Prawn fishing industry in the Gulf of Carpentaria

With the closure of the humpback whaling industry in Australia and New Zealand, alternative fishing ventures were considered in the early 1960s. CSIRO’s Geoff Kesteven suggested that the Gulf of Carpentaria could prove to be a source of prawns comparable in value to the Gulf of Mexico.

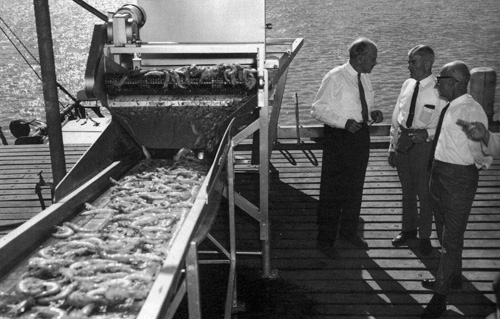

On the 26 July 1963 a survey of the fishing potential and other factors in the Gulf of Carpentaria commenced. It was a difficult venture, led by Ian Munro. The Gulf is a hazardous and inhospitable place; the facilities at the time were minimal; the men worked under trying conditions and considerable hardship; and the initial results were disappointing. Then finally, while working some 32 kilometres offshore they tasted success with the discovery of a large school of prawns.

The survey closed on August 1965 having established that the Gulf of Carpentaria could sustain a successful prawning industry for Australia. It has and while experiencing boom times followed by the effects of overfishing, is now on a sustainable footing. In 2009, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations reported that Australia’s wild-caught prawns came from the best managed marine fisheries in the world as a result of the application of a bio-economic model that sets harvest levels that maintain productive prawn stocks while maximising fishery returns.

The model was developed by the CSIRO Wealth from Oceans Flagship, the Australian Bureau of Agriculture and Resource Economics and the Australian National University.

The Gulf of Carpentaria is an inhospitable place

The Gulf is a 300 000 square kilometre bite out of the north-east coast of Australia. It is an inhospitable place that discouraged interest from the time the earliest Dutch explorers sailed into it in 1623 and named it for the then governor of the Dutch East India Company, Pieter Carpentier. Its shimmering green and often muddy waters, bordered by mangroves merging into marshes and salt pans, were a breeding-ground for the fever that virtually wiped out the first settlement at Burketown, 242 years later. In the summer wet season 500 millimetres of rain can fall in a day and the humidity is intolerable.

For many years the only activities to disturb the Gulf’s torrid lethargy were the discovery of copper at Cloncurry, a brief flurry of gold-mining at Croydon, and the taking up of isolated cattle leases the size of English counties.

The possibilities of a prawn industry discussed

It might have remained so for a lot longer but for an informal lunch in the elegant surroundings of The Chalet restaurant in lower Pitt Street, Sydney, in September 1962. The host was Bob Mostyn, Chairman of Craig, Mostyn and Co. Pty Ltd, owners of a fishing and exporting business. The humpback whaling industry had just closed down in Australia and New Zealand, and during the meal, conversation inevitably drifted to the possibility of alternative ventures. Mostyn mentioned he had sent two prawn trawlers to the Gulf early that year, but they had managed only limited catches of juvenile prawns and the prospects seemed dim.

One of the lunch guests, Geoff Kesteven, Assistant Chief of the CSIRO Division of Fisheries and Oceanography, was optimistic. He said he believed the Gulf had a vast, untried potential as a prawning ground. As Mostyn recalled later: Kesteven was an enthusiastic battler for Australian fishing. The suggestion for Gulf prawning really came out of his fertile brain. If we hadn’t started then it might be dead even today.

Events moved quickly. Within a month the Queensland Treasurer, Tom Hiley, wrote to the Commonwealth Government stating that Craig, Mostyn and Co. plus three other companies were interested in Gulf prawning and that Kesteven had given his private opinion to the Queensland fisheries authorities that the continuing haul of prawns from the Gulf could equal Australia’s present production

In November 1962 Mostyn wrote to both the Commonwealth and Queensland governments saying his company proposed to start fishing and processing immediately after the coming wet season. Karumba, on the south-eastern corner of the Gulf, appeared the most suitable operations centre. He wrote: In our opinion it would be appropriate to conduct a survey of fishing potential and investigation of other pertinent factors by CSIRO in conjunction with fishing operations

The following week a meeting was called of representatives of government departments, fishing companies and CSIRO. The official minutes reported that: Dr Kesteven drew an analogy between the ecology of the Gulf of Mexico and the Gulf of Carpenteria and stated that he saw no reason why an extensive prawn resource should not exist in the Gulf of Carpenteria

On what he claimed were conservative assessments of the experience in the Gulf of Mexico, he estimated that an annual take of up to 26 million pounds (112 000 tonnes) of raw prawns might prove to be possible.

The survey begins with lots of problems

In conjunction with Craig, Mostyn and Co. Pty Ltd, the Commonwealth Department of Primary Industry, the Queensland Department of Harbors and Marine, and CSIRO reached agreement on the survey in May 1963. The survey party comprising scientists and technical officers from CSIRO and the Queensland Department was led by Ian Munro, a principal research scientist of the CSIRO Division of Fisheries and Oceanography. The party flew into Karumba on 26 July and started work three days later with the arrival of the survey vessel Rama. Five small Mostyn-sponsored trawlers and an independent boat, Kestrel, arrived the same day.

Karumba, an overseas flying-boat service base before the war, consisted in 1963 of two government houses and ‘The Lodge’ which was run by Ansett Hotels to cater for the small number of tourists visiting the area. Once a week, if weather permitted, an Ansett DC3 flying the famous ‘station run’ landed on a grass strip, which first had to be cleared of goats. Normanton, a sleepy little town on a broad red-gravelled main street, was 80 kilometres away over a dirt road. In the ‘wet’ the road disappeared under grass three metres high and became impassable. It had been established as the port for north-western Queensland in 1867.

The survey team’s headquarters, home and laboratory was a small cottage on stilts, rented from ‘The Lodge’. For two years up to eight men at a time lived and worked in these cramped conditions for three-month stints. The stress was to prove too much for some of them.

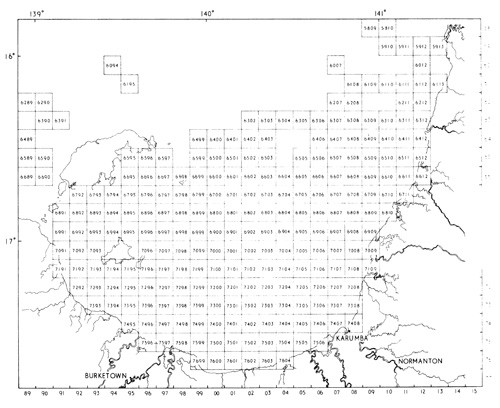

The south-eastern survey area represented about 8 per cent of the Gulf. All of it was within the 20-fathom (365-metre) depth contour and three-quarters was less than 10 fathoms (18 metres). The two existing charts were based mainly on soundings taken by Matthew Flinders in 1801 and Commander Stokes in 1841. Mirages appeared to lift the coastline so that boats could be several kilometres further out to sea than their crews believed. Even in 1965 the Australian Encyclopaedia described the Gulf as a place where navigation is hazardous except for skippers of small craft with extensive local knowledge

The survey vessel Rama was a chartered 15-metre commercial prawn trawler which cruised at 8 knots. She was designed as a day-trip trawler and not for prolonged surveys in the tropics. Her fish holds were not refrigerated and accommodation was poky and poorly ventilated with no lavatory or washing facilities. A small awning gave only limited deck cover from the blazing sun. Yet for six days at a stretch her crew (skipper, mate, observer) hauled back and forth over the lonely waters of the Gulf. Her only navigation aids were a steering compass and an unsophisticated echo-sounder.

Her shakedown cruise was used to educate the crew in the apparently odd requirements of scientists and to show technicians the procedures for sampling prawns and benthos (flora and fauna from the ocean floor). They also had to learn the drill for collecting water samples and bottom-sediment samples and for observing temperatures and other environmental data.

The original survey grid was ruled out in neat squares of 6 minutes latitude and longitude to give a statistical coverage by area and season. But tides were stronger than expected and forced trawling traverses out of alignment. A 44 gallon drum of formalin was ordered to preserve samples but only a half-empty 4-gallon drum was delivered. Shallow trays of ice made in ‘The Lodge’ cold room only just saved the samples from completely putrefying.

The situation on shore was no better. Munro later recalled that:

Instead of a standard laboratory set up with gleaming chrome and stainless steel plumbing, there was only the bare earth and the shade of the cottage overhead. The only furnishings were a makeshift bench fashioned from a discarded door and a sheet of galvanised iron. Putrefying samples being processed here nauseated the biologists and attracted swarms of blowflies.

Morale was not good. The Queensland fisheries men and the CSIRO men found themselves working under different salaries and awards for identical work. This, and boredom, caused friction and dissatisfaction. Tempers were shortened by high humidity and mosquitoes during the ‘wet’, and stifling heat and sand flies during the ‘dry’.

There was no recreation – swimming was ruled out by sea snakes, crocodiles and sea wasps – and in ‘The Lodge’ bar a bottle of beer cost three times as much as it did in Sydney. Munro had to play diplomat and judge to keep the team together. He cheered them with his confidence in the ultimate success of the survey.

Conditions improve but results disappointing

Then, slowly, working conditions began to improve. Munro drove a utility truck from Brisbane loaded with building materials that helped the team build a rough-and-ready, fly-proof laboratory. A reference collection of preserved organisms – fishes, prawns, sponges, corals, shells, starfish was assembled. The truck made it possible to visit Normanton for weekly shopping trips.

An ice-making machine meant Rama could undertake longer trips and return with better specimens. (Kestrel made a couple of forays and a fleet of large trawlers arrived from Western Australia on a private survey. None of them located anything promising.)

In December the wet season started, flooding the country around Karumba. Rama ran into eight weeks of troubles. She had to run for cover in two cyclones, was damaged by fire, and had to be located by plane and towed 160 kilometres to port when her engine broke down. Lightning damaged her radio and magnetised many of her metal parts, making her compass useless. These parts had to be replaced and a new compass fitted. However, by early May a shore transmitter had Rama in constant contact; it became possible to plan regular operating schedules and modify them according to conditions and new information.

First success in unexpected location

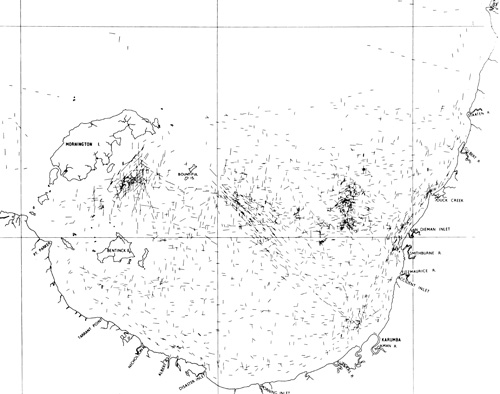

Although Rama had taken some prawns in nearly every trawl, including commercially valuable species such as banana, blue-leg, tiger and Endeavour, catches were disappointingly small. The big hope had always been banana prawns, but it was May before the first important catch of this species was made. The catch was a complete surprise. Rama was working 32 kilometres off shore in the middle of the survey area: previous experience in Bundaberg indicated banana prawns were most likely to be caught within 3 kilometres of river mouths.

A department of Primary Industry gear expert, Peter Lorimer, was on board Rama experimenting with the echo-sounder. About midnight some interesting shadows appeared on the screen – a school of banana prawns. Rama swung through the school twice. The first time she lifted 270 kilos of banana prawns and the second time 72 kilos of banana and king prawns.

Back at Karumba the radio crackled and Munro answered the call sign. Rama’s skipper called: You owe me that magnum of champagne!

The prawns were caught in a huge, massed ball emerging from the ocean floor in a ‘boil’ of mud. Experience was to show that these balls could weigh 4 tonnes and more. Spotting ‘mud boils’ from light aircraft became a ready way of fixing catch areas.

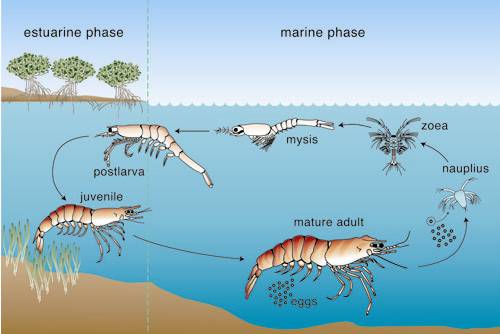

Scientists deduced that banana prawns in the balling stage were mating, but not necessarily spawning. Schooling was likely to occur in depressions on the ocean floor that marked the outward flow of rivers. Spawning apparently occurred in deeper waters during summer and after the eggs hatched the larvae rose to the surface, migrating towards the coast as they developed further and entered river estuaries as post larvae. Here they settled, developing into juvenile prawns, feeding and growing for three to four months. As the next crop of post larvae entered the estuaries, the now adolescent prawns began an off-shore migration. In the survey area it was found that males matured before females. They were adult, with a carapace length of 22 millimetres, before they reached the sea. Females reached maturity at the ocean mating grounds, with a carapace length of over 31 millimetres.

Much of the information for this came from surveys made in the mangrove prawn nurseries from a 4-metre outboard. Juvenile prawns were caught and dye-marked in cages.

Survey concludes and a new fishery is born

In March 1965 Rama and the Mostyn-owned Toowoon Bay began following migrating prawns seawards from the river estuaries, trying to locate the balled schools. They succeeded, with three lifts of 675 to 850 kilos in depressions out from Smithburne River. They also found a relationship between schooling behaviour and periods of minimal tide flow. Excitement was intense. Two commercial trawlers joined the team. The four vessels between them lifted more than 5 tonnes of banana prawns, using the scientists’ predictions of time and place. Other good catches followed.

The vessels now began testing to see how long the prawns were likely to be available. But they were hampered by bad weather. Engine trouble forced Toowoon Bay to drop out. Others were caught in a gale and one had to be found by an air-sea search. On the 122nd cruise, during the 2 234th trawl, Rama broke down. It was 29 July 1965, the second anniversary of the day Rama first wet her nets in the Gulf, and two days before the survey was scheduled to end.

The weather was foul and the crew had had enough. On shore there had been an increasing turn-over of staff. As Munro recalled: People just couldn’t stick it out. In places like that people go troppo in some degree. Some nice troppo, some nasty troppo.

The Karumba station closed down on 13 August 1965 and the team returned to civilisation. The survey had been remarkably cheap – a total outlay of about $300 000 plus scientists’ salaries and equipment. The two year survey of the waters of the Gulf of Carpenteria revealed the existence of valuable prawning grounds and opened up a major Australian fishery.

A fluctuating industry

In the decade that followed the size of the Gulf prawning fleet and its catch varied widely from season to season. During the 1970s it never fell below 2 500 tonnes: nearly 300 trawlers lifted 3 690 tonnes live weight of prawns – about 90% of them banana prawns, in 1971 and in 1974 a record catch of 6 415 tonnes of prawns was recorded.

For a time the Northern Prawn Fishery flourished. However by the 1980s the Gulf was being seriously over-fished and the federal Government funded a vessel buy-back scheme to reduce the amount of prawns being caught. Despite this, tiger prawn stocks had still not recovered by the 1990s.

Sustainability in the 21st century

By 2009 things had improved considerably leading to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations reporting that Australia’s wild-caught prawns came from the best managed marine fisheries in the world. In its report, A global study of shrimp fisheries, the FAO praises Australia’s Northern Prawn Fishery (NPF) as a global model of fair, flexible and accountable management.

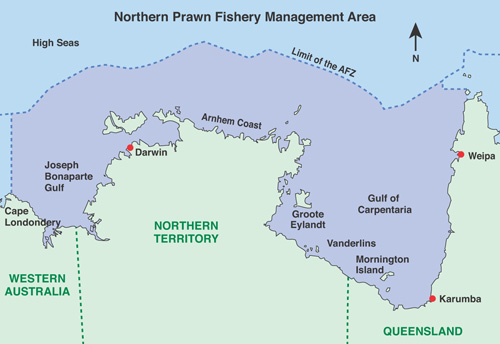

The $64 million NPF harvests banana prawns and tiger prawns from a fishing ground that extends from Weipa in far north Queensland to Cape Londonderry in northern Western Australia.

The reason for the turn around was the application of a bio-economic model, developed by CSIRO, the Australian Bureau of Agriculture and Resource Economics and the Australian National University, to set harvest levels that maintain productive prawn stocks while maximising fishery returns. As Senior CSIRO Wealth from Oceans Flagship scientist, Dr Cathy Dichmont, stated: The Northern Prawn Fishery is among the first major fisheries in the world to fully embrace both economic efficiency and environmental sustainability in an operational management system

Research on the model was funded by CSIRO and the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, and supported by the NPF and the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA). The CEO of NPF vessel operator Austral Fisheries, David Carter, commented:

Continuing collaboration between the industry, scientists and fishery managers should ensure the NPF’s future success. Extensive research in the NPF has helped us address market downturns, over-fishing of tiger prawn stocks, and the environmental impacts of fishing. Annual surveys designed by CSIRO monitor prawn stocks and bycatch (non-target species), and science-based management strategies underpin a profitable and sustainable way of fishing.

For the development of a combined biological and economic model to guide the management of Australia’s Northern Prawn Fishery in a way that ensures industry profitability and a vigorous fishery resource, Dr Catherine Dichmont and the northern fishery bio-economic team (CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research) were awarded a CSIRO Medal for Research Achievement in 2009. Their approach has won international acclaim as a global paragon of fishery management.

Sources

- McKay A, 1976, ‘Prawn harvest in the Gulf’, In: Surprise and Enterprise – Fifty Years of Science for Australia, White F, Kimpton D (eds), CSIRO Publishing, pp.44-47.

- Dichmont CM, 2009, Personal communication.

- Prawn fishery applauds its pioneers, 2005 (Media Release)

- Prawn fishery seeks three tiers of sustainability, 2005 (Media Release)

- Raw praise for Australian prawn fishers 2009 (Media Release)

- Maintaining ship-shape northern marine ecosystems (Overview – Research)

- Northern Prawn Commemorative Posters [PDF 8.6 MB]