of a single Director. Most importantly, the funding doubled in the first year of CSIR operations and increased five-fold by 1931.

CSIR operating with growing success and recognition until the Act was revised again in 1949 to create the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). Interestingly, the headquarters was still 314 Albert St East Melbourne and the powers and functions under the Act were little changed.

Key source: Currie and Graham (1966) The Origins of CSIRO: Science and the Commonwealth Government 1901-1926.

Key dates and developments

(Source: Currie and Graham (1966) The Origins of CSIRO: Science and the Commonwealth Government 1901-1926)

1. THE BEGINNINGS, 1901-1915

The Federal Government showed some interest in the application of science to agriculture from the first year of federation. Bills to establish

a Commonwealth Bureau of Agriculture were introduced in 1909 and again in 1913 but failed to become law.

2. HAGELTHORN AND HUGHES, 1915-1916

The exigencies of war impelled the Imperial Government to set up, in July 1915, an organization for scientific research in Britain to serve the nation during and after the war. When news of this reached Australia later in the year, moves initiated in Melbourne by the Victorian Minister for Public Works (and from 1916 Agriculture), Frederick Hagelthorn, lead to the announcement by the Prime Minister, W. M. Hughes, that a similar scheme would be established in Australia under the auspices of the Commonwealth Government.

3. THE ADVISORY COUNCIL FORMED, 1916

Formation of an Advisory Council of Science and Industry. A widely representative conference was called in January by the Prime Minister to discuss a National Laboratory to be established by the Commonwealth Government. It was decided as a first step to set up an Advisory Council of Science and Industry, to be replaced as soon as legislation could be passed by an Institute of Science and Industry. W. M. Hughes left in January to visit Great Britain taking with him Gerald Lightfoot to report on research institutions in Great Britain and the United States.

4. THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE AT WORK, 1916-1918

The Advisory Council of Science and Industry, through its Executive Committee, went vigorously to work making a census of problems to be dealt with and of scientists and facilities available to handle them. In July 1917 there was a stormy session with the Prime Minister. In April 1918 Dr F. M. Gellatly was appointed director of the proposed Institute of Science and Industry.

5. GELLATLY TO KNIBBS, 1918-1920

Gellatly worked with the Advisory Council as member during 1918 and became chairman January 1919. He worked for the Bill to establish the Institute but died suddenly in September of that year. Professor Masson resigned from the Executive and from the Council when he learnt that the Bill had been altered in ways he believed vital. The Institute of Science and Industry Act 1920 passed into law on 14 September 1920.

6. THE COMMONWEALTH INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE AND INDUSTRY,1920-1925

The Institute was established with George Knibbs as the single director but adequate funds were not forthcoming and the organisation failed to develop as had been hoped. In 1925 S. M. Bruce, having decided to reorganise the Institute, convened a conference in May to make recommendations and invited Sir Frank Heath, head of the D.S.I.R. in Great Britain, to advise his Government on the best form of reorganisation.

7. THE CONFERENCE OF 1925 TO THE PASSING OF THE 1926 ACT

The new Bill to amend the Institute of Science and Industry Act 1920 was prepared after the reports from the conference of 1925 and a report from Sir Frank Heath had been studied by the newly appointed Executive Committee: G. A. Julius, W. J. Newbigin and Professor A. C. D. Rivett. The Bill passed all stages in the House within a month and was assented to 23 June 1926. This Act established the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research. The first meeting of the Council was opened by the Prime Minister, S. M. Bruce, on 22 June 1926.

Key speeches

- Prime Minister W M Hughes speaking at the University of Melbourne, 22nd December 1915

- Prime Minister W.M. (Billy) Hughes, January 5th 1916 Conference in Melbourne that led to the gazetting of the Advisory Council in March 1916

- Prime Minister SM Bruce – 2nd Reading 1926 CSIR Act

Prime Minister W M Hughes speaking at the University of Melbourne, 22nd December 1915

He was glad to have the opportunity of placing before the gathering the views of the Government on this all-important matter. What he would say was what he considered was the business of Australia at the present juncture.

This was no party matter. It was national. We had to look upon this heritage of ours as a man looked upon his own heritage. We had to devise the best means of developing it; how to make the most of it so that the maximum of happiness could be derived for the people. It was obvious that what best served the people generally, best served the interest of a particular party. The truth that was obvious was not at once clear to many people who had often conceived the idea that their benefits should be promoted by a policy that neglected the welfare of Australia generally. That was their side of the policy, and it might for a time serve them, but they must look at the body politic and the body economic.

That was the function of science. It should act as a beacon of industry and guide its “feet through mazes of experiments.” It has to cure the existing diseases of the body economic and be its striking and producing power. It had been shown what potential wealth there was in this country, but we were practically in our swaddling clothes. Economically we were in our school days. It seemed to him that the policy of this country should be-must be-to take advantage of the plastic state of public opinion as we passed through the hour of trial. We had a great opportunity now.

There was now seething in the cauldron of this great war all the possibilities of a great and high civilization. It was one of the essentials of a real and satisfactory state of society that each man and woman should give a given amount of labour and this should be the maximum.

He did not fall in with all that had been suggested but he thought the idea of the national laboratory was the corner stone of the edifice. We could gather around us men of all branches of science and use their capabilities in an application to industry. Applied to agriculture and the secondary industries science would solve the problems that beset us.

With this institution fitted out for research work we would endeavour to open up new avenues for fresh industrial efforts. He believed in the power of science and business ability and the determination of our race to increase without limit the productivity of mankind. With scientific methods we could increase our productivity from fifteen to twenty per cent, and that applied to a million of money would mean a splendid investment.

It was perfectly clear that whatever was done in connection with the institution it must be done on sound lines. It would have to stand on solid rock though its topmost pinnacles pierced the fleecy clouds of the sky. There must be a combination of science and business capacity. As far as possible they must induce the co-operation of existing institutions in each State.

The Commonwealth Government would endeavour to co-ordinate the universities of the various States in this direction. It would not only co-ordinate but superimpose upon itself that which was necessary to create an institution similar to that in England, America and Germany. He gave the assurance that, as far as the Government could, it would give every assistance to make the project a success.

Of course the Government was not committed to details. The idea was plastic and would be moulded according to suggestions, which, in the fire of criticism, showed themselves best worthy. As far as possible they should avail themselves of the ability and service of scientific men in our own universities, but if necessary the strength of the staff could be reinforced from outside. He would certainly make it a point when he went to England to see the manner in which such laboratories carried on their business, and would do the same in America if he went that far. The Government without delay would take the necessary steps to give this institution a start.

Before the applause had died down Sir Thomas Anderson Stuart, unable to contain himself any longer, jumped to his feet, protesting that he hoped the Prime Minister’s ‘practical steps were not to be too practical’. He urged the Prime Minister to bide his time until some form of commission could inquire into the subject. Needled to retaliation Hughes threw caution to the winds.

With gesticulating arms and snapping fingers, reminiscent of his many battles in the House, he spurned Stuart’s suggestion. ‘He had lost faith in commissions’, he retorted, ‘no institution began better or ended worse.’

The roars of laughter that greeted this statement were soon to be changed to gasps of amazement when the Prime Minister announced: They should invite representatives of all the Universities to meet in Melbourne at an early date to consider the whole question and make suggestions. An institution was wanted that was capable of adapting itself at once to the circumstances of Australia.

The Government wanted the co-operation of science and business to further the ends of industry, and the Government was prepared to give 208 for every 20S worth. The Government would give £5,000, £50,000 or £500,000 if necessary. It was the best investment Australia could make. If it cost £500,000 they would be getting every penny of their money back again.

Prime Minister W.M. (Billy) Hughes, January 5th 1916 Conference in Melbourne that led to the gazetting of the Advisory Council in March 1916

“I have a profound belief in the destiny of this great country. Its future is bright with promise. To paraphrase the words of glorious John Milton, I see a puissant nation mewing her mighty youth, her fertile lands smiling with green pastures and waving corn, flocks and herds innumerable, and a free and virile people widely spread through her far-flung heritage.

I see her a great nation with outstretched arms encircling a continent, her feet lapped by the waters of two oceans, standing erect and gazing with clear and friendly eyes upon a world which has no cause to fear her and which she does not fear. Ours is a great and glorious heritage and we must defend it at all hazards. We must create conditions which will attract and maintain a virile population of whom a sufficient number must settle upon the land and I know of no way of settling people on the land except to make rural industry attractive, and to this science can lend a most powerful aid.

Science can make rural industries commercially profitable, making the desert bloom like a rose; it can make rural life pleasant as well as profitable. Science can develop great mineral wealth of which, after all, only the rich outcrop has yet been exploited. It can with its magic wand tum heaps of what is termed refuse into shining gold; and by utilisation of by-products make that which was unprofitable to work profitably. Science will lead the manufacturer into green pastures by solving for him problems that seemed to him insoluble.

It will open up a thousand new avenues for capital and labour, and lastly science thus familiarised to the people will help them to clear thinking; to the rejection of shams; to healthier and better lives; to a saner and wider outlook on life.”

Prime Minister SM Bruce – 2nd Reading 1926 CSIR Act

“This measure amends the Institute of Science and Industry Act 1920, and alters the constitution of the Institute of Science and Industry in several respects. The object of the Government is, not to create a great new centralised institute of research, but, for the benefit of both the primary and secondary industries, to bring about co-operation between existing agencies and to enlist the aid of the pure scientist, the universities, and every other agency at present handling scientific questions.

Every honorable member must consider it to be essential for Australia, with its splendid opportunities and difficult problems, to make every endeavour to bring to the solution of those problems whatever assistance science can offer. The only consideration which would deter honorable members from supporting this measure would be the feeling that it might lead to duplication and the overlapping of effort. I can assure them that the exact opposite will be the result; the bill will in no sense lead to a duplication of the efforts of the States, nor will it bring about any overlapping of scientific research in relation to our industrial or other problems.

What we propose is essential in a country such as Australia. Recent industrial developments prove that science can greatly assist in bettering the conditions of the workers and in bringing greater prosperity to our people. Those nations which to-day are progressing most rapidly industrially and commercially are enlisting its aid to an extraordinary degree.

The United States of America, I believe, lead the world in that respect. Their development has been amazingly rapid. Although the area of that country is slightly less than that of Australia, it carries a population of between 115,000,000 and 120,000,000 people, and yet its problem is how to obtain a sufficient number of workers to take advantage of the opportunities that present themselves. It is freely stated that America could easily absorb another 1,000,000 people to the advantage of the present inhabitants.

Seeking a reason for that amazing state of affairs, one realises what a great part has been played by scientific research. What strikes one most forcibly is that America’s efforts in the direction of scientific research are not limited to governments nor even to great associations of employers; individual employers are expending vast sums of money in attempts to improve their methods and generally to advance heir efficiency. Many individual manufacturing corporations maintain their own laboratories for experimental work, and employ staffs of trained scientists.

The largest concern is the Du Pont de Nemours Company, which has 250 chemists engaged on experimental work throughout the year. The Pennsylvania Railway Company has no fewer than 361 scientists employed in its testing laboratory, and the General Electric Company has 150. The first cost of the laboratories of these great manufacturing corporations or transport agencies was as high as £100,000, and the annual cost of some of them runs to a figure equally great. In all there are over 30 large laboratories belonging to individual firms, and a score of associations of manufacturers are engaged in work of a similar nature.

An extraordinarily interesting feature of the position in America is that, although these great research activities are conducted by individual firms or associations, almost without exception the utilisation of their discoveries is not confined to their particular business. These discoveries are made known to the industry generally on the principle that the improvement of its efficiency benefits all concerned. We can learn a great deal from America in that respect. The National Canners’ Association spends about £10,000 a year, and, connected with almost every industry in America there are associations which are carrying out research work for the benefit of their members. This covers a wide field of activity, and applies to lumber, paint, woollens, paper, refrigeration, dairying, cement, tiles, bricks, and almost every other product that can be mentioned.

It is notable, also, that American industries are co-operating with the universities. Great industrial enterprises send their problems to the universities to be investigated by pure scientists, and thus science is being applied to the solution of industrial problems. In addition, there are institutions of a public or semi-public character, like the Mellon Institute, which is associated with the University of Pittsburgh. In that institute there are no fewer than 80 highly-trained research fellows, who are carrying out work on selected subjects. Research fellowships are given to men who are selected by an industry, and those men go into the institute to solve, or attempt to solve, particular problems. Generally, they are afterwards absorbed into the industry, and, naturally, they raise its standard and assist its scientific development.

We have done a little in this country in promoting standardisation, but some persons have been appalled at hearing that the Government ought to spend £2,000 to assist the work. Within the limited means at its disposal, the Standards Association in Australia has done valuable work. But its activities should be extended. The Bureau of American Standards occupies buildings which cost £300,000, and its annual expenditure is about £460,000. All that money is being spent to bring about standardisation, which is regarded there as essential. One can readily realise how much can be saved by standardisation. We often fritter away time, money, and energy in producing ten articles when, if we had standardisation, one would do equally well. With standardisation we could reduce capital expenditure and overhead charges, and at the same time enormously increase production and efficiency. We must undertake research work, and the time is over-ripe for it.

I cannot now speak of all the activities of America, but I must mention the Carnegie Institute, which has an endowment of £4,500,000, and innumerable other institutions are carrying out similar work. Before the war Great Britain’s activities in this direction were not so great as one would have desired, but there has been, within recent years, with the more intense competition that has followed the war, a realisation of the need for research work. Machinery has been established, and is being rapidly extended, for carrying out valuable industrial and general research work.

The problem is being dealt with differently in Great Britain and America, and there is something to be learned from a comparison of the two methods. In America there is great activity, but no real co-ordination of effort. Great Britain is attempting co-operation from the top, and that should be our aim, for in this direction the Commonwealth Government can give particularly useful assistance. The Department of Scientific and Industrial Research in Great Britain was established in 1917, a year before the war closed, and a fund of £1,000,000 for the endowment of research associations was created by the Government, and has grown considerably since.

The expenditure of the British Government for the co-ordination of industrial research work, and for carrying out such work, has nearly doubled in the last three years, and during the current year will probably reach £550,000. The department is endeavouring to stimulate industrial research by manufacturers and associations of manufacturers, and has already promoted the formation of 25 associations of manufacturers to deal with different phases of industrial problems by bringing scientific methods to bear upon them. The British Government is also endowing university research work, and in 1924 made 258 grants, totalling £35,000, for that purpose.

Evidence of the development of thought on this subject in Great Britain is contained in the recent report of the Coal Commission. In dealing with the troubles in the coal industry the commission recommended that for a period of seven years an average sum of £50,000 annually should be set aside for scientific investigations into problems associated with the industry. Japan, which has experienced probably a more phenomenal industrial growth than any other country, is spending £300,000 on a national laboratory. The Indian Forestry Department is known throughout the world ; it is carrying out valuable research work relating to forestry and limbers. Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa – our sister dominions – are trying to do something effective in the same direction.

I shall not deal exhaustively with the bill, but I wish to say a word about the Institute of Science and Industry, which was created in 1920. The bill alters the basis of the original proposal. While the institute did not realise all the hopes entertained of it, it is wrong to suggest that it has done nothing. It has done quite a large amount of valuable work, but disappointment has been felt because the aims and ambitions of those who created it were probably too large to be realised in practice. The money provided for it was not sufficient to enable it to function successfully. I hope that on the present occasion we shall remove both these weaknesses in the scheme by not attempting to do too much, and by ensuring that for the next few years it will be impossible for the institute to be starved, and its activities rendered of no value.

I should like to refer to some of the work which the institute in its present form has done, because I think there has been a considerable amount of quite unjust criticism of it. I admit that it has not done all that was anticipated; but it has still done very valuable work, for which it is entitled to credit…

…It has done very valuable work in connection with the manufacture of paper pulp from Australian timber. It has done good biological work in the control of the “prickly pear”, and it has, I think, successfully solved the problem of “bunchytop” in bananas. Certainly the institute has not been a complete failure, as some people would suggest, but I think that every one recognises that the time has come when it should be re-organised and placed upon a different basis.

The Government, feeling that very strongly, last year summoned a conference of scientists, industrialists, and representatives of the commercial community. That conference was held in Melbourne, and made certain recommendations. The Government also invited Sir Frank Heath, who is at the head of the British Research Council, to visit Australia. He was in Australia for some three or four months at the end of last year and the beginning of the present year. He made a most valuable report to the Commonwealth Government, and to a considerable extent the proposals I am now bringing forward are based upon that report, which honorable members have had an opportunity of reading…

…The first alteration proposed is that the position of Director of the Institute of Science and Industry created by the existing act shall be done away with. The position as existing under the present act is to be completely altered. The whole of the control of the institute under the existing act is in the hands of the Director. By the new proposal it is contemplated placing the control of the institute in the hands of a Central Council, which will be the body advising the Minister. There will also be created six State committees…

…The Central Council will be composed of three members appointed by the Commonwealth Government, and the chairman of each of the State committees. These nine will form a body to advise the Government on all questions requiring scientific investigation. In addition to these nine members, additional members, whose assistance may be required because of their special scientific knowledge, can be co-opted. The reason for this is that it might be found that the Central Council did not include a representative of some particular branch of scientific research which it would be most desirable to have represented on the council. For example, there might be no biologist amongst them and it is essential that there should be a biologist upon an advisory council of this sort. Under the bill it will be possible for the Central Council to secure the assistance of a biologist, or any other scientist whose help it would be desirable to have…

…Of the Central Council of nine the three members appointed by the Commonwealth Government will form the executive. They will not be permanent, but part-time officials, but it is proposed that they should be paid fees, and should advise the Minister on all questions. It is not contemplated that the Central Council shall be called together more than once or twice a year. A period of the year when it will probably be called together will be the month of March, when the whole council will meet to prepare the estimates and programme for the forthcoming year. Apart from that annual meeting at which the general policy of the institute will be laid down, and the estimates for the forthcoming year prepared, it is not contemplated that the full council shall meet except in extraordinary circumstances, when some particular problem arises upon which it is necessary to arrive at a decision. In ordinary circumstances the work of the council will be carried on by the three executive members appointed by the Government…

…The Government is extremely fortunate in having obtained the services of Mr. Julius, an engineer, of Sydney, to act as chairman, and with him Mr. Newbigin, and Professor Rivett of the Melbourne University, who have agreed to act as representatives of the Government on the Central Council. That council will deal with the general programme, the budget, and the activities generally of the institute. It must determine the programme of work. It is not contemplated that research work will be carried out by the institute, but that it will be undertaken wherever the best facilities exist for carrying it out. For instance, the problem with regard to fuel waste would probably be best dealt with in Western Australia, and the Western Australian committee would be responsible for carrying out the work which the council determined should be carried out in that State. It is necessary that the institute should co-operate; but I wish to make it clear that research work wall be carried out in existing institutions, such as the universities of the States, and I am confident that we shall get the most cordial co-operation, from the States.

The universities are sympathetic, and we shall have their assistance, as well as the help of the industrial and commercial community generally. The State committees will have power to bring forward problems which they consider should be dealt with by the council, and where research work is being carried out in their own States, they will be responsible to the council for it. In this I think there is the germ of a scheme which should ensure the co-operation of the entire community…

…Three members will be nominated by the Governments of the respective States, from the staffs of their scientific and technical departments, and three other members will be what might be called pure scientists. Probably they will be members of the staffs of the State universities. These six members, with a chairman, to be appointed by the Governor-General, will co-opt two or three more so as to make each committee thoroughly representative and efficient. Several of the State Premiers have indicated that they are prepared to co-operate in the scheme, and to afford every assistance.

The actual functions of the State committees are set out in the bill. The purpose of the committees will be to advise the council as to the problems to be investigated. If a committee is directly interested in any problem affecting its State, it will investigate it, form its own conclusions regarding it, and make a recommendation to the council that research work upon it should be undertaken in the next year’s programme. It will also be the function of the State committees to keep in touch, and to cooperate with the various other bodies which may be interested in a particular work; to assist the council in organising the work carried out in the States, and to make inquiries and to furnish reports on matters referred to it by the council. If the executive requires further information from any State, it may utilise the State committee, and get the assistance required.

But when we embark upon a campaign of scientific research, unless we have trained scientists to carry out the work, we are not likely to get very far. It is regrettable that we have already lost the services of so many of the best men trained in our universities. Our objective, in launching this scheme, is to ensure that we shall have the assistance of men trained in Australia, and retain their services for this country.

The only other point to which I desire to refer now is the proposed change of the name of the ” Institute of Science and Industry” to ” Council for Scientific and Industrial Research.” We are making the change because we believe it will more truly indicate the functions of the new body. It is to be a council for scientific and industrial research. A further reason for the change is that the corresponding body in Great Britain is known as the “Department of Scientific and Industrial Research,” and the Canadian body is styled “The Advisory Council of Scientific and Industrial Research.” These bodies are receiving general recognition in other countries, and as we propose that the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research shall have similar functions, it is very desirable that the name should be similarly recognised for the character of its work…

…The council has given much consideration to immediate problems, and I think that the House will be interested to know what lines its investigations will take. It is considered that immediate investigation should be made regarding liquid fuels, cold storage, and the preservation of foodstuffs, forest products, animal diseases and pests, plant diseases and pests, and fruit-growing problems. All these matters are already receiving the consideration of the executive.

Certain estimates in regard to them will, probably, be embodied in the general Estimates for the forthcoming year, so that an immediate start may be made. Every one will recognize that liquid fuel, for example, is an important subject of investigation. Unfortunately we have no indigenous oil supply, and consequently are importing 90,000,000 gallons of petrol a year. There is a wonderful possibility before us if we can find a solution of the liquid fuel problem.

The institute up to the present has unquestionably suffered considerably owing to insufficiency of funds for its work. When an effort is being made to stimulate scientific research in relation to the problems of industry, and the best scientists of the country are showing a sincere desire to help to overcome our difficulties, it is most undesirable that their labours, which may have cost, perhaps, £10,000, should be lost because of the exigencies of a particular treasurer. The council might be on the brink of finding the solution of an important problem, requiring only an expenditure of £1,000 or £2,000 to complete its investigations, and its efforts would be defeated if the Treasurer of the day decided that no further money could bo made available to it.

To obviate such a position, it is provided in the bill that for the purposes of scientific and industrial investigation, in pursuance of this measure, there shall be appropriated from the Consolidated Revenue Fund the sum of £250,000. It is not contemplated to expend that sum in one year. That amount should carry the institute on for some time; but the money will be placed in a trust fund, where it will be available for the purposes of the council. To ensure that full parliamentary control shall be exercised over the expenditure of this money, it is provided that nothing shall be spent from the trust account except in accordance with estimates of expenditure approved by Parliament.

The council will meet and prepare its budget for the following year, putting down the amount it considers desirable for the research that is being done. Those estimates will be presented to the Minister, and if he approves of them they will be embodied in the general Estimates submitted to Parliament. If they are passed by Parliament, the money will immediately be made available out of the trust fund. That will avoid any possibility of a treasurer, through financial stress, curtailing the expenditure of the council at a time when it may need the full amount of its estimates to carry on its investigations. The sum of £250,000 will ensure that during the next three or four years there shall be a fund available for a serious effort to deal with our industrial scientific problems.

I am confident that the council’s work will in four or five years’ time be so obviously beneficial that no one will have the courage to attempt to destroy it. The bill should generally commend itself to the House. Every honorable member must be desirous that a serious effort, should be made, with the assistance of science, to solve the great problems now hampering industrial development. I believe that the bill provides for this. It will prevent overlapping and duplication, and with the assistance of our scientists, we shall achieve a result that may go far beyond what can be anticipated at present.

View the full Hansard transcript of the second reading on 26 May 1926.