Polymer banknotes

Australia’s introduction of plastic banknotes with optically variable devices (OVDs) was a world’s first and represented a paradigm shift towards a currency secure against forgery.

The research began in 1968 following a request from the Reserve Bank of Australia for a scientific solution to combat forgeries of the new decimal currency. CSIRO’s solution was to have a see-through panel and hologram embedded in the note and to use plastic. In addition to their inability to be forged, the new notes were also more durable, more environmentally friendly and less likely to carry dirt and disease.

The technical problems were solved within 10 years, but the conservative nature of the banking industry delayed release of these revolutionary notes until the Bicentennial year 1988. Securency International Pty Ltd, was formed in 1996 as a joint venture between the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and Innovia Films to market the technology.

By 1998 all Australian banknotes were issued in plastic and by 2009 Securency was exporting to 25 countries, with more than three billion polymer notes in circulation.

How it all started

In 1966, Australia converted from the Imperial system to a decimal currency with the issue of new state of the art security banknotes to prevent forgery. These notes were printed on quality paper which contained a watermark and metal threads, and used intaglio (raised print) printing. However, in less than a year quality forgeries of the $10 note appeared. The Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) at the time, Dr HC (Nugget) Coombs, decided to turn to science to overcome this problem. He was convinced that science should be able to put a bigger distance between what the forgers were so easily able to simulate and what the bank could produce.

In 1968, a ‘think tank’ was arranged, at Thredbo, NSW, for a few scientists from CSIRO and the universities to come together and discuss the challenge. The invitations to the initial meeting were incidentally dated April 1st, and they indicated that discussions were to be on ‘some aspects of banknote printing’. As Dave Solomon recalled some 42 years later:

A key point made at the meeting by a representative from Kodak Australia was that if the new banknotes could be photographed they could also be printed and forged.

Early development

Dave Solomon was invited to attend this meeting and, together with Dr Sefton Hamann, decided that the way to challenge the forgers was to prevent them making printing plates by having in the note a device that could not be photographed, the so called Optically Variable Devices (OVDs). These are defined as any device that changes its appearance when something external to the note is changed, such as the angle of viewing, temperature, etc. As Dave recalled:

The challenge of beating the camera was taken up and led to a range of what were to become known as OVD’s, optically variable devices. These are defined as any entity that changes its appearance when something external to the note is done. For example: if the note is held between the fingers the pressure causes a colour change; if the note is rotated a colour change occurs or an image moves across the note; if the note is taken from a wallet it changes colour etc. These OVD’s could not be photographed and hence made it difficult to forge.

We produced these devices in large quantities to demonstrate the practical nature of the concept. We built a production plant in secret and printed a design provided by the RBA ‘ birds in flight ‘ using our plastic film. However the number of ideas was beginning to confuse the Reserve Bank and a freeze was put on further designs. So we focussed on Diffraction gratings (Holograms), Moire interference patterns, photochromic compounds and a label. The latter was detectable by a machine.

Dave then made the massive leap to replace traditional paper with a plastic film. The presence of a clear area alone would force the forger to use plastic and no commercially available film was available ‘ Dave’s group made their own and it was unique. The laminate which CSIRO developed, when opacified, could be printed conventionally, after which the security features were applied. The most notable features were the see-through panel and hologram.

Testing the new notes

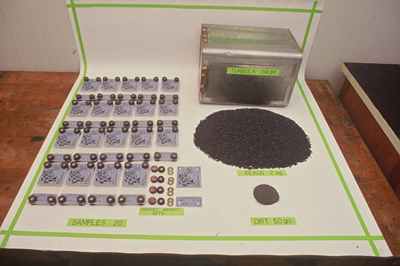

At one stage Dave’s team numbered 31 staff. In secret, they built a pilot production line and produced the equivalent of 50 million banknotes and 1.25 million OVDs to prove to the Reserve Bank that these revolutionary ideas were practical. This was necessary to convince the Reserve Bank that these innovative notes could be produced economically.

Testing was a particular challenge: it is not possible to field trial a banknote. One such test was the so called Turbula, or Tumble Test, which involved placing weights in the corners of the notes and then tumbling them in a kerosene drum containing controlled amounts of synthetic dirt (carbon black), abrasive materials (polypropylene beads) and even artificial sweat. This was remarkably accurate in predicting the field performance of the notes, and found use in later quality control.

Unredeemable dominations ‘ the $3 and the $7 notes

Partly as a joke, but also for security reasons in case their experimental notes were lost, Dave’s team printed $3 and $7 test notes, denominations not encountered in the Australian currency system, on their pilot production line. The two circles on the note indicate the positions where the OVDs would be inserted and subsequently protected by clear films of plastic on either side.

First release in the Bicentennial year 1988

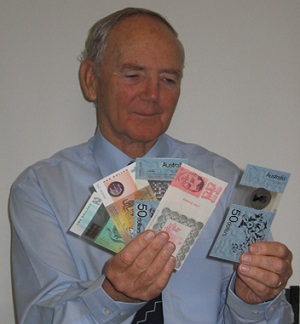

The longer life of the plastic notes more than offset the slight increase in cost and eventually in 1988, the Governor of the Reserve Bank at that time, Mr RA Johnston AC, decided to release a limited edition for the Bicentennial year, the next best thing to a field trial. The commemorative bicentennial $10 note was the world’s first plastic film note with OVDs.

For Dave Solomon and his team, it was very satisfying to see the notes used and be accepted by the public. By 1998 all Australian banknotes were issued in plastic and Australia became the first country in the world to convert from a paper-based banknote currency to a polymer-based one. The savings over paper notes at the time were estimated to be more than $20 million per annum.

Why 21 years from the first meeting to release?

The technical problems were solved in principal in about 10 years, but the ultra conservative nature of banking significantly held up the eventual release of these revolutionary polymer banknotes. A massive cultural change was needed in the Reserve Bank to move from a position of importer of technology to a world leader.

One of the moments of despair for Dave Solomon during the development of this project was when the Reserve Bank took over and tried to carry out the project with staff not trained in development. The relief was the courage of the new Governor, Mr RA Johnston AC, who listened to Dave and decided to recruit engineers and scientists.

Commercialisation

Furthermore, the commercialisation was always an issue. The Bank belonged to bankers clubs which shared information to beat the bad guys, the forgers. Some senior bank staff wanted to share the plastic note technology at no charge to the world banks. This was a constant point of argument with Dave and eventually the CSIRO position was accepted ‘ that the technology should be offered at commercial rates.

These days Securency International Pty Ltd handles the commercialisation and export to 25 countries.

A world class Australian invention

It is interesting how many people do not realise that the banknotes they use everyday are an Australian invention. As Dave recalled:

I was in a store with a friend one day, when he told the sales assistants that I had invented the banknotes. They didn’t believe him!

For his role in the discoveries and subsequent leadership of the team responsible for the production of the world’s first plastic banknote, Dave Solomon has received many awards, including:

| 2008 | Society of Plastic Engineers (Australia and New Zealand) Innovation Award |

| 2006 | Victoria Prize for Science |

| 1994 | Clunies Ross National Science and Technology Award |

| 1988 | The Australian Bicentennial Science Achievement Award |

| 1988 | Ian William Wark Medal and Lecture, Australian Academy of Science |

He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society London (FRS), in 2004 where the banknote project was part of the nomination case and made a Member of Order of Australia, for contributions to science and technology, particularly in the field of Polymer Chemistry in 1990.

Source

- Solomon DH, 2009, Personal communication.

- Banknote Production: Polymer Technology (Reserve Bank of Australia)

- The records of currency note research and development project, CSIRO, Division of Chemicals and Polymers (1968-1990) / prepared by Rod Buchanan, Gavan McCarthy and Oscar Manhal.

- Solomon, D. & Spurling, T. (2014). The plastic banknote: from concept to reality. CSIRO Publishing