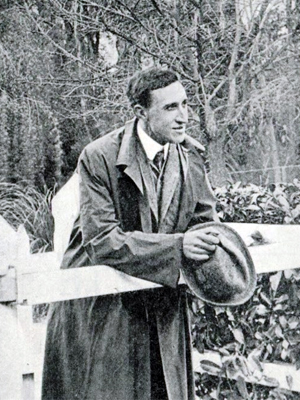

Thorburn Brailsford Robertson (1884 – 1930)

Thorburn Brailsford Robertson was born in Edinburgh, Scotland on 4 March 1884, the only child of Thorburn Robertson, insurance clerk and actuary, and his wife Sarah-Ann, nee Brailsford. His mother took him to South Australia in 1892 to join his father who worked for a mining company at Callington. He was educated at a private school (the Misses Stantons’ School, New Glenelg), and by a private tutor up untill the time he got his BSc and was always recognized as a brilliant student, with an original turn of mind. He entered the University of Adelaide in 1902, studying physiology (BSc, 1905) under Professor (Sir) Edward Stirling. Robertson showed exceptional ability in abstract thought and considered a career in mathematical physics, as a result of Professor (Sir) William Bragg’s teaching.

In 1905, he became assistant lecturer in the physiology department at the University of California, Berkeley, USA, led by the famous Jacques Loeb. Under his influence Robertson developed a physico-chemical outlook and research skills which he always retained. Idealism permeated all his thinking and, courageously, he attacked and later refuted many doctrines then accepted. He earned a PhD from Berkeley in 1907 and then a Doctor of Science from Adelaide in 1908, an extraordinary achievement at the age of 24.

In 1910 was promoted to the position of Associate Professor of physiological chemistry and pharmacology at Berkeley, becoming full professor in 1917. The following year he accepted the chair of biochemistry at the University of Toronto, Canada, but moved to the chair of physiology at Adelaide in 1919 on Sir Edward Stirling’s retirement. The decision was unusual in that Robertson had gained by this time international prominence in biological research and the move meant the sacrifice of opportunities which Adelaide lacked.

At the University of Adelaide

The ensuing eleven years saw enormous achievements. Robertson revealed organizational abilities, flair for research and tremendous energy by establishing the modern discipline of biochemistry in the university’s small medical school. He had been appointed as professor of physiology, but in his publications in 1922 he described himself as professor also of biochemistry. His was the first professorial appointment in Australia to embrace biochemistry. His allegiance to it, rather than human physiology, resulted in his becoming, in 1926, professor of biochemistry and general physiology, with (Sir) Stanton Hicks teaching the clinical aspects of human physiology and pharmacology to medical students.

Robertson was a tall, popular man who, despite his drive and leadership was gentle, tolerant and understanding of colleagues. An excellent lecturer, he was foremost an inspired and inspiring investigator who greatly influenced the development of a research outlook in the medical school. He modernized the teaching of his subjects to both medical and science students, setting up new curricula including an honours course in biochemistry, the format of which remained until 1952. He was the driving force behind the establishment of the Darling Building at Adelaide University, and played a crucial role in its detailed planning. The building, opened in 1922, housed the disciplines of physiology, biochemistry and histology. He was also a major force in the formation of the Animal Products Research Foundation of the University of Adelaide and of its graduates’ association.

To promote the interaction of clinical medicine and fundamental science, he co-founded the Medical Sciences Club of South Australia in 1920 with Professors (Sir) John Cleland and Frederick Wood Jones and in 1924, in conjunction with the club and Professors Cleland and Wood Jones, established the Australian Journal of Experimental Biology and Medical Science. The journal’s ninth volume (1932) includes a list of Robertson’s publications.

He played a pivotal role during the early 1920s in establishing insulin manufacture in Australia. It was manufactured in the Darling building at the University of Adelaide for the first time in Australia (under license from the insulin committee of Toronto University), for use on diabetic patients in the (Royal) Adelaide Hospital, in 1923, within a year of Banting and Best’s published discovery of the hormone and its relationship to diabetes. In 1924, he had manufactured 40,000 doses from pancreas provided by the Metropolitan Abattoirs’ Board.

He was a pioneer of the physical chemistry of proteins and devoted much of his research to the problem of growth. He discovered and patented the substance ‘tethelin’, which stimulates growth, and was found to be very effective in the treatment of ulcers of long standing, and slow, healing wounds. A trust was formed at the University of California to manufacture tethelin, with the income from it devoted to scientific research. His work into animal growth represented a major contribution to agricultural science and industry in Australia and he was recognised as one of the foremost authorities in the world on animal nutrition. His experiments attracted wide-spread attention wherever the scientific feeding of flocks and herds has been studied in conjunction with soil values.

At CSIR

In 1927 the Commonwealth Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) invited Robertson to form and direct the work of a Division of Animal Nutrition, located in the university. He thus was the first Chief appointed to a CSIR division, being appointed on the 1 February 1928, beating Bertram Thomas Dickson, the Chief of CSIR Economic Botany, by 26 days. Field stations were established across Australia. In addition to his role at CSIR he remained professor at the university but gave up most of his teaching concentrating on experimental work on growth, and the demands of founding a new national research laboratory.

Robertson enjoyed music and art and was well read in philosophy, history and classical literature. He pioneered many avenues of thought, publishing some 170 papers, textbooks, essays on the philosophy of science and research, even children’s storybooks. His first published book was the ‘Universe and the Mayonnaise and Other Stories for Children’, which appeared in 1914. Four years later he issued ‘The Physical Chemistry of the Proteins’, following this in 1920 with ‘Principles of Bio-Chemistry’, which ran into two editions. He despised the commercialism sometimes associated with scientific research. His interest in the mechanisms of growth and longevity in animals culminated in the publication of ‘The Chemical Basis of Growth and Senescence’ (1923) and earned him a description as Australia’s first experimental gerontologist. Besides these works, he contributed many papers to the Journal of Physical Chemistry and to physiological, and bio-chemical journals.

He was a member of:

- the American Association for the Advancement of Science

- the American Association for Cancer Research

- the American Physiological Society

- the Animal Products Research Foundation

- the Australian National Research Council

- the Biochemical Society (England)

- the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine, New York

- the Medical Sciences Club of South Australia

- the Royal Society of South Australia.

Untimely death from influenza

Robertson contracted influenza in 1929-30, but continued working in the laboratory despite extreme summer heat. His health was undermined by overwork, and the fact that he had been an asthmatic from childhood. He died on 18 January 1930, in the prime of life, at Warringa private hospital, Glenelg, after having been taken from his home at Mount Lofty. His ashes were scattered in Waterfall Gully, a part of the Adelaide foothills which he had loved. His wife and children survived him; his sons pursued medicine and science.

His death was both untimely and a genuine loss to the University of Adelaide. He was widely regarded as having possessed a rare capacity both as a teacher and researcher. A stained-glass window designed by Edith Lungley, overlooks the rear stairway of the University’s Mitchell Building and remains as a permanent memorial to this remarkable scientist and author ‘who dared to follow the consequences of a mechanistic science to the rules of human conduct’.

This image is also reproduced in the Brailsford Robertson award introduced in 2001 by CSIRO and the University of Adelaide to encourage collaborative research in areas of health identified as strategic priorities by CSIRO and the University of Adelaide.

Fellowships

| 1926 | Foreign member, Reale Aceademia Nazionale in Italy, the oldest academy of science in Europe. He was elected to the section of biological science, to which one foreign member is elected annually. |

| Fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science | |

| Fellow, Royal Society of South Australia |

Sources

Rogers GE, 1988, Robertson, Thorburn Brailsford (1884–1930), Australian Dictionary of Biography Volume 11 (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/robertson-thorburn-brailsford-8239)

‘Robertson, Thorburn Brailsford (1884–1930 ), Obituaries Australia, http://oa.anu.edu.au/obituary/robertson-thorburn-brailsford-8239

‘Thorburn Brailsford Robertson -Pioneer of insulin manufacture in Australia’, Lumen, University of Adelaide Magazine, Summer 2006 – http://www.adelaide.edu.au/lumen/issues/16381/news16396.html

T. Brailsford Robertson [http://auniarch.wordpress.com/2011/10/28/t-brailsford-robertson-correspondence/]