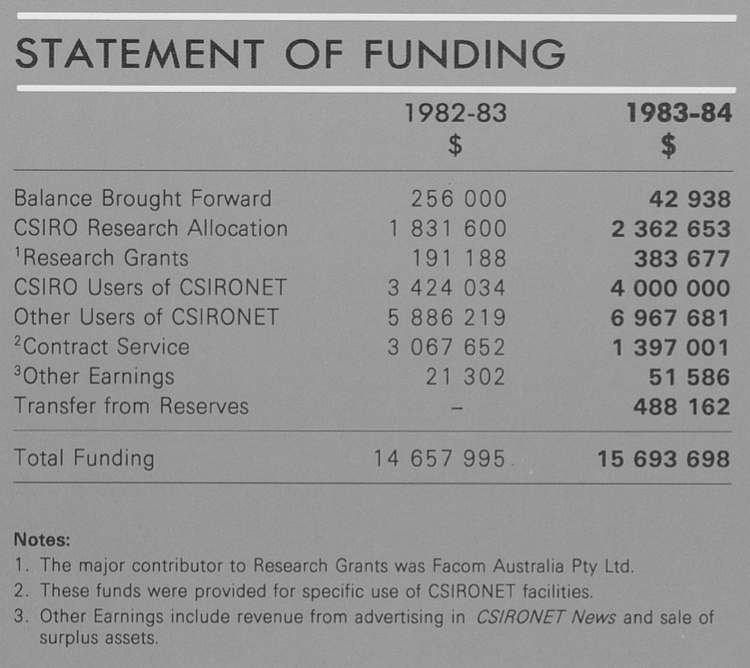

CSIRO Computing History, Chapter 3

Division of Computing Research and Csironet – growth. 1967-1980s

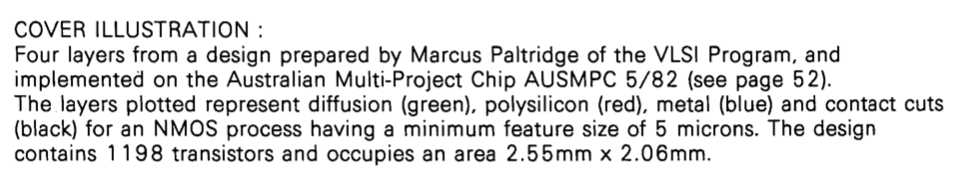

Last updated: 7 May 2025: added FACOM M-190 brochure.

19 Feb 2024: added 1975 Future Prospects paper in the 1974-75 section.

Updated: 17 Jul 2023: added links to chapter 3b.

Robert C. Bell

previous chapter — Computing History Home — next chapter

Contents

| 1967 – DCR, DAD, Document Region management, disc |

| 1968 – DCR, widening applications, displays, more branches, evolution of on-line storage and management, first PDP, interactive editing (FRED), teletypes, first remote access, Trevor Pearcey seconded to CDC |

| 1968-69 – DCR, displays, appeal for expansion, Perth branch |

| 1969-70 – DCR, wide-area network=CSIRONET, access to CDC 6600, multi-user disc access, interactive job scheduling, computer-to-computer link, visualisation |

| 1970-71 – DCR, two-bank DAD, growth in on-line storage demands – management, Townsville office, job submission via telex, start of network project, interstate lines, PDP-11s, text processing, small computers, DAD exported |

| 1971-72 – DCR, CSIRONET in operation, PDP-11 nodes at branches, Rockhampton branch, virtual Document Region, reentrant FRED, improved reliability, Claringbold acting chief |

| 1972-73 – DCR, Cyber 76 announced and arrives, Margaret Thatcher visits, DR retention periods and becomes and HSM, extension of CSIRONET to provide local nodes, TED replaces FRED – boxes |

| 1973-74 – DCR, Cyber 76 in service: links, porting apps, permanent file management; CSIRONET: 30 nodes, delays in lines for network, Remote Access Group; AI, 3200s removed, building extension announced |

| 1974-75 – DCR, COMp80 in service: microfiche, image processing, Hobart branch, Cyber 76 low MTBF, non-CSIRO usage reaches 40%, CSIRONET: 50 PDP-11 nodes, 48 kbit/s trunk lines, custom host-network interfaces |

| 1975-76 – DCR, building extended, Fernbach report, non-CSIRO usage 50%, CSIRONET: 43 nodes, multi-host development, peripheral driving, NODECODE exported; preparation for 3600 end: Cyber 76 and node enhancements |

| 1976-77 – DCR, Chiefs: Claringbold replaces Lance, 3600 nearly phase out, COMp80 direct connect, typesetting, standalone Cyber 76 system, Ed replaces TED |

| 1977-78 – DCR, 3600/DAD/Document Region decommissioned; 2500 users, Birch report: cost recovery and maximising usage, rationalising Divisional computing, rationalising government-supported scientific computing; improved reliability, CSIRONET: 68 nodes; new computer hall in preparation |

| 1978-79 – DCR, restructure, FACOM joint development project; M-190, NSC Hyperchannel and ATL installed; low-priority charges, improved resiliency, Ed libraries, CSIRONET: distributed services, network links to USA, 96 nodes; new computer hall under construction, visitors to User Assistance |

| 1979-80 – DCR, typesetting, new systems – lower Cyber, ATL, FACOMS; building delay; CSIRONET: 102 nodes, inter-networking, Mail, microprocessors |

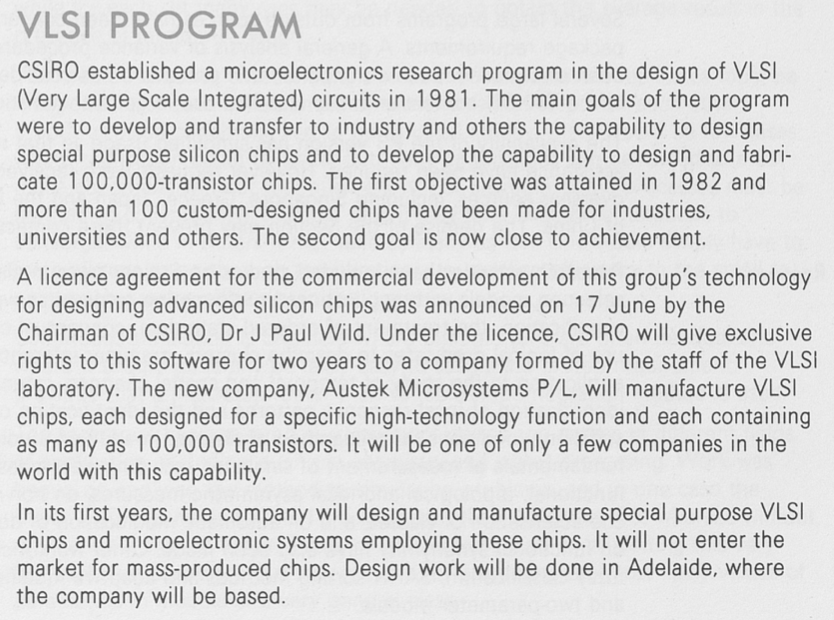

| 1980-81 – DCR, VLSI program, VM/CMS, Cyber 730, building delays, finances; CSIRONET: 110 nodes, more gateways, microprocessor developments, encryption, software development |

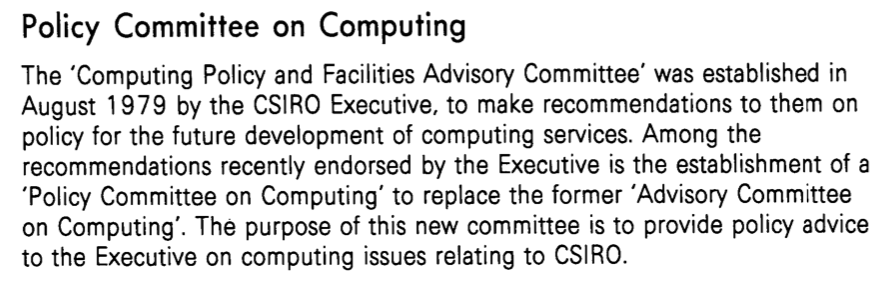

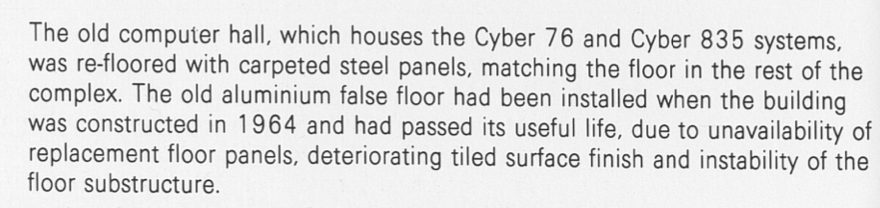

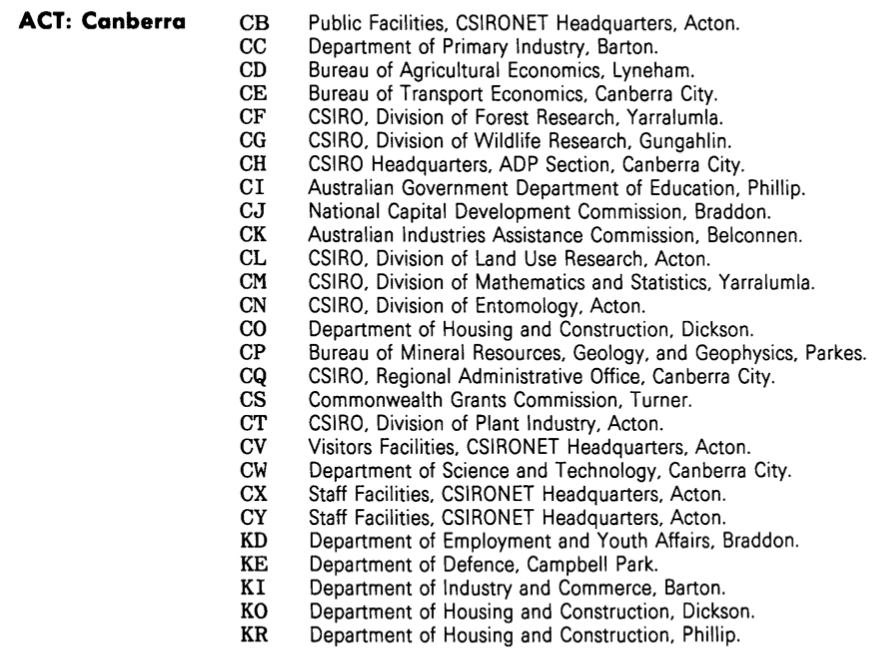

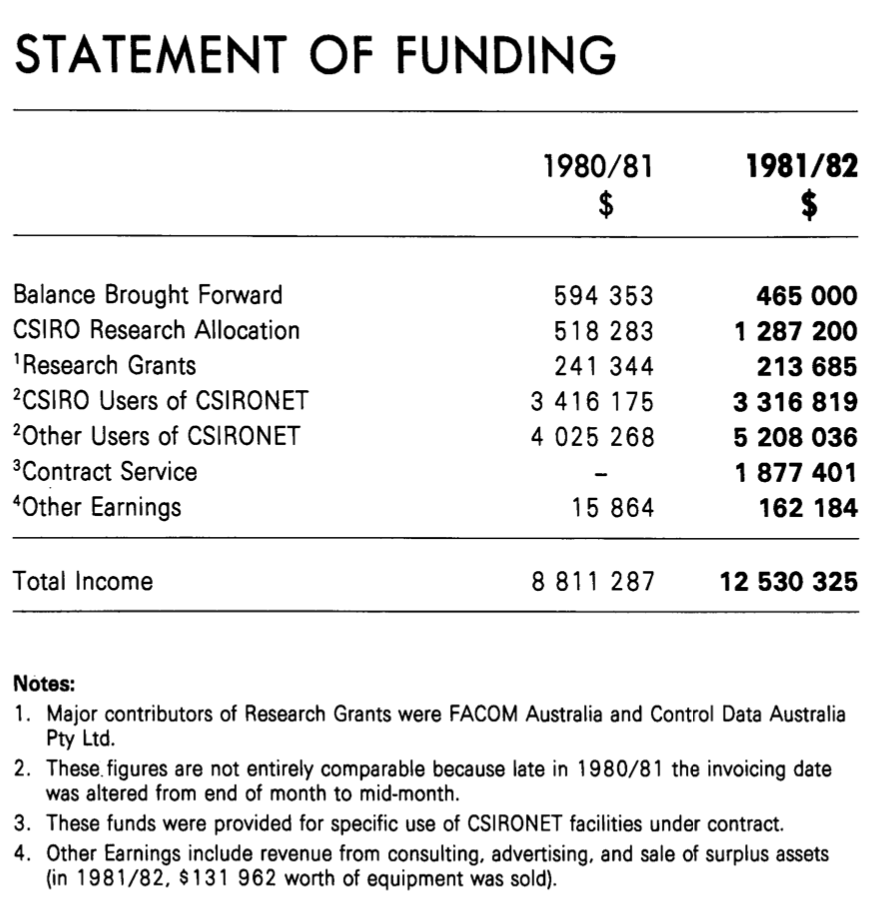

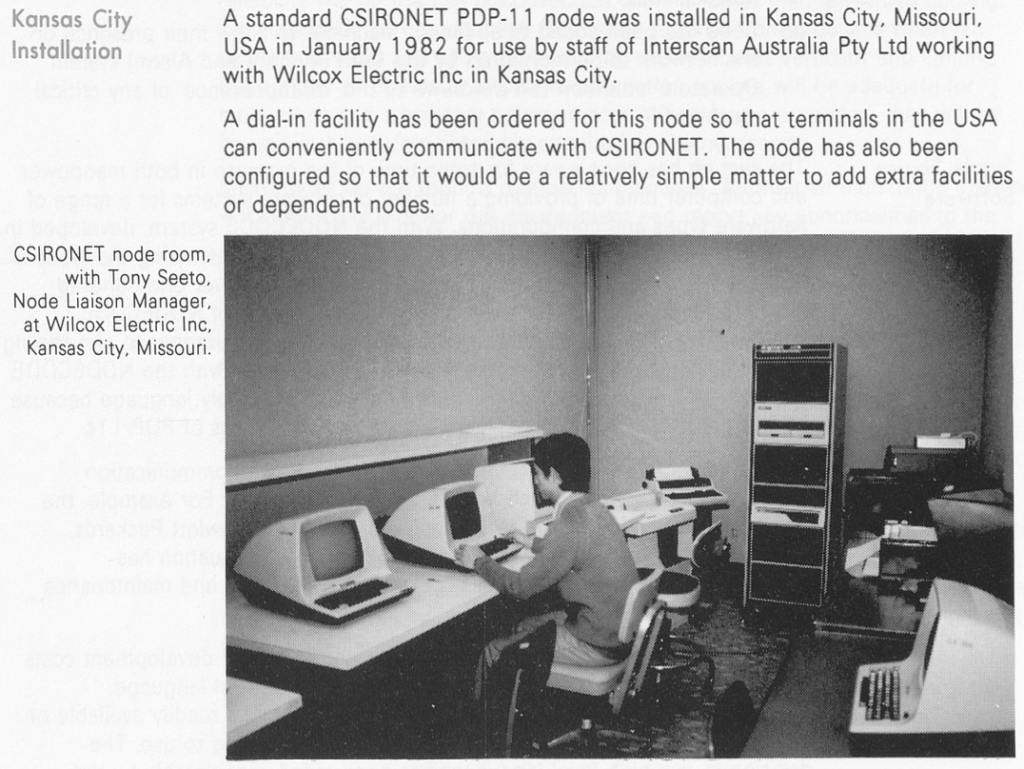

| 1981-82 – DCR, CSIRONET charter, new policy committees, DSS usage, VLSI advancements, new computer hall in use, Cyber 835, VAX 11/730, TFS delayed; CSIRONET – micronode development, 140 nodes, gateways (UNIX), first overseas node; improved software methodologies |

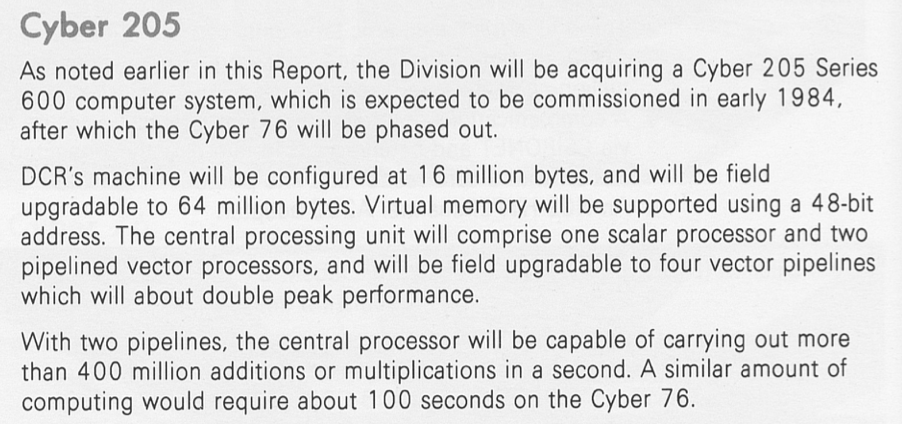

| 1982-83 – DCR, Cyber 205 announced, TFS available, CSIRO Review of DCR; CSIRONET – 141 nodes, micronode deployment, gateways, VAXes |

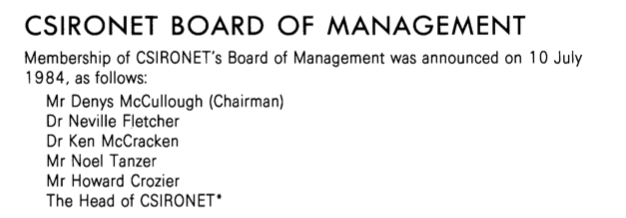

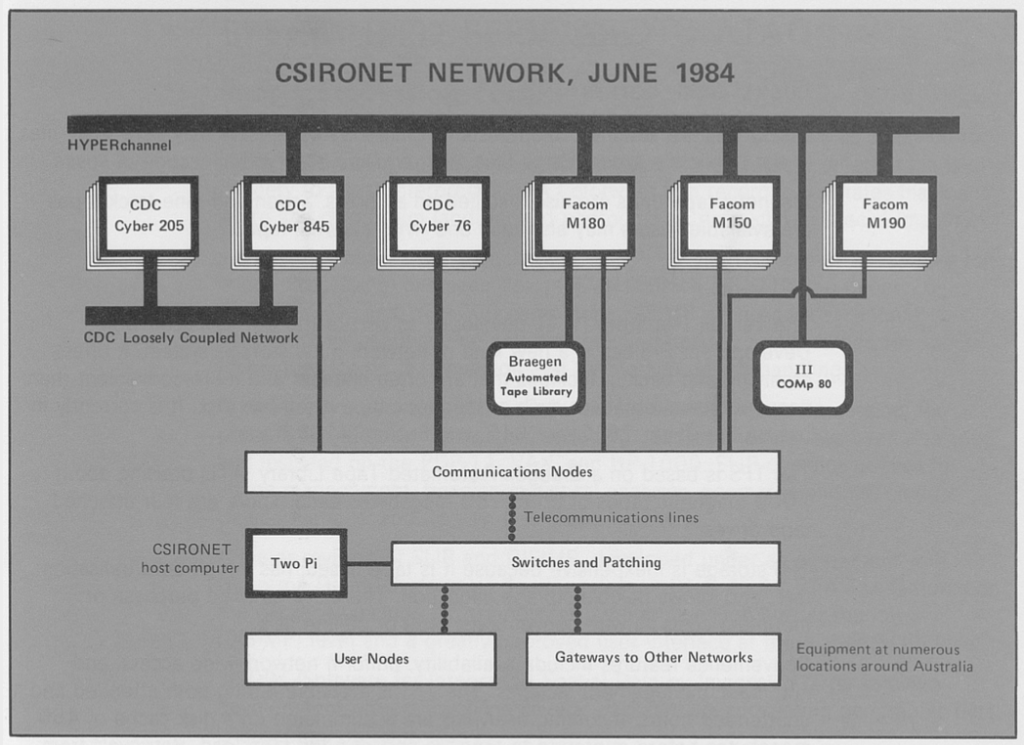

| 1983-84 – DCR – to be split into CSIRONET and DIT; Cyber 205 arrived, TFS available, ; CSIRONET – 100 user nodes, micronode deployment, gateways, UNIX workstation. See also Chapter 3b: R. Bell UK Met Office visit |

| 1984-85 – DCR – The End |

| Summary |

1967 – DCR, DAD, Document Region management, disc

- Division of Computing Research

The newsletter 28 announced on 1 October 1967 that the Computing Research Section would in future be known as the Division of Computing Research – the standard discipline-based unit for CSIRO. But DCR was different – it did do research, but was mainly providing a service. Dr Godfrey Lance was the inaugural Chief.

C.S.I.R.O. Division of Computing Research – Newsletter No. 28 – 1.10.1967

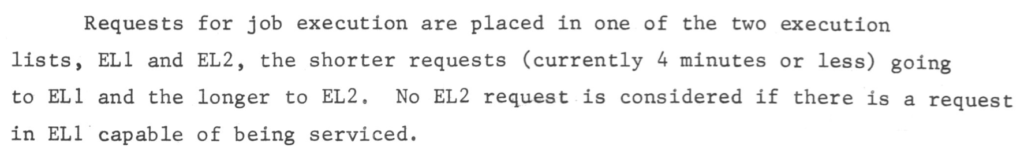

This is quite clever – if short jobs are running, then only more short jobs can run, as would be typical during peak periods: at other times, longer jobs are supported.

Another scheduling issue arose with the partitioning of batch jobs into two classes – short and long. Here’s an appeal to users to help.

Clearly, there were difficulties in managing such a small space in the face of high demand.

Charging was an ongoing process – attempts were made to cover costs:

Charging aimed to encourage acceptable behaviour from users, using both carrots and sticks!

1968 – DCR, widening applications, displays, more branches, evolution of on-line storage and management, first PDP, interactive editing (FRED), teletypes, first remote access, Trevor Pearcey seconded to CDC

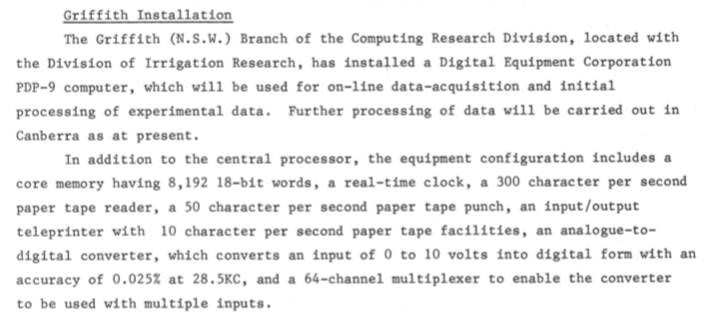

However, DCR was branching out – the first facility outside a capital city was established at Griffith, and access was provided in Brisbane for the first time.

However, DCR was branching out – the first facility outside a capital city was established at Griffith, and access was provided in Brisbane for the first time.

Peter Hanlon added (private communication Jan 2020): “A later development popular in Queensland provided job submission on Telex tape!”

Peter Hanlon added (private communication Jan 2020): “A later development popular in Queensland provided job submission on Telex tape!”“The disc in question (CDC813) consisted of 2 stacks of 18 platters about 600mm in diameter. 64 of the platter surfaces were used for storage totalling 100 million 6-bit characters. Every weekend it was buffed and polished by CDC engineering staff in readiness for the next week. The disc occupied a box about 1800L X 900W X1700H with a separate box of electronics.

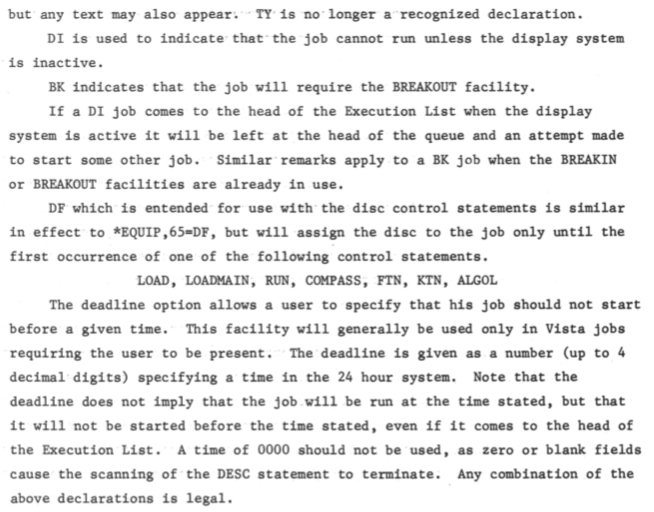

A new control statement was available under DAD on the 3600, supporting the scheduling of jobs. It allowed users to specify that the displays had to be inactive for the job to run (perhaps because it needed all available memory), and other restrictions. For the first time, it allowed job execution to be deferred until after the specified time of day. These facilities allowing restrictions and deadlines are still important in scheduling today – for example, the NCI job parameter “-lstorage=gdata/<project>”.

Jobstacking was the process of copying card decks to tape at the branches, followed by airfreighting tapes to Canberra. The limitations of this were starting to appear, and advice being offered hinted at things to come in source code management.

Jobstacking was the process of copying card decks to tape at the branches, followed by airfreighting tapes to Canberra. The limitations of this were starting to appear, and advice being offered hinted at things to come in source code management.

Notice was given of changes to the plotting routines, used for driving the drum plotters. However, a poor early decision was noted, with the removal of a Fortran Common block called RHHUDSON, the name of a key staff member!

Notice was given of changes to the plotting routines, used for driving the drum plotters. However, a poor early decision was noted, with the removal of a Fortran Common block called RHHUDSON, the name of a key staff member! The newsletter announced the arrival of equipment for the Perth branch – there was no connection to the East coast, but there was a connection by telephone lines to UWA.

The newsletter announced the arrival of equipment for the Perth branch – there was no connection to the East coast, but there was a connection by telephone lines to UWA.

However, each vendor and operating system had its own ‘standard’ until ANSI Standard X 3.27 arrived.

However, each vendor and operating system had its own ‘standard’ until ANSI Standard X 3.27 arrived. Further branches were coming into operation, with Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) PDP series being favoured (after the first installation of a PDP-8 in Canberra).

Further branches were coming into operation, with Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) PDP series being favoured (after the first installation of a PDP-8 in Canberra). Interesting to note how the word ‘man’ would no longer be used in the context of appointments like the one above and the one below!

Interesting to note how the word ‘man’ would no longer be used in the context of appointments like the one above and the one below!

And, funds for major expansion were not available.

And, funds for major expansion were not available. The idea of daily turnaround seems primitive, and yet that is often the case now for users of shared HPC systems that are heavily loaded!

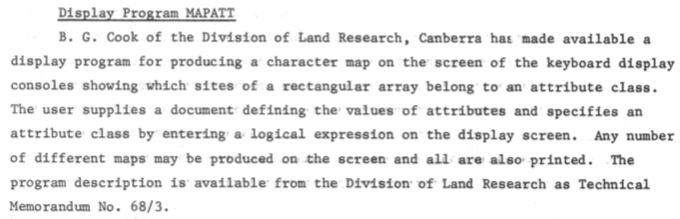

The idea of daily turnaround seems primitive, and yet that is often the case now for users of shared HPC systems that are heavily loaded!Mr A (Tony) Bomford of the Commonwealth Division of National Mapping made very innovative forays into early mapping of the continent.Various groups from the Bureau of Mineral Resources (John Brown, Roy Whitworth) analysed magnetic anomalies from air and sea surveys.The Commonwealth Department of Works (Hans Kardon) used plotter facilities for cut-and-fill depictions of major roadworks.”

Thousands of people will have used FRED and its successors Ted and Ed, including programming using boxes, which could hold text and/or commands.

Thousands of people will have used FRED and its successors Ted and Ed, including programming using boxes, which could hold text and/or commands.

The next was an ‘advanced’ lecture on using magnetic tapes and plotting.

The next was an ‘advanced’ lecture on using magnetic tapes and plotting.

DCR went on to develop the storage services, utilising the three tiers of drum, disc and tape, providing a virtual view of the tiers, and providing one of the first Hierarchical Storage Management (HSM) systems, with automatic recall of off-line files. See the presentation “Pre-history: the origins of HSM in scientific computing in Australia” referenced in the resources section.

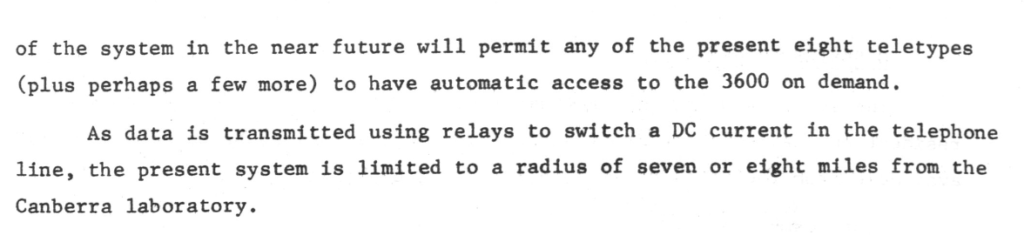

The September 1968 Newsletter No. 38 reported that “Circuitry for the connection of remote Teletypes to the 3600 via the PDP-8 is now complete. A Teletype using this system is now in daily use at the Division of Land Research in Canberra to execute and edit programs, The installation of Teletypes at a greater distance awaits P.M.G. type-approval of the equipment and the availability of lines.”

The Newsletter also contained:

This showed the very limited range of interactive services available at this stage.

The October 1968 Newsletter No. 39 contained an announcement about major improvements to FRED, the document editor, and work by Peter Ewens (who moved to DCR later) to allow Fortran programs to use the displays and teleprinters.

DCR Newsletter No. 40 November 1968 contained much information about the use of magnetic tapes, the primary large-scale storage media at the time. There was a shortage of tapes, a shortage of space to store them, a cautionary note about using unlabelled tapes and an announcement about a UTILITY program to copy tapes and documents. There was an item about changes to the Resident Monitor Length – the memory used by the operating system – which impacted how much memory was left for user programs (in the days before virtual memory). There was a long item about access to random access storage (drums and disc), with compatibility between the 3600 and the 3200s. Dr J.F. O’Callaghan and Mr. E.H. Kinney joined DCR. There was an item about recovery of the 3600 (particularly documents) after a malfunction of the operating system, which used to require a reload of all documents, but now provided better protection. There was an item about PULSAR and TRACER, which provided snapshotting to show the parts of a program that used the most time, and tracing of the call tree.

Two-shift operation was announced for the Melbourne and Sydney facilities, providing 12 hours service initially, and then to be expanded.

DCR Newsletter 41 December 1968 provided the usual list of new publications (including new library functions and subroutines), and then addressed the problems caused by two programs having identical identifiers. On the 3600 where many documents are simultaneously stored on the drum prior to execution, the duplication could lead to crossed files. Two jobs labelled INTENT and INTEGR would both produce output documents called INTE61.

Users in Griffith would now generally receive a 24-hour turnaround for jobs on the 3600. As well, improvements were being made to the PDP-9 there, to allow development for programs to be run on the 3600, to circumvent unnecessary loading of library routines from tape, and to interface an Analogue-to-Digital Converter.

Staff news announced the Dr. B.J. Austin had left for GE (he later returned), and that Mr. R. B. Stanton had joined from UNSW.

The DAD system was enhanced to allow three levels of job priority – VISTA jobs, breaking jobs, and normal jobs.

3600 job listings were enhanced to show the total time charged at several stages of a job.

Back to start of 1968 Back to top

DCR Newsletter 42 February 1969 announced a special lecture on STRING, an interactive calculator – this was before the days of any pocket digital calculator.

A Conference on Picture Language Machines was announced – to be held in February at ANU, with many overseas speakers.

In contrast to the current regime of instant access to data, it was noted that monthly Australian rainfall data had been copied to magnetic tape, with a utility being used to extract data from the tape.

Management of shared space on the disc continued to be an issue, with a clever way of removing old data each weekend (the disc was wiped for maintenance, and only recent files were reloaded). The article stated that “The retention period of disc documents remains undefined, as it depends on total disc activity.” This flexible approach is in contrast to other current regimes, that have fixed retention periods, and are either painted into a corner if there is too much recent data, or remove too much data and waste the storage space that users could well use.

More power was added to the control statements that were used to manage documents on the disc.

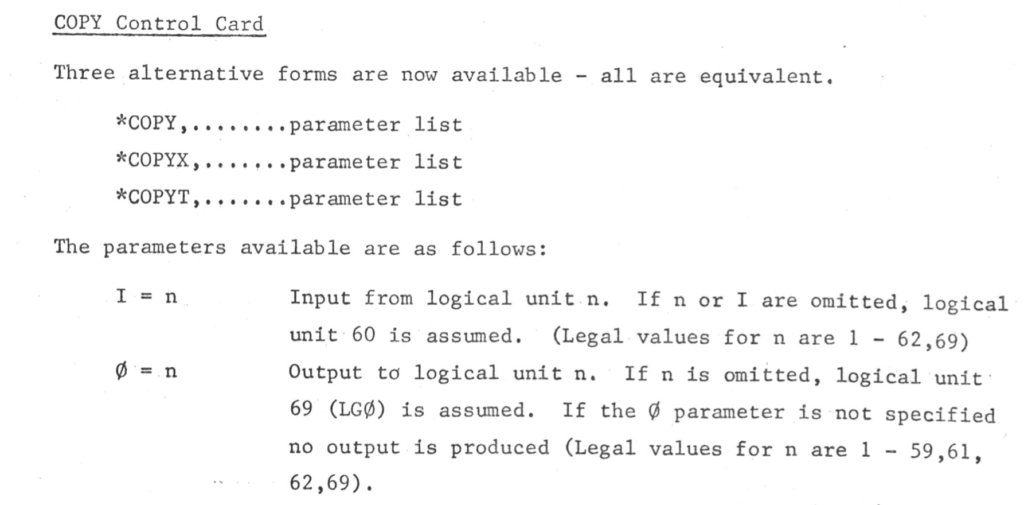

Much of the manipulation of documents (such as copying) was done through a utility called UTILITY – it interpreted selected control statements (for DAD).

Almost all the i/o was done through references to logical units, such as 60 for the card reader, 61 for the printer, etc.

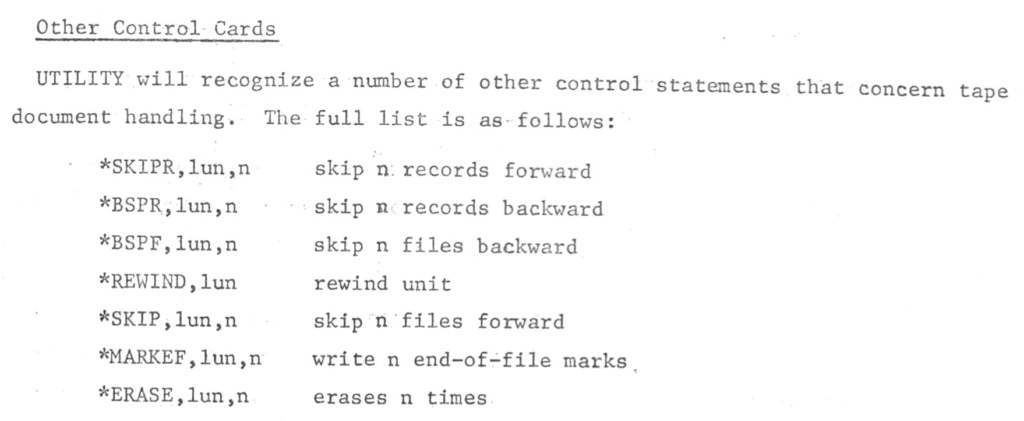

As well, UTILITY would carry out direct operations on magnetic tape: a linear medium, but with the data written in blocks, with multiple records per block possible, and special marks on the tape to signify structure, e.g. to allow multiple files on a tape separated by end-of-file marks.

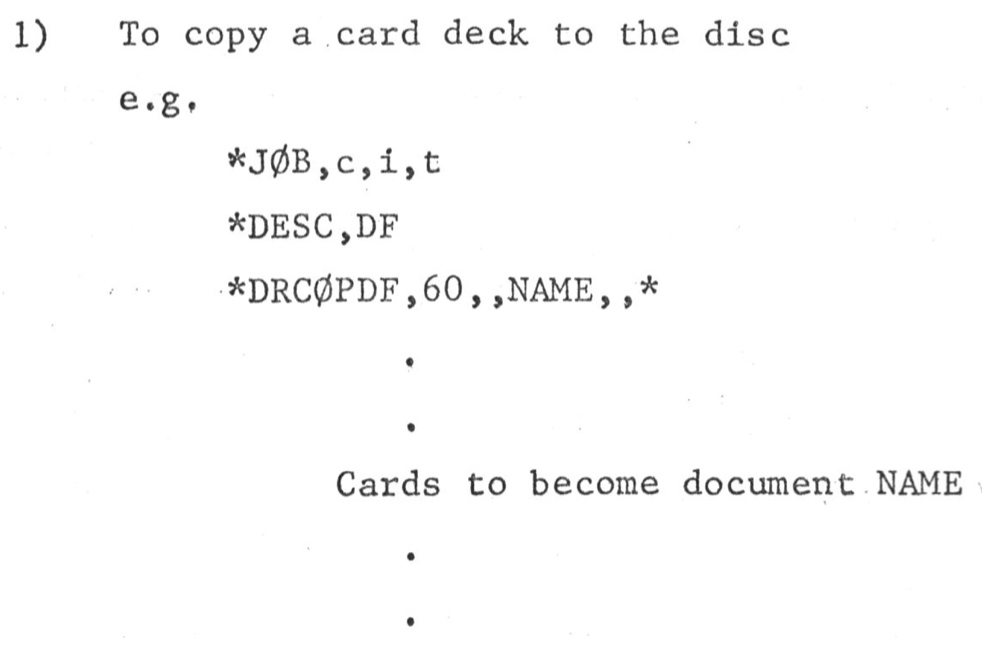

Here is an example job:

If the above seems arcane, try the following for IBM OS/360 families, to copy one file using the IEBGENER utility. (See https://www.ibm.com/support/knowledgecenter/zosbasics/com.ibm.zos.zdatamgmt/zsysprogc_utilities_IEBGENER.htm )

A typical job looks like this:

//SMITH2 JOB 1,GEOFF,MSGCLASS=X // EXEC PGM=IEBGENER //SYSIN DD DUMMY //SYSPRINT DD SYSOUT=X //SYSUT1 DD DISP=SHR,DSN=SMITH.SEQ.DATA //SYSUT2 DD DISP=(NEW,CATLG),DSN=SMITH.COPY.DATA,UNIT=3390, // VOL=SER=WORK02,SPACE=(TRK,3,3))

DCR Newsletter 43 March 1969 provided details of the 3600 job scheduling procedure. The first mechanism provided absolute priority for short jobs over long jobs, but had the drawback of a hard dividing line.

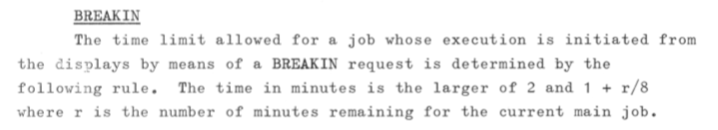

As well, there was a break-in facility for interactive jobs (at this stage available only at the Canberra office). This required a working checkpoint, saving to drum and restart capability – something lacking at most HPC sites for the last decade or so, but vital to be able to provide pre-emption. There was a simple but quite clever formula for deciding whether a breaking job of a requested duration would be run at the expense of a running main job, based on the time to run in the current main job. (But the formula was max(1, 1+r/8) which for positive r is simply 1+r/8).

Here is a table showing the maximum time limit for breakin jobs for various values of r.

| r (minutes) | breakin time limit (minutes) |

|---|---|

| 80 | 11 |

| 64 | 9 |

| 48 | 7 |

| 32 | 5 |

| 16 | 3 |

| 8 | 2 |

| 4 | 1.5 |

| 2 | 1.25 |

| 1 | 1.125 |

The locally developed KWIKTRAN Fortran compiler provided much faster linking and loading, and so enabled better turnaround using the EL1 queue.

(Note the day-shift times – for those not from CSIRO or the Commonwealth Public Service, normal working hours were 36 and 3/4 hours per week, or 7 hours 21 minutes per day, hence the strange ending time. DCR obviously allowed an hour for lunch.)

During this day-shift, shorter jobs gained absolute priority in the short job queue (without regard to how long they had been queued, which was a good idea, but may have been sub-optimal, as some jobs could be stranded by a flood of shorter jobs). And, as still continues, users often requested significantly longer job durations than were needed, either because the duration was hard to estimate, or because they did not want to risk having a job terminate if it hit the time limit.

For the long queue, scheduling was in the hands of the operators, allowing for shorter jobs to run first, or jobs from a particular geographical location, presumably to optimise the return of jobs to the Branches.

Note that the scheduling algorithm ‘is the subject of serious consideration’, a state that continues for many facilities, except perhaps for cloud services, where everything is supposed to run immediately. [We had in the past posited that there would always be the possibility of a change in the workload that would require changes to even the ‘perfect’ scheduling algorithm, to meet goals such as fast turnaround for development, ‘fair’ allocation of resources to organisations, groups and users, and would provide maximum utilisation.]

DCR Newsletter 44 April 1969 highlighted the advantages of KWIKTRAN. One of the new features was the ability to invoke array bounds checking – stepping outside the bounds of an array was one of the most common errors in early Fortran systems.

The physical form of logical data structures were much more evident in earlier systems, as is indicated by this update to a program to block multiple records into blocks on magnetic tape.

DCR Newsletter 45 May 1969 contained and item about magnetic tapes: the start of the continuing reduction in the price of storage. These tapes could hold only about 15 Mbyte, so off-line storage was about $1 per Mbyte. (Modern tape cartridges can hold 20 Tbyte uncompressed, but cost hundreds of dollars, so about $1 per 500 Gbyte.)

I guess a gaudy advertisement might have gone better on TV than on radio, but TV was only black and white then.

The CSIRO Chief Librarian was looking to the future of information processing, not just the ‘computing’ capabilities of the systems.

John O’Callaghan went on the become Chief of the Division of Information Technology, and also the Director of the ACSYS CRC and APAC.

The Chief was about to go overseas for about two months – no acting Chief was named.

A new interactive program was released which had the new feature of allowing the disc to be used by multiple users, rather than being locked to one user for an entire session! The earlier version seems primitive, but locking and queuing would have to have been built in to the new version – not trivial.

DCR Newsletter 46 June 1969 contained an article on a conference on computers in secondary schools – far-sighted.

There was a growing movement of using the capabilities of computers for their communications facilities.

The 4th ACC was announced, highlighting ‘leading men in their field’. This was in an era when women in the public sector had to leave employment upon marriage.

DAD continued to be developed and published.

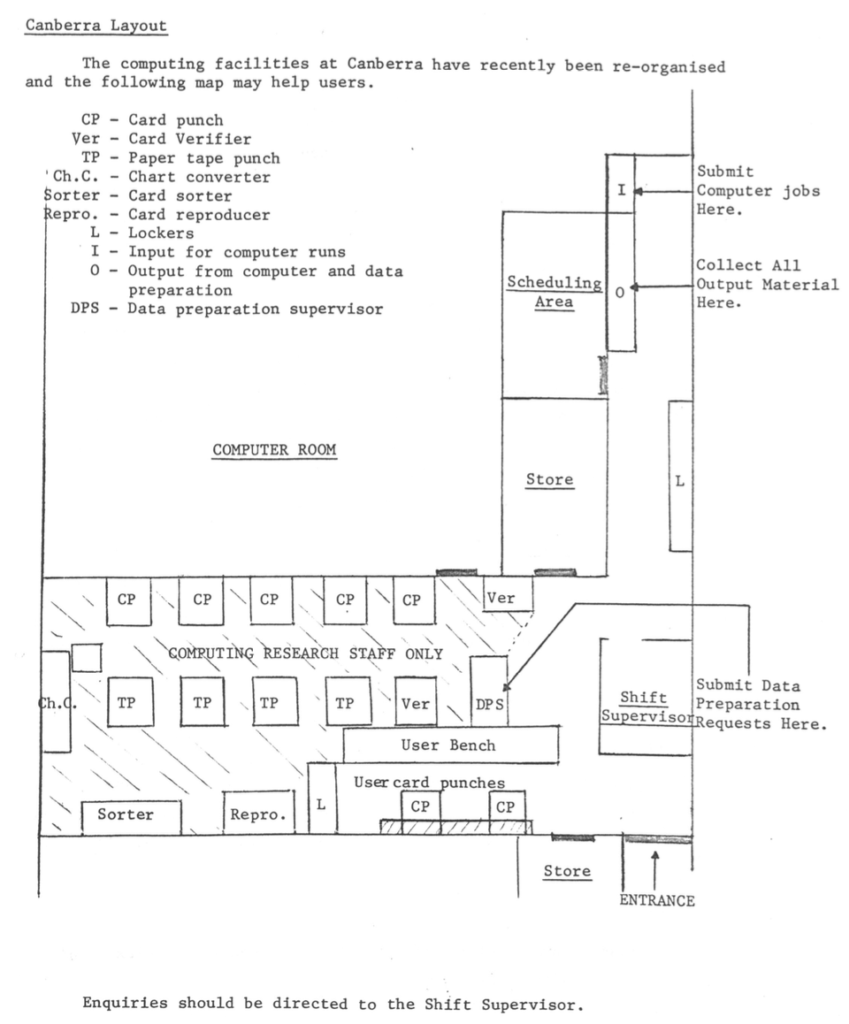

The production of cards and paper tape for computer input continued to dominate the facilities, as shown in the diagram below.

Charlie Wallington was appointed acting Chief.

Peter Ewens joined DCR, and had a long career with the systems group.

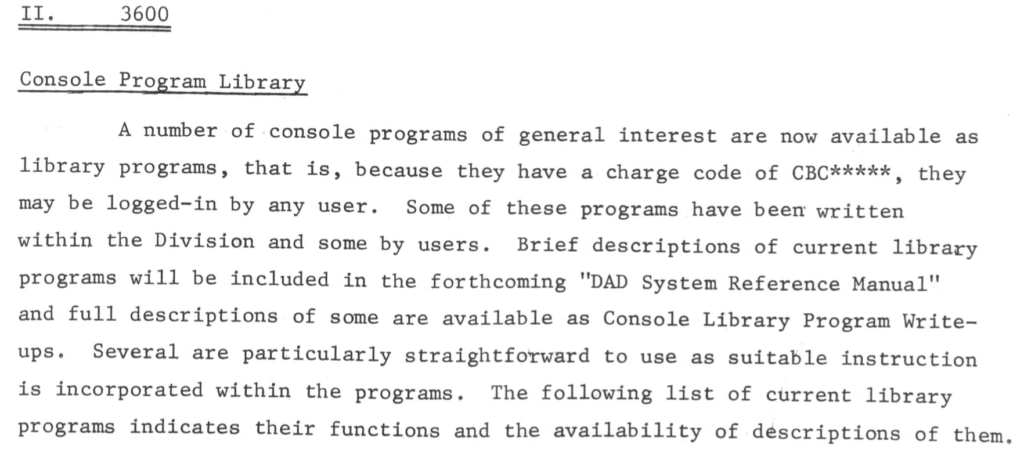

The interactive facilities continued to expand, with many being set up to be used by any user. A list of console programs follows below. Operator support, interactive editing and calculation, document management and games were featured.

A new version of the CSIRO operating system for the 3200s was announced. This was clearly a major effort. Details of improvements were given under the headings of Fortran (12 items), Compass and COSY [the assembler and source-code maintenance system] (7 items), Disc Software (11 items) and Additional Features [including improvements to the automatic assignment of labelled tapes, and a number of bugs being removed from Algol] (7 items).

1968-69 – DCR, displays, appeal for expansion, Perth branch

This became a recurring theme over the years: lack of finance for expansion to meet the needs.

This became a recurring theme over the years: lack of finance for expansion to meet the needs.Back to start of 1968-69 Back to top

DCR Newsletter 47 July 1969 was short, and contained the following item.

I’d imagine this change was needed to stop a precipitous flush when the drum was under pressure.

DCR Newsletter 48 Aug 1969 contained the following. This one highlighted an advantage of the new disc facilities on the 3200s.

Small computers were being deployed for data collection.

Trevor Pearcey continued to write about the potential of computers for non-numerical applications.

DCR Newsletter 49 Sep 1969 contained an article by Chris Billington about a cross-assembler and loader for HP minicomputers running on a CDC 3200. This illustrates the growing use of ‘small’ computers, and the relative lack of software on such systems compared with the ‘mainframe’ CDC 3200.

The newsletter also announced the departure of Charlie Wallington for UNSW, the appointment of Jan Lee (who went on to a long career at DCR and Csironet), and the overseas visit of John Russell to study large computer centres.

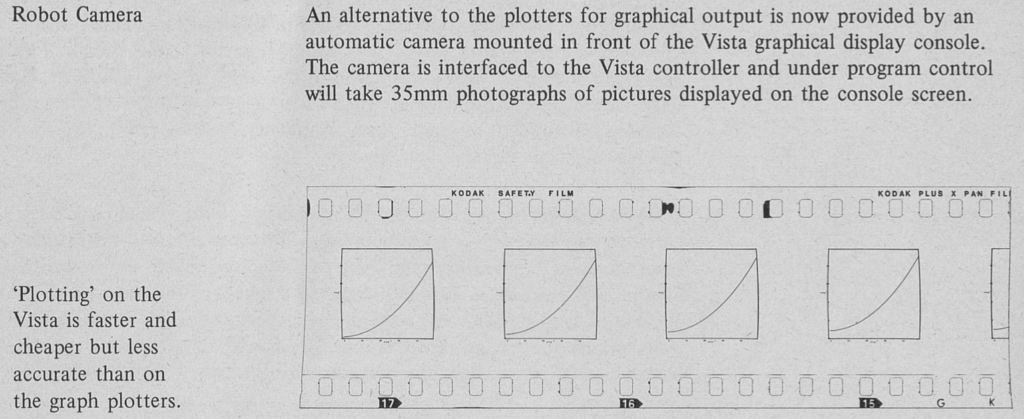

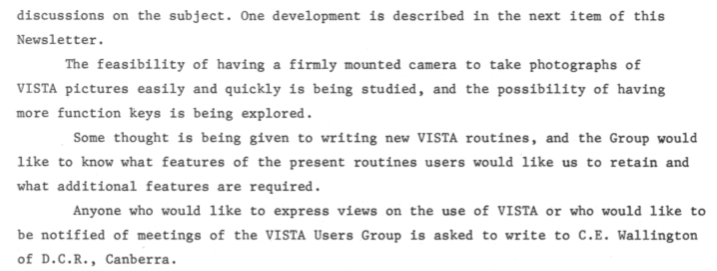

DCR Newsletter 50 Oct 1969 contained an article about a new camera which would have enabled near publication standard pictures to be acquired from the Vista screens.

Here is the first announcement of working remote access – the start of the network. The hold-up was the availability of lines, so the network could have started in October 1968.

Storage space was at a premium, but changes to squeeze the size of plot files required a large charge increase to cover costs.

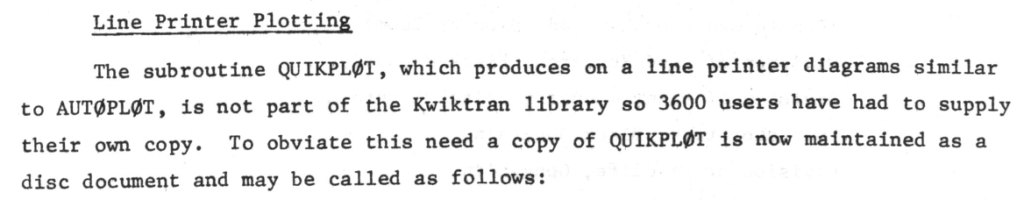

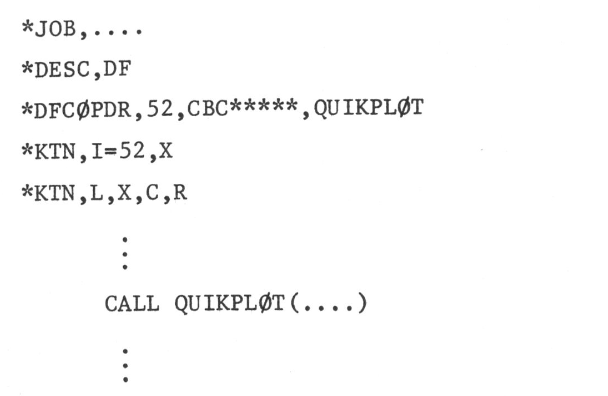

And, here was another way to produce graphical printed information – line printer plots.

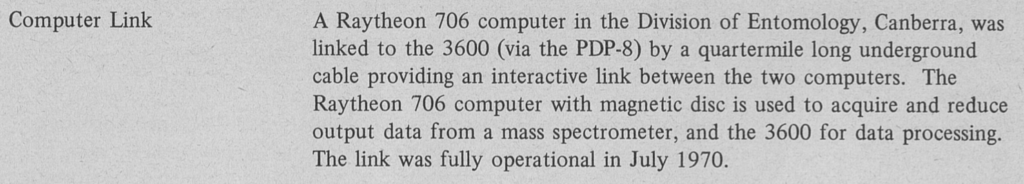

1969-70 – DCR, wide-area network=CSIRONET, access to CDC 6600, multi-user disc access, interactive job scheduling, computer-to-computer link, visualisation

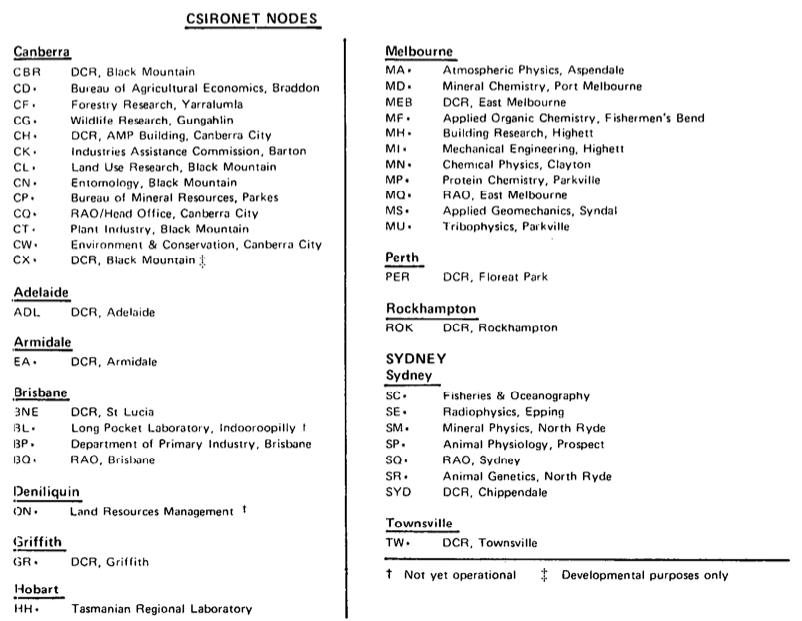

CSIRONET

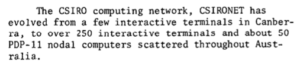

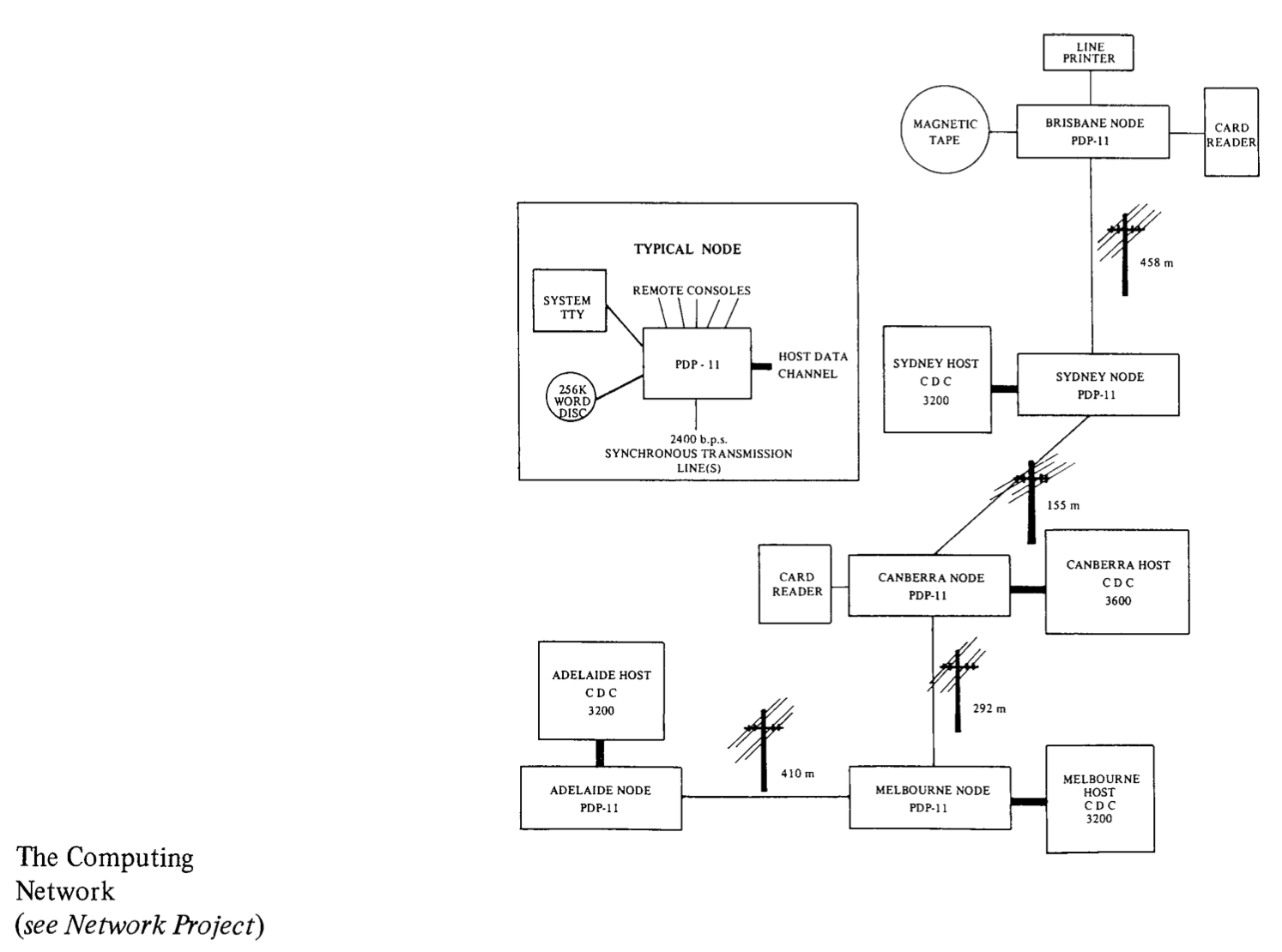

DCR developed a packet-switched network from about 1969, the year the DARPANET was started (which became the Internet). Over time, users could have remote card-readers, printers, plotters, and paper-tape readers and punches, and teletypes or visual terminals attached to a local node (PDP-11). Ten characters per second was the standard speed for teletype terminals, with 30 characters per second for display terminals being considered fast. Most CSIRO sites acquired the basic node, card reader and printer, and often had a DCR staff member as operator by the mid-1970s. For example, Kay Challis at Aspendale.

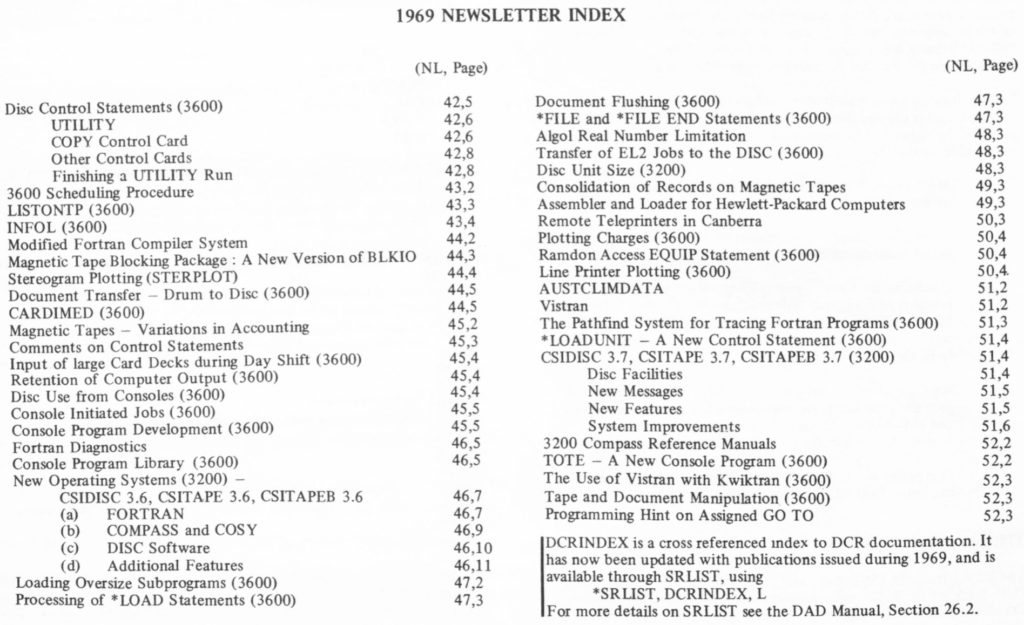

From this point, I’ll mostly leave out items from the Newsletters, and concentrate on the Annual reports. However, from Newsletter 53, January 1970, here is the index to the 1969 Newsletters.

Back to start of 1969-70 Back to top

1970

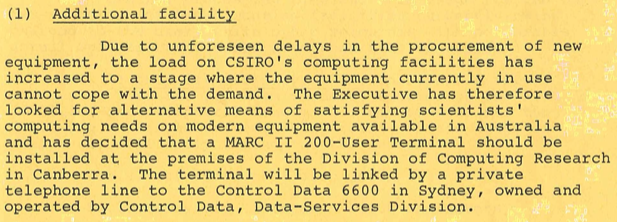

The beginning of 1970 brought an announcement in a CSIRO information circular of access to a CDC 6600 installed in Sydney.  The information circular also announced charges being applied to not just computing time and drum storage, but to disc and tape storage, tape mounting and the mounting of non-standard paper on output peripherals.

The information circular also announced charges being applied to not just computing time and drum storage, but to disc and tape storage, tape mounting and the mounting of non-standard paper on output peripherals.

The 6600 had a peak speed of 3 Mflop/s, compared with 0.35 Mflop/s for the 3600. (Seymour Cray aimed for each successive system he designed to have an order of magnitude higher performance than its predecessor – part of this was achieved by advances in the hardware, but also by advances in the architecture. The 3600 was essentially a serial machine (though i/o was offloaded somewhat), the 6600 had multiple functional units allowing simultaneous CPU operations, and the 7600 had pipelined multiple functional units, allowing an assembly-line operation, and had a peak speed of 36 Mflop/s.)

Furthermore, the disc access was revised to allow simultaneous access by multiple programs – something we barely think about today.

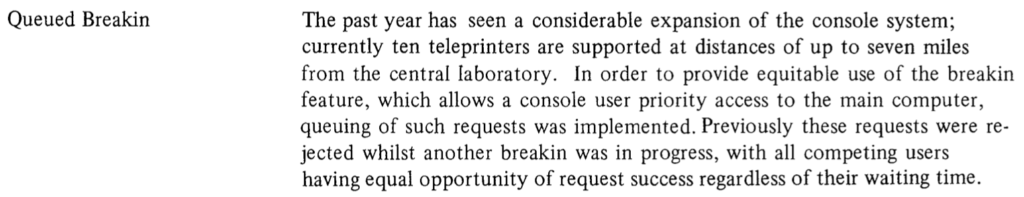

Furthermore, the disc access was revised to allow simultaneous access by multiple programs – something we barely think about today. Another advance was the provision of a queuing facility for exclusive interactive usage – the previous system would have been frustrating.

Another advance was the provision of a queuing facility for exclusive interactive usage – the previous system would have been frustrating. Visualisation recording was enhanced by an automatic camera attached to a display.

Visualisation recording was enhanced by an automatic camera attached to a display.Back to start of 1969-70 Back to top

1970-71 – DCR, two-bank DAD, growth in on-line storage demands – management, Townsville office, job submission via telex, start of network project, interstate lines, PDP-11s, text processing, small computers, DAD exported

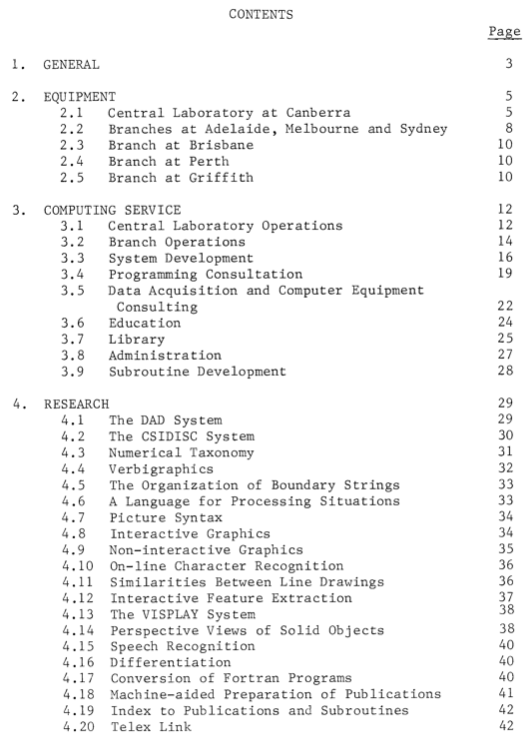

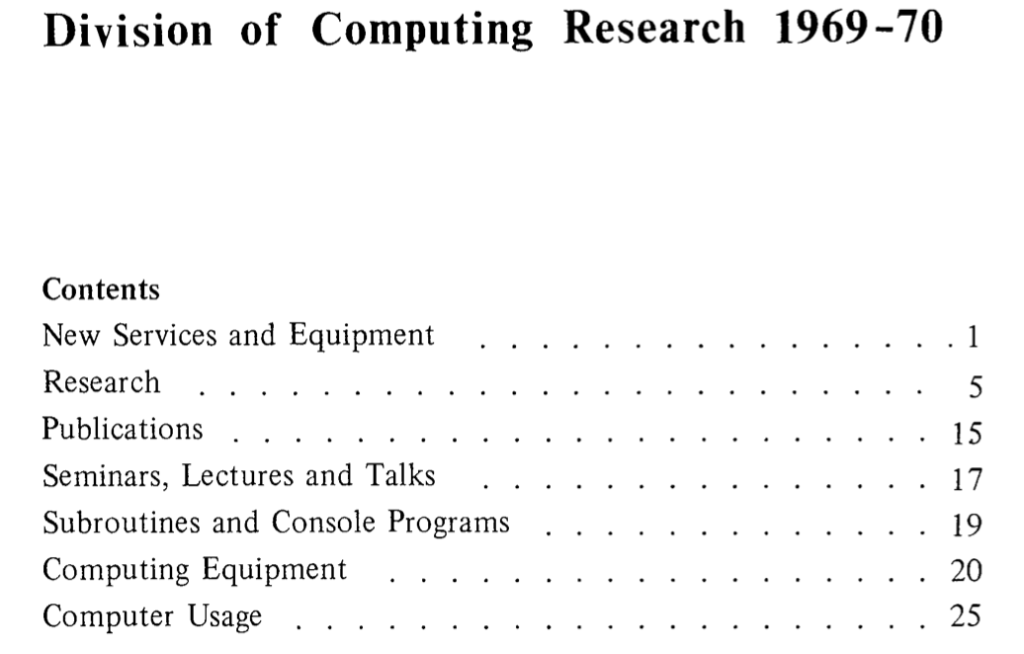

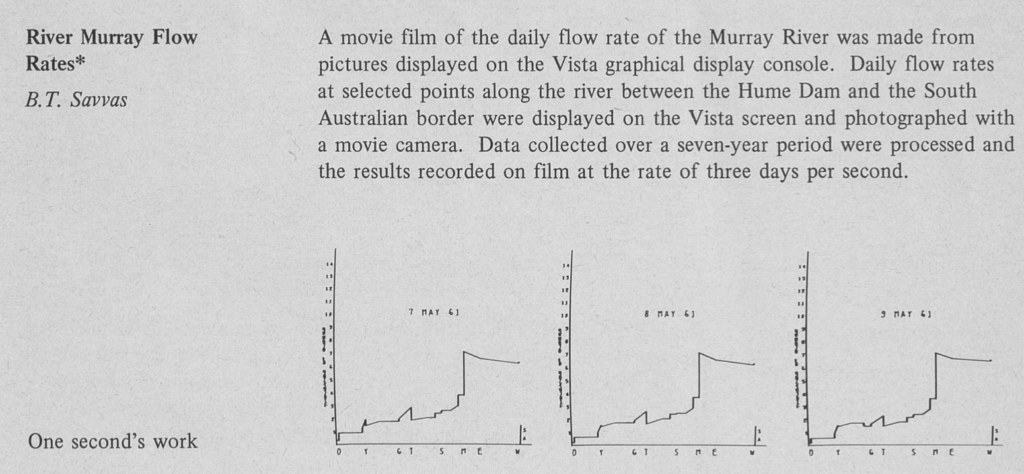

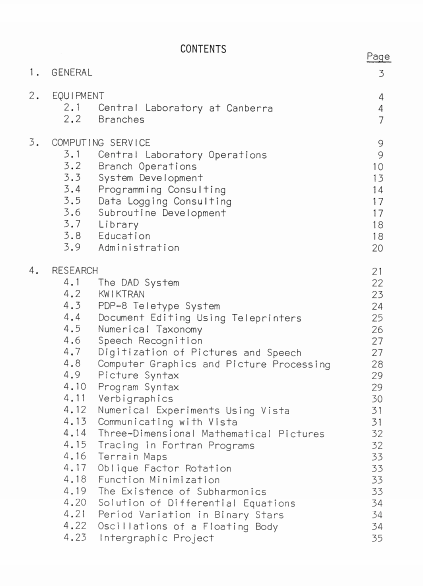

The 1970-1971 Annual Report can be found here. Here are the contents:

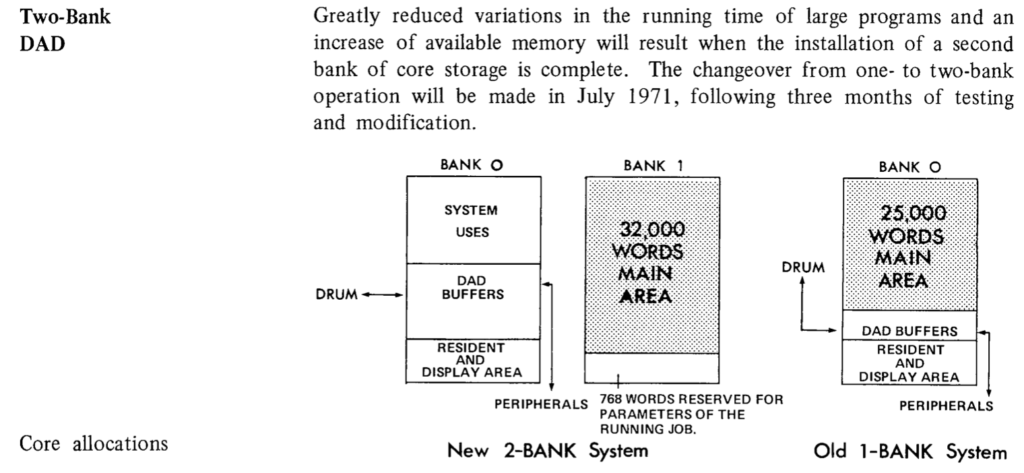

The first item under the “New Services, Software and Equipment” heading was:

It is noteworthy how much of the additional memory was dedicated to system needs, rather than to user programs. By this stage the CDC 6600 (probably with 64 k of 60-bit word memory, or 492 kbyte) was probably catering for jobs requiring larger memory than the 3600’s 1-bank memory of 197 kbyte.

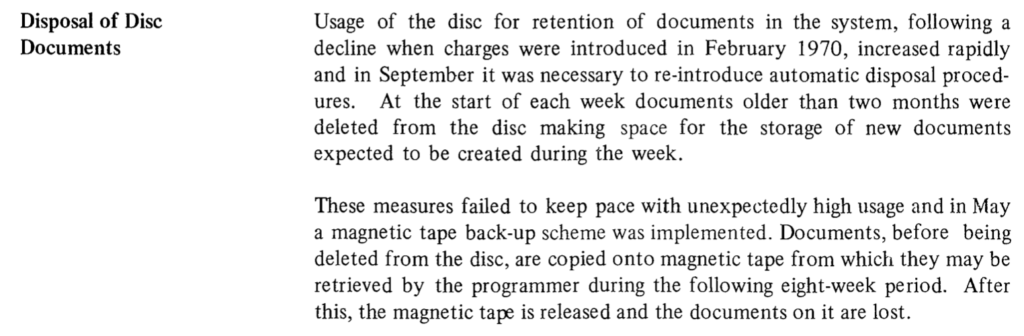

Once users were able to retain documents on on-line storage, the management of this became a problem, illustrated by changing strategies to deal with it. It is gratifying to note how the service continued to grow in supporting users, by providing off-line storage for the overflow.

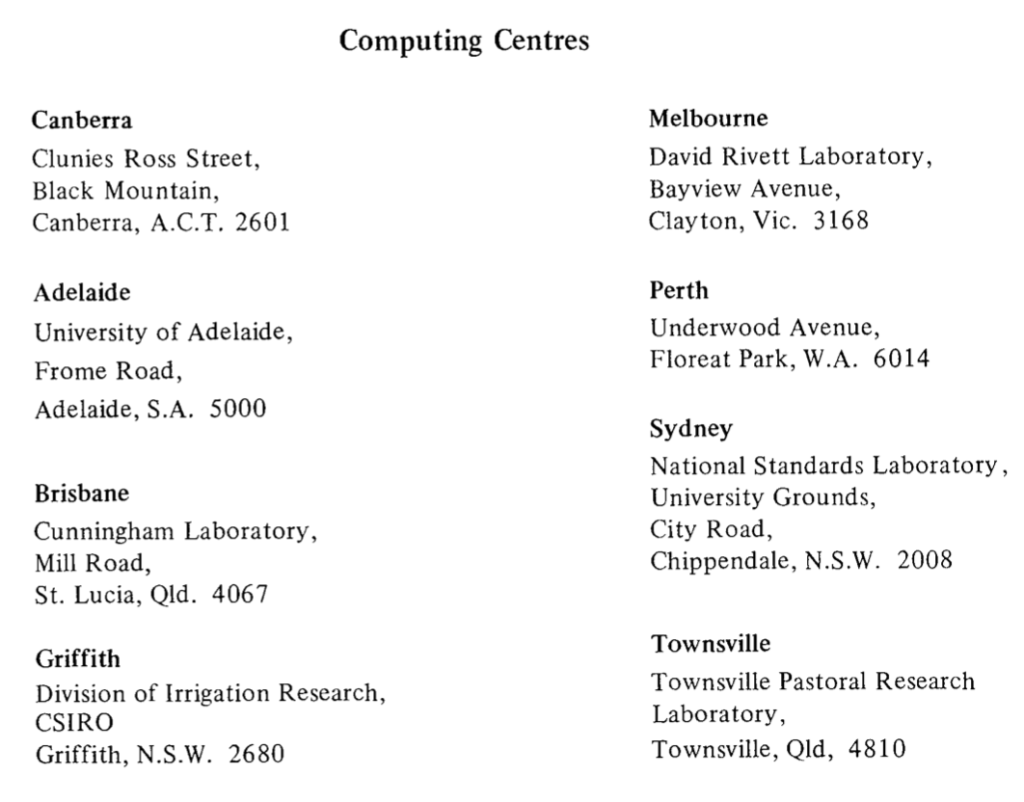

A new office was opened in Townsville during the year, bringing the total to eight.

Publications were moving to digital source, rather than paper, allowing for easier updates to individual pages on paper copies in loose-leaf binders.

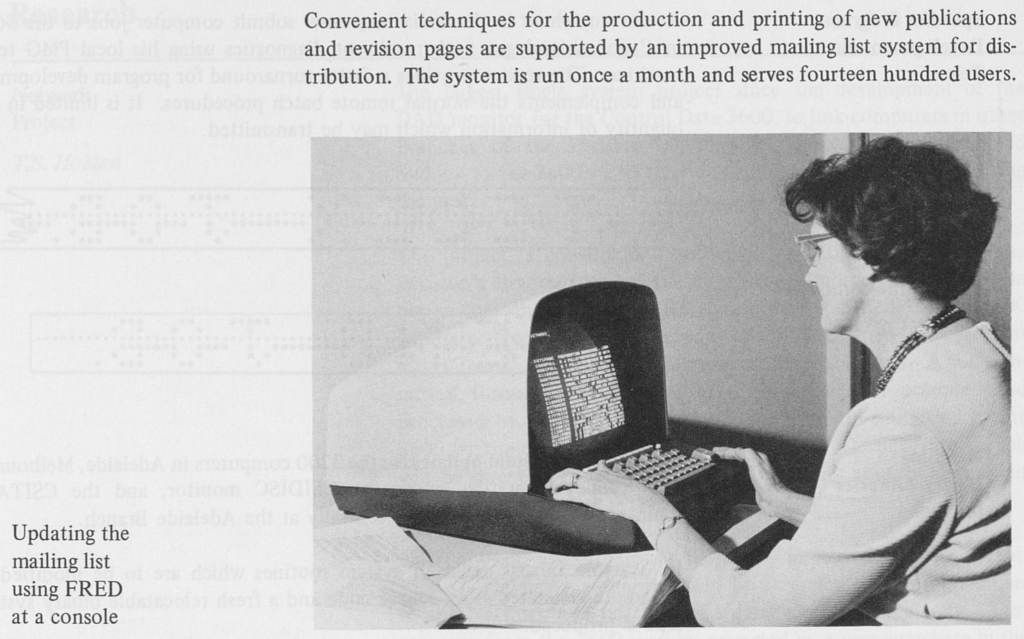

The mailing list was computerised, with the staff member using the on-line text editor FRED.

Townsville was like Perth, in having a PDP-8 to provide access to a nearby university’s PDP-10.

Who would think now that people would use a service to submit jobs using paper tape and a machine on the telex network, which was primarily used for business communications!

The following item gives an insight into the difficulties of maintaining software for remote un-connected machines.

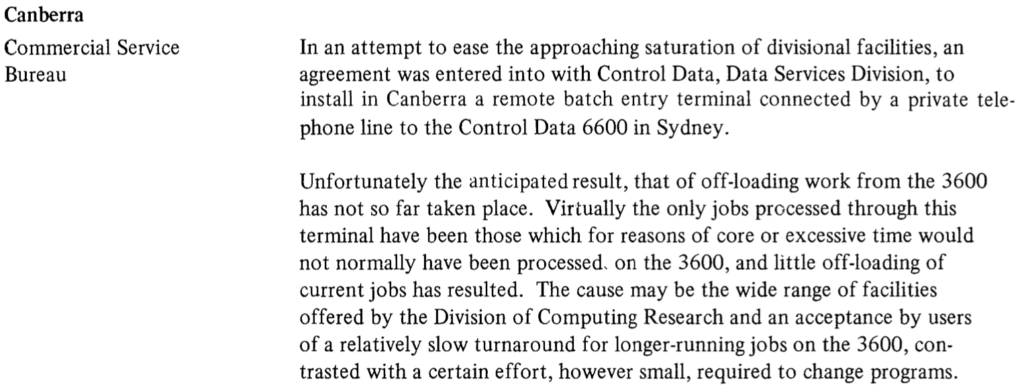

The big item for the year was the commencement of the network project, based on earlier work involving the PDP-8 front-end to the 3600. This planned to allow remote job entry and output to the 3600 in Canberra from the branches, and allow remote interactive access for the first time.

CSIRO was one of the first organisations to make use of the interstate telephone network for data traffic – a speed of 2400 bit/s to each node was planned.

CSIRO was one of the first organisations to make use of the interstate telephone network for data traffic – a speed of 2400 bit/s to each node was planned.

The next item showed the pioneering emphasis on speech processing

– Hello CSIRO perhaps, rather than Hello Siri or Alexa or Google.

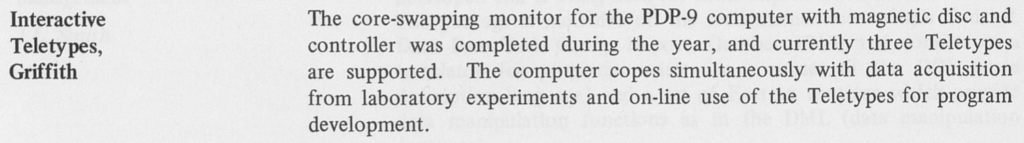

CSIRO wrote its own monitor (operating system) for the PDP-9 at Griffith, to allow time-sharing.

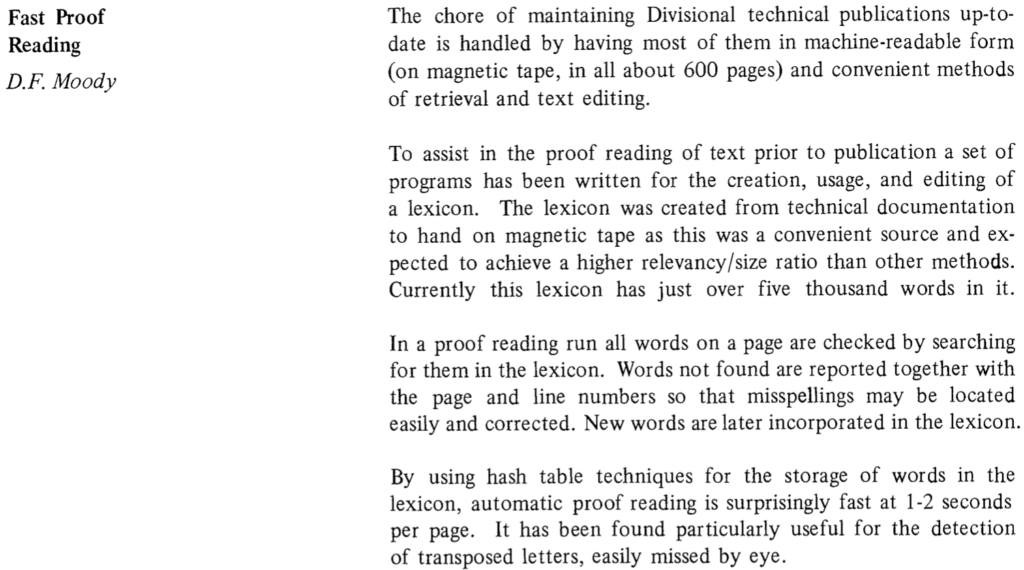

DCR built its own spell checker for its documentation – it built a lexicon from existing technical text, and used that to check any new or revised documentation. Hash-table techniques were used, even at this early stage, to allow proof-reading to execute in 1 – 2 seconds per page.

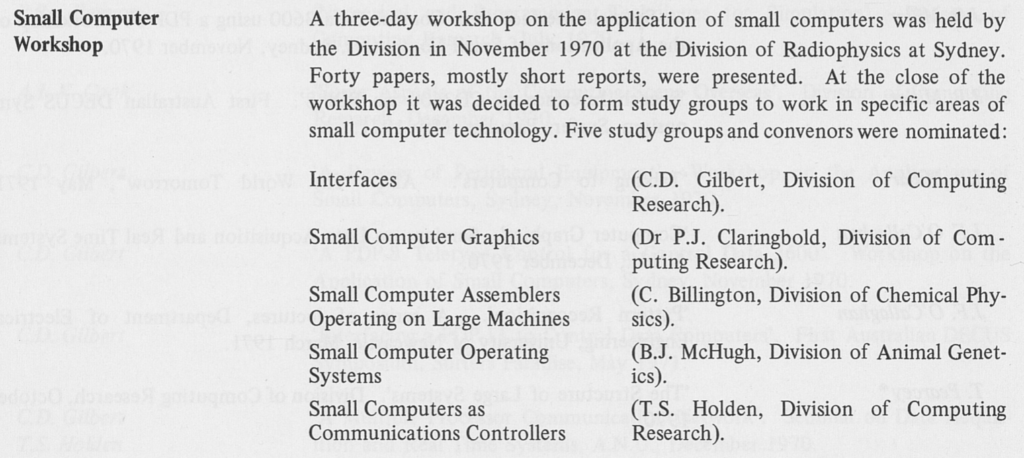

DCR was facilitating the use of small computers in CSIRO Divisions, and hosted a 3-day workshop in November 1970. This led to study groups to work in specific areas. Doubtless, some of the work found its way into the future CSIRONET network facilities, and some led to heavy usage in Divisions of local computers for data acquisition, etc.

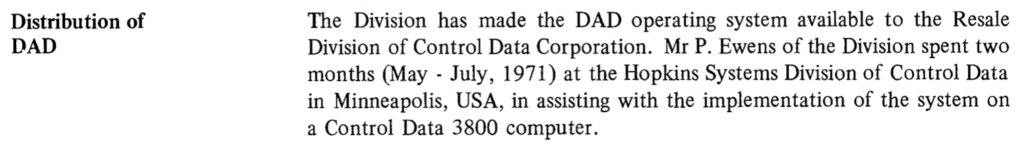

As well as the porting of DAD to the system at Computer Center Santa Barbara as reported in chapter 2, DAD was made available to CDC, and was implemented on a CDC 3800 in the USA with the assistance of Peter Ewens.

Back to start of 1970-71 Back to top

1971-72 – DCR, CSIRONET in operation, PDP-11 nodes at branches, Rockhampton branch, virtual Document Region, reentrant FRED, improved reliability, Claringbold acting chief

The 1971-1972 Annual Report can be found here. The contents page is similar to previous years, and there were no new branches (but see below): The network came into operation under the name CSIRONET:

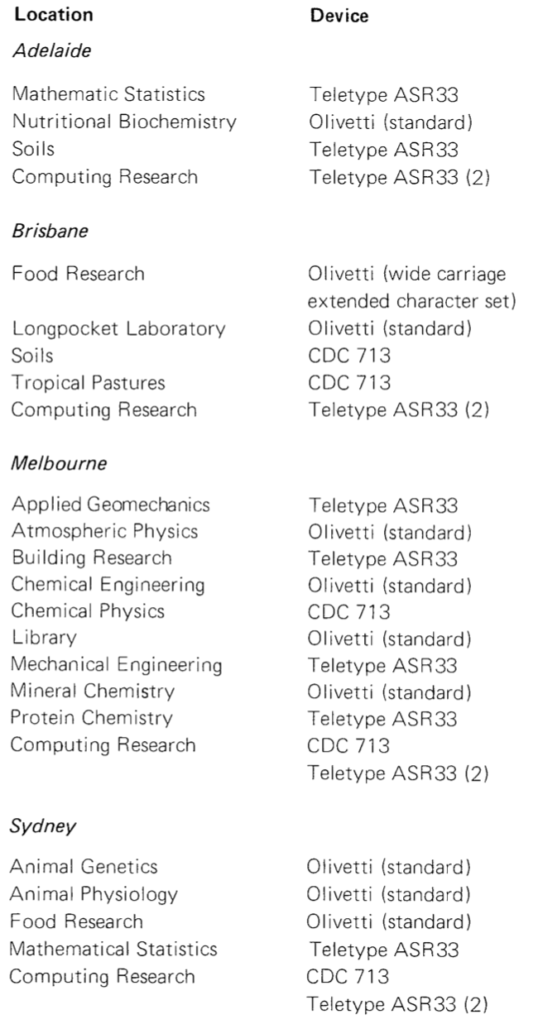

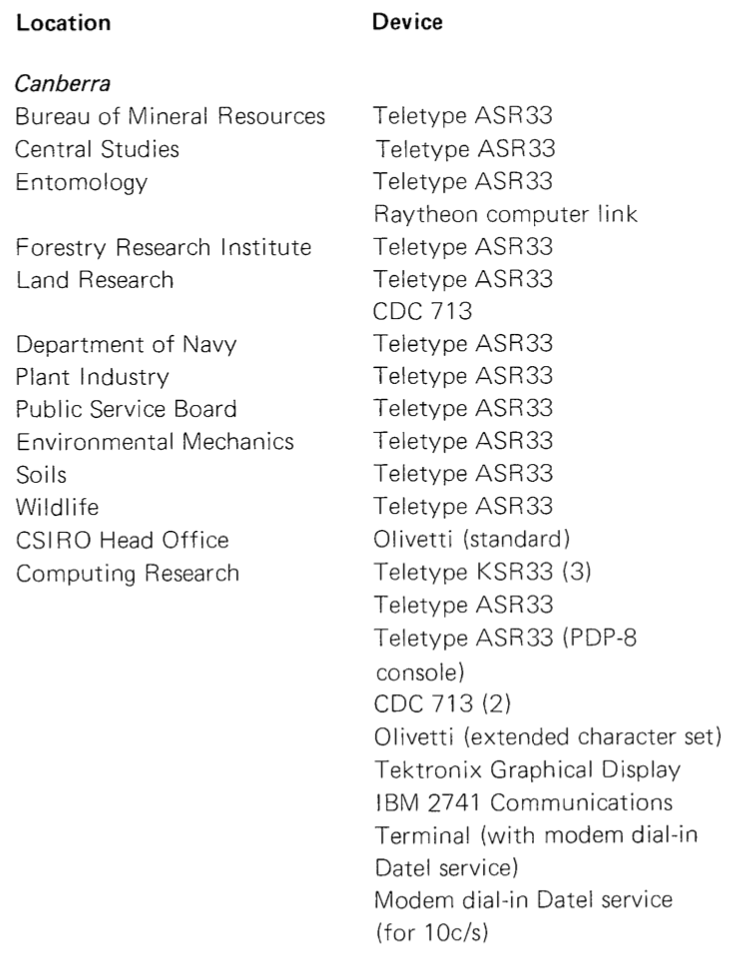

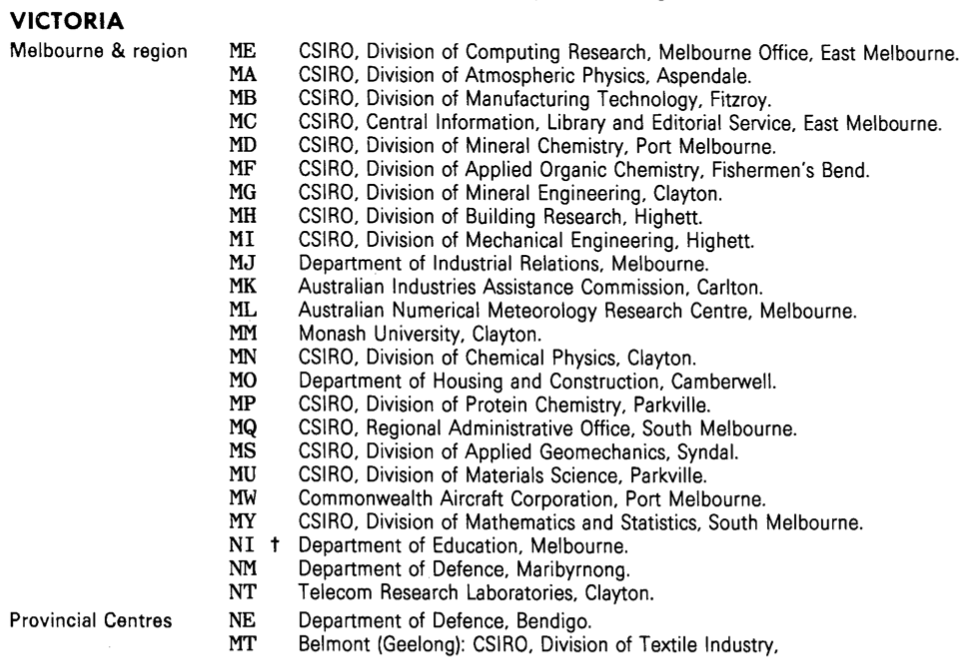

The network came into operation under the name CSIRONET:  Here is the list of consoles: most major CSIRO sites had access, along with several Government Departments.

Here is the list of consoles: most major CSIRO sites had access, along with several Government Departments.

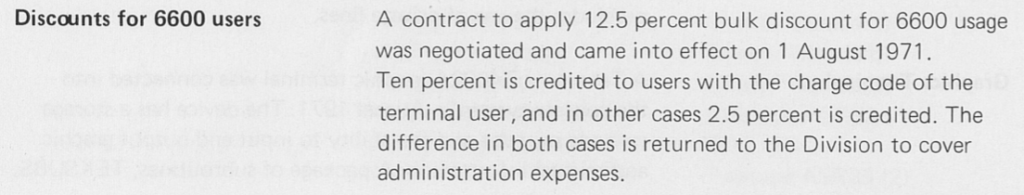

Charging for access to the CDC 6600 was revised downwards, but would, I guess, still be a disincentive to usage.

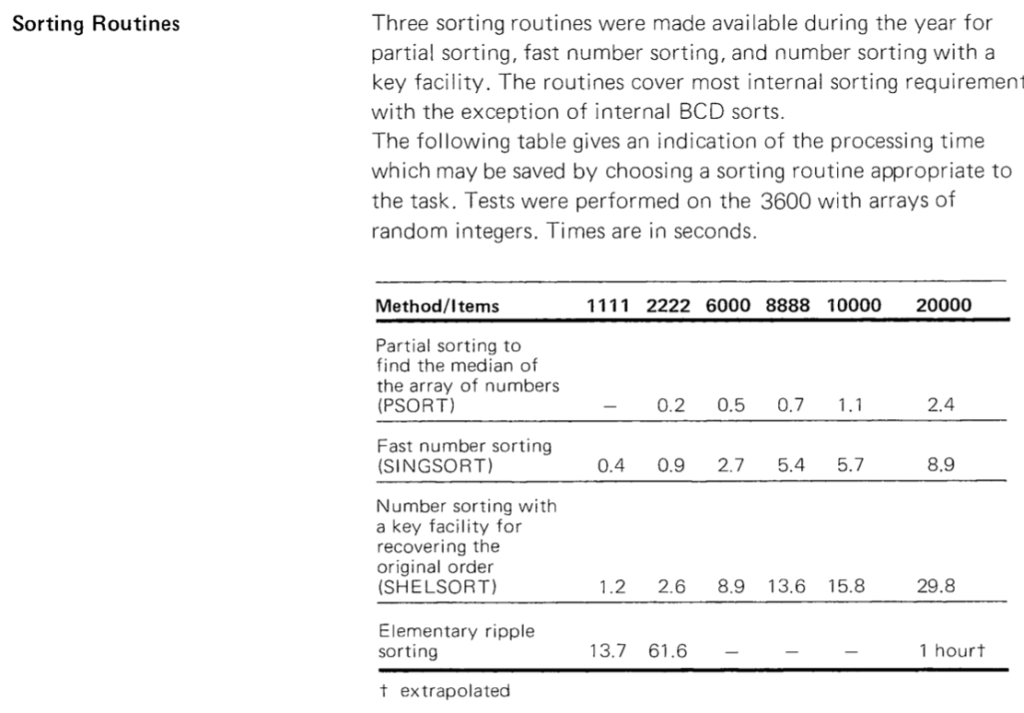

Sorting is one of the fundamental algorithms for computing: DCR provided improved routines with vast improvements over naive algorithms.

Despite the listing of branches under the contents, there was a new branch started in Rockhampton.

The major branches acquired PDP-11s to act as nodes. The start of service date of April 1971 seems at odds with the CoResedarch announcement of service commencement in April 1972.

CSIRO wrote its own monitor (operating system) for the PDP-8/I in Perth, to allow time-sharing.

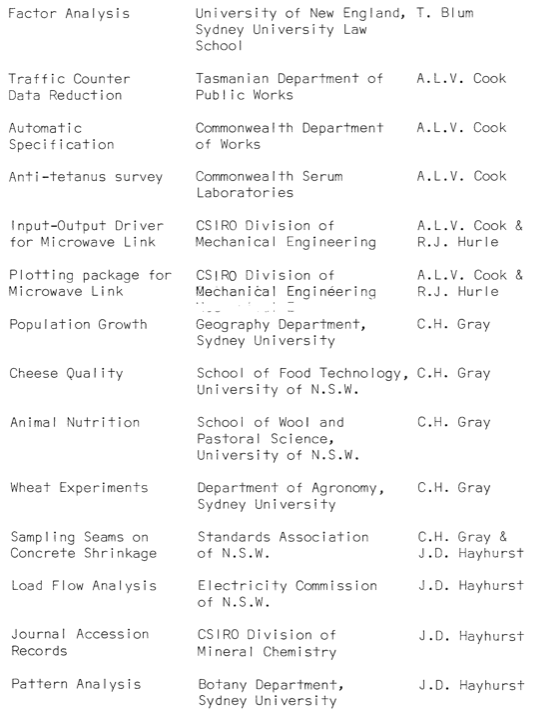

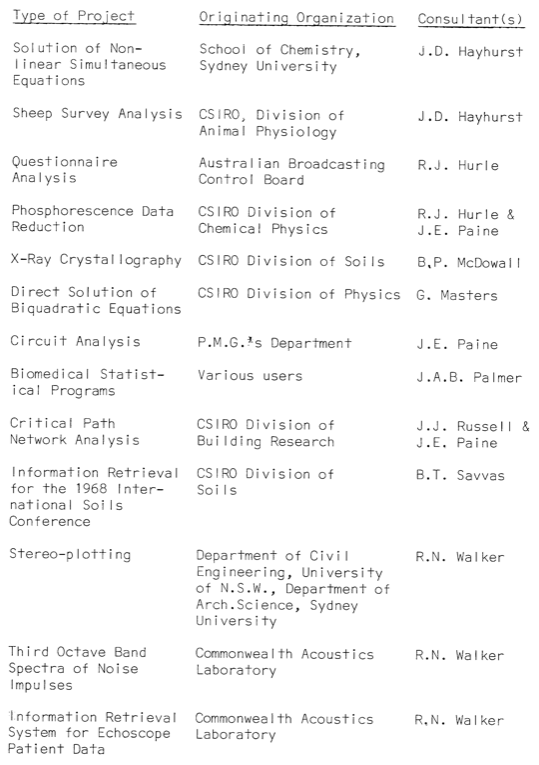

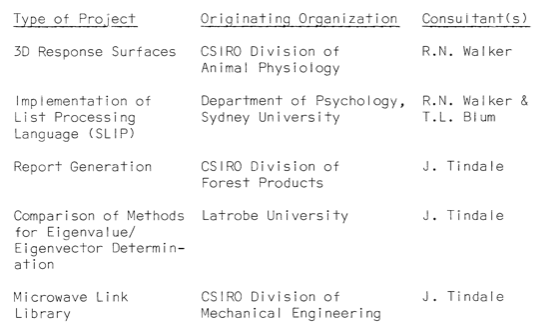

The summary of fields of research gives some idea of the breadth of the applications of computers at the time.

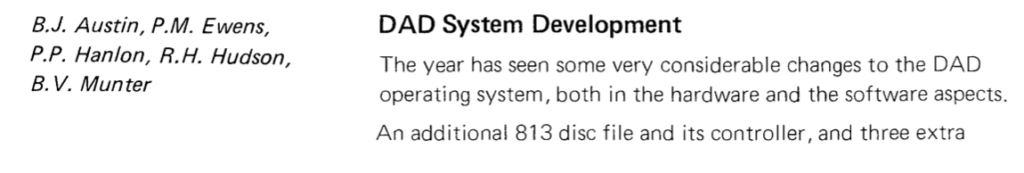

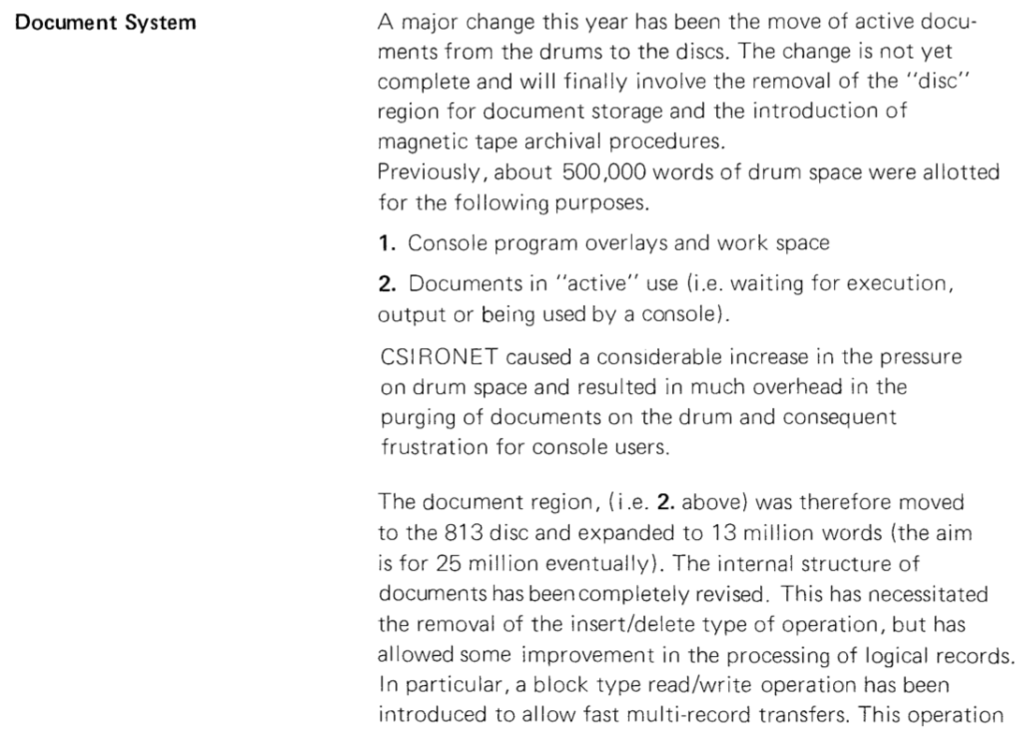

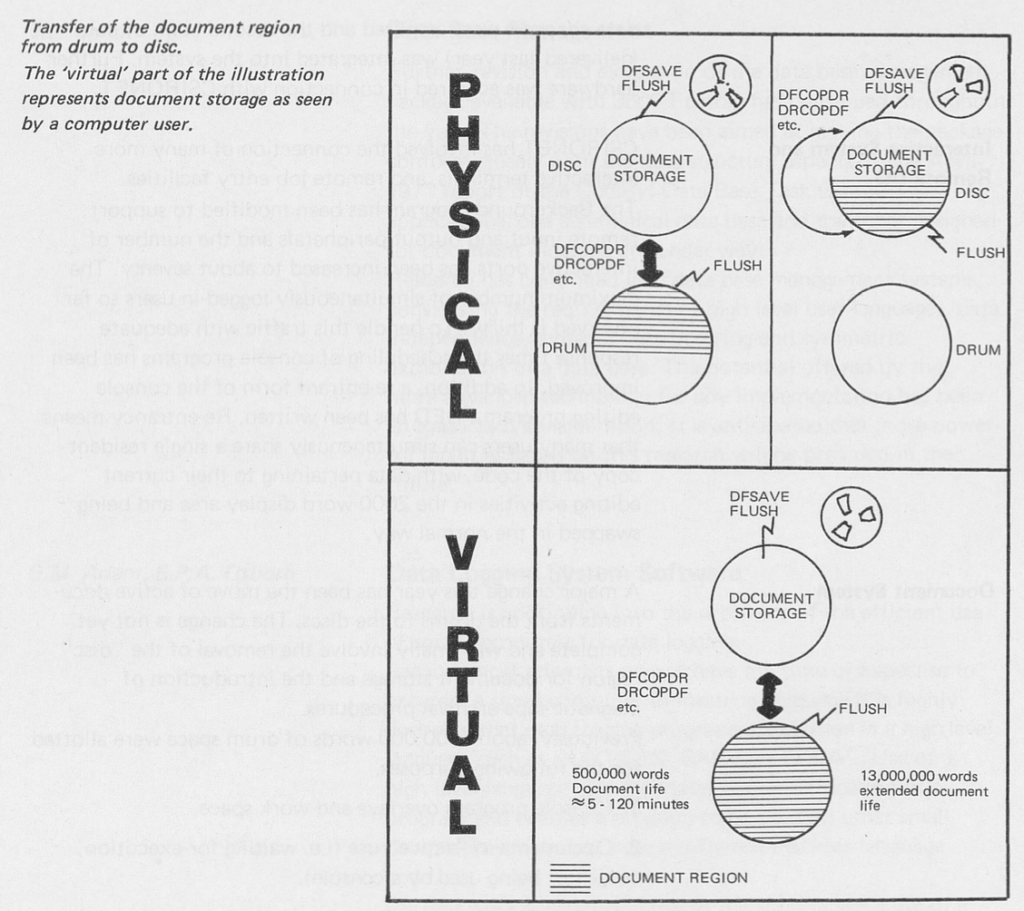

The summary of fields of research gives some idea of the breadth of the applications of computers at the time. Development of DAD continued: additional disc and channels, support for up to 70 interactive ports, improved scheduling, reentrant code, and the virtualisation of the Document Region spanning drums and disc, with overflow to magnetic tape,; and system reliability (to support interactive use).

Development of DAD continued: additional disc and channels, support for up to 70 interactive ports, improved scheduling, reentrant code, and the virtualisation of the Document Region spanning drums and disc, with overflow to magnetic tape,; and system reliability (to support interactive use).

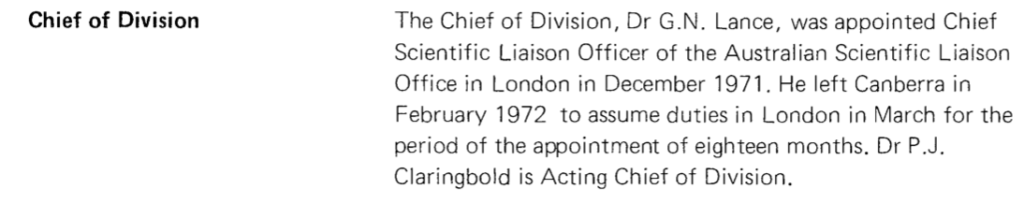

Finally, the Chief, Dr Godfrey Lance took up a position in London, and Dr Peter Claringbold became Acting Chief – a sign of things to come later in the 1970s.

CoResearch 157 April 1972 announced the start of operations of SIRONET (later CSIRONET, then Csironet).

Interactive access was supported by a CSIRO-developed text editor called FRED (then TED and later ED). Henry Hudson was the main developer. Versions for the Cyber 76 (Ed, using the additional LCM) and FRED for PDP-11s were developed).

Back to start of 1971-72 Back to top

1972-73 – DCR, Cyber 76 announced and arrives, Margaret Thatcher visits, DR retention periods and becomes and HSM, extension of CSIRONET to provide local nodes, TED replaces FRED – boxes

CoResearch 162 September 1972 reported on a visit by a UK Minister who became more famous.

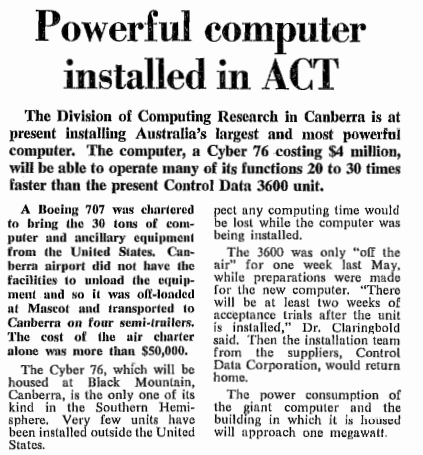

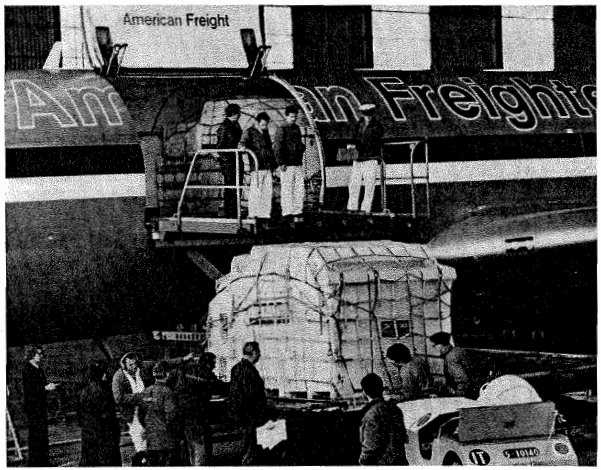

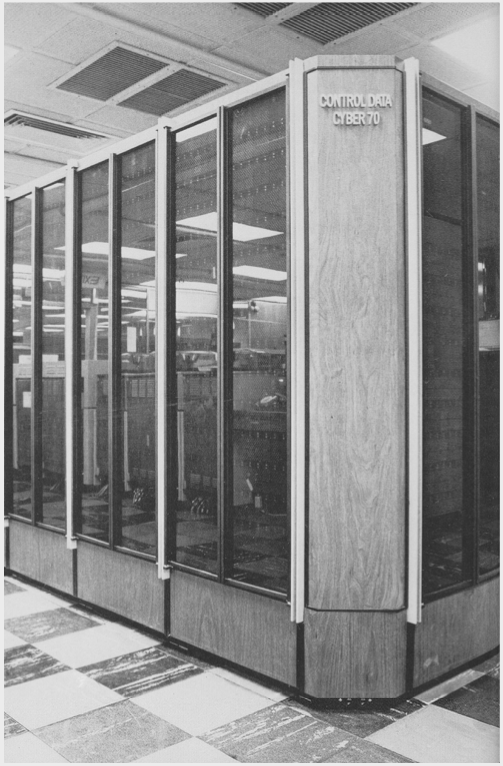

The big news from 1972-1973 was the announcement and arrival of a new CDC Cyber 70 model 76 (Cyber 76).

(Two 7600s. 3D rendering with a figure as scale: from reference CDC 7600)

(Two 7600s. 3D rendering with a figure as scale: from reference CDC 7600)

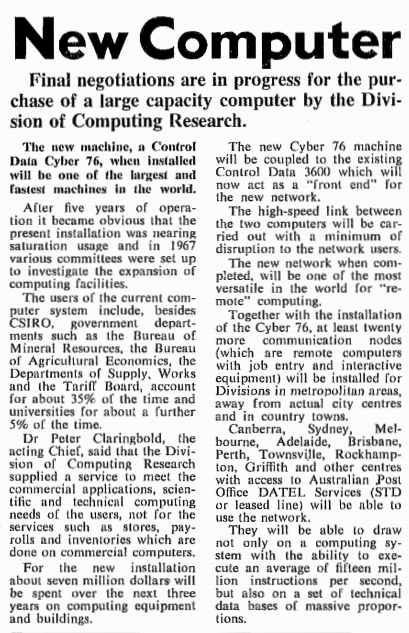

CoResearch 163 October 1972 announced a “New Computer”:

CSIRO acquired the best supercomputer of its time in 1973. The Cyber 76 was a re-branding of Seymour Cray’s 7600, itself a breakthrough machine with multiple parallel pipe-lined functional units, and a follow-on from the CDC 6600. The Cyber 76 had a clock rate of 27.5 ns, had 64 k of 60-bit words main memory (SCM – small-core-memory), and 256 k of 60-bit large-core memory. This was later extended to 512 k words, to support interactive usage, and could comfortably support 100 users across the country doing editing, etc. Its peak speed was 36 Mflop/s. See the reference CDC 7600.

CSIRO acquired the best supercomputer of its time in 1973. The Cyber 76 was a re-branding of Seymour Cray’s 7600, itself a breakthrough machine with multiple parallel pipe-lined functional units, and a follow-on from the CDC 6600. The Cyber 76 had a clock rate of 27.5 ns, had 64 k of 60-bit words main memory (SCM – small-core-memory), and 256 k of 60-bit large-core memory. This was later extended to 512 k words, to support interactive usage, and could comfortably support 100 users across the country doing editing, etc. Its peak speed was 36 Mflop/s. See the reference CDC 7600.

CSIRO acquired the system with Federal Government money, and was required to continue to give access to other government departments. The system was used for nearly every computing task in CSIRO – payroll, libraries and all.

If was rumoured that the CDC salesman received the cheque for the purchase (~$5M) and caused a stir when he banked it into his account at an ordinary suburban bank branch in Canberra. The next day, he had to forward most of the money to the company.

CoResearch 170, July 1973, highlighted the arrival.

The September 1973 Newsletter noted that:

Cyber 76 installation started 9 June

Acceptance tests started 29 June

Acceptance tests completed 13 July

CSIRONET/Cyber magnetic tape link operational 18 July

CY link operational 13 August (DAD system – SCOPE 2.0 system)

CO link operational 22 August (SCOPE 2.0 system – DAD system).

(SCOPE 2.0 was the operating system on the Cyber 76).

Also noted:

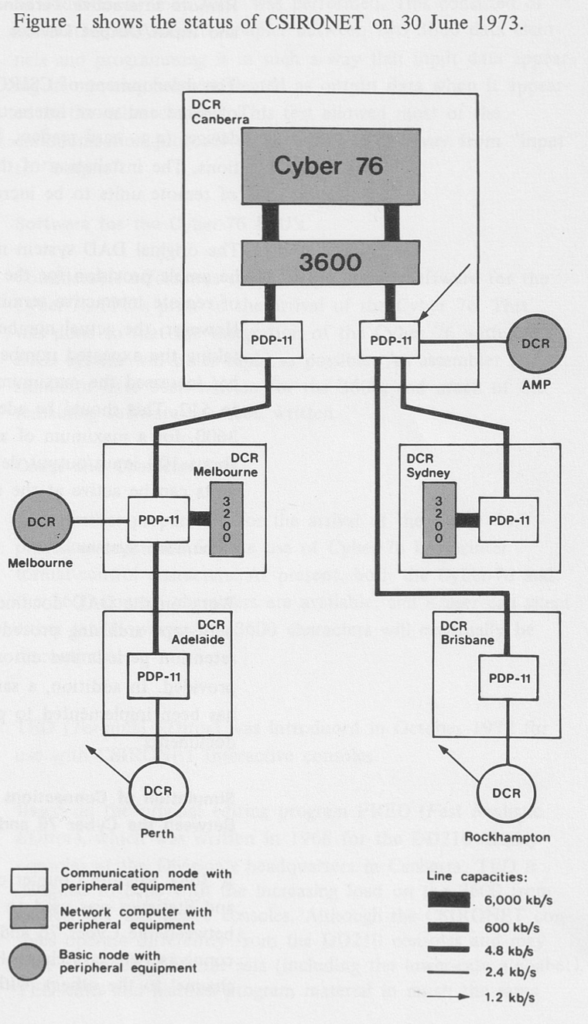

“The communications lines of CSIRONET are currently:”

– 8 links were listed between the mainland capitals and Cronulla, Rockhampton and Townsville, with speeds of 2400 bps or 4800 bps (bits per second).

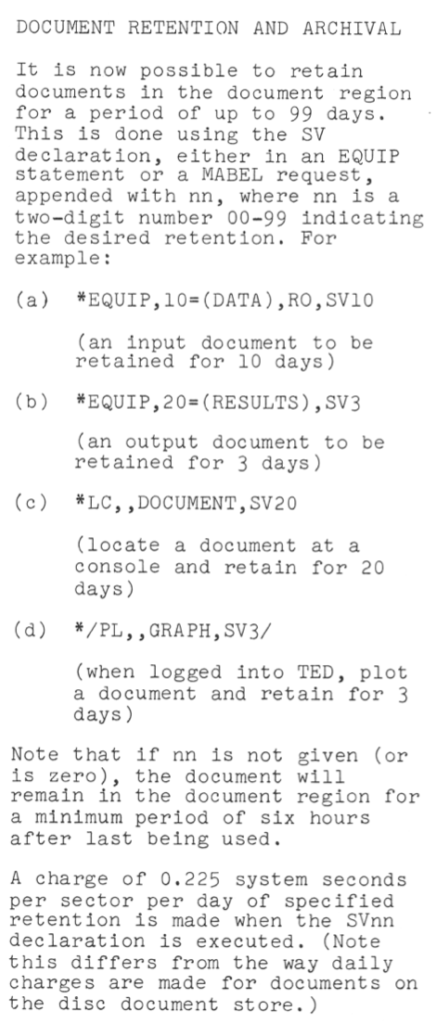

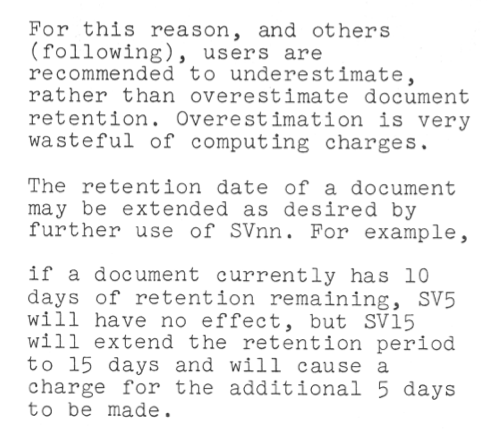

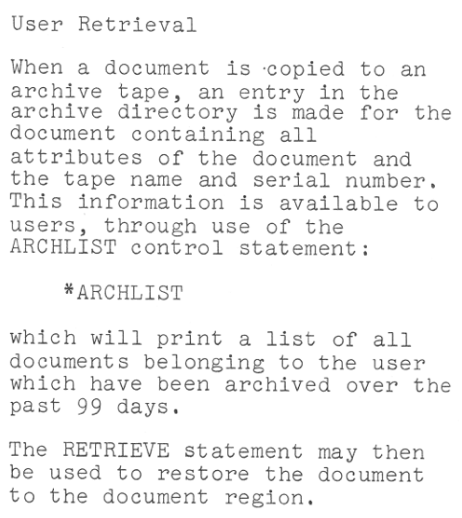

C.S.I.R.O. Division of Computing Research – Newsletter No. 92 – May 1973 contained a lot of information about the upgraded Document Region. Retention periods were introduced for documents, allowing users to specify how many days each document was to be retained. But, there was a sting in the tail: charges for the full retention period were imposed at the time a retention period was specified! This encouraged the use of short retention periods, though these could be extended (with immediate charges for the extended period!).

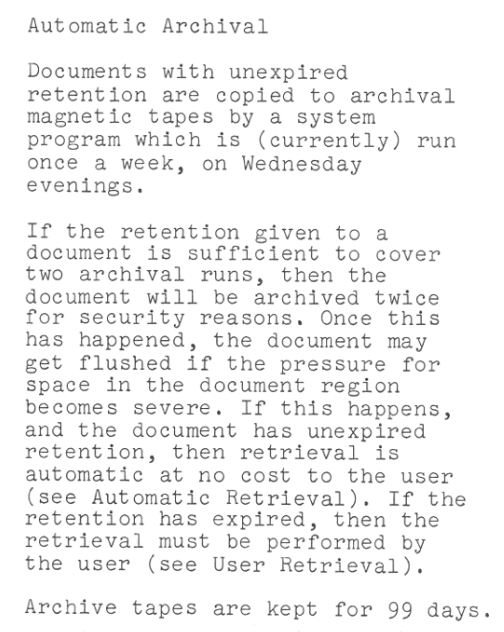

Copies of unexpired documents were made onto tape weekly. If the document’s retention period was long enough, it was copied to two tapes (“for security reasons”). After this, the document may be flushed. These are exactly the HSM processes which are in operation on the CSIRO Scientific Computing Data Store today – migrate data from disc to tape, and free up disc space for migrated files – except that retention periods are not defined, and are taken to be infinite.

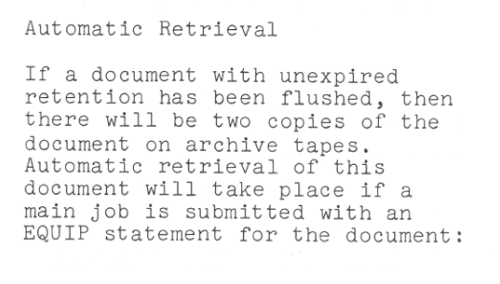

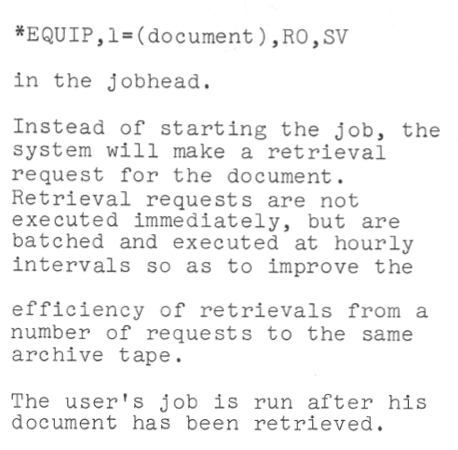

And, here is the counterpart to migration – automatic recall or retrieval. And, there was integration with the job scheduler, and batching of requests for reasons of efficiency.

Finally, users were able to view their holdings in the system, and issue explicit requests for recall or retrieval – the equivalent of the dmget command which has been in operation on CSIRO SC systems from 1991 to today.

And the previous explicit use of the disc storage system was being phased out to make room for the integrated automatic document region.

The following manual was an attempt to make the main manual more accessible!

There was also a quick reference guide to the COMPASS assembler, which also gave information about the instruction set. See here. The Cybers did not have any load/store instructions in the CPUs. Instead, altering the contents of an A register (A1 to A5) resulted in the contents of the corresponding X register being loaded with the contents of the new address in the A register; altering the contents of A6 or A7 resulted in the contents of the corresponding X register being stored in the new address in the A register. Additional hardware did the loading and storing, simplifying the CPU and probably allowing it to run more quickly.

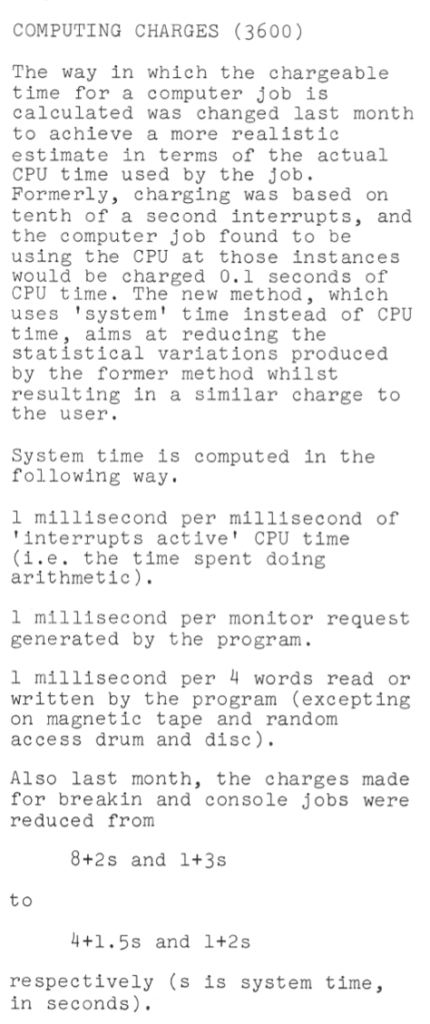

Charging was a recurring theme: this item described revisions which were made to make the charges more realistic rather than relying on sampling.

The 1972-73 DCR Annual report can be found here. Here is the contents page, and the list of branches – now including Rockhampton and Armidale, bringing the total to 10.

There was more information on the Cyber 76, with some details of the major changes to infrastructure to support it.

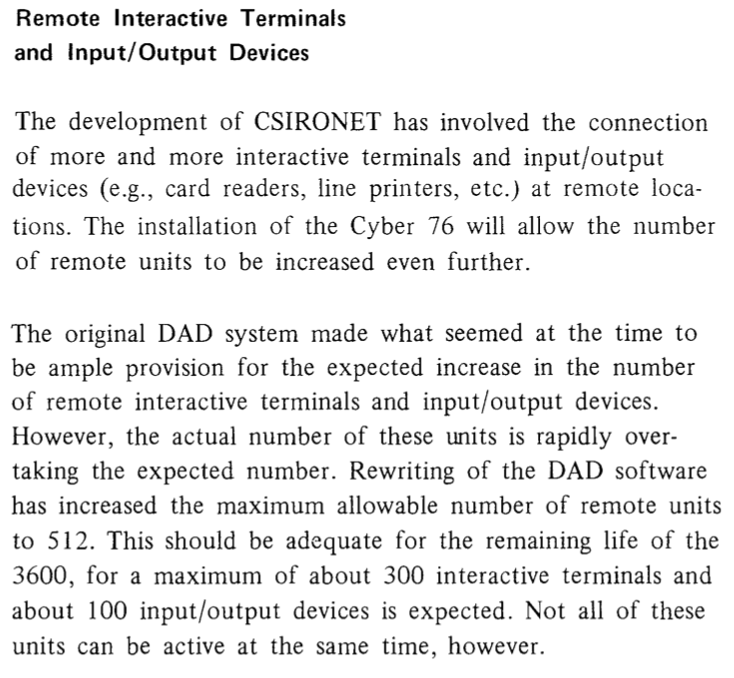

As well as funding for the Cyber 76, funding was in place to expand CSIRONET, so that most Divisions would have remote job entry and interactive access.

As well as funding for the Cyber 76, funding was in place to expand CSIRONET, so that most Divisions would have remote job entry and interactive access.

Development continued on the DAD operating system, primarily to support the Cyber 76 and the growing network

The Document System continued to be enhanced, supporting user-specified retention periods, and automatic retrieval from tape, thus providing one of the earliest Hierarchical Storage Management system.

The FRED editor which was written for the early display consoles, was replaced by TED, which supported a range of terminals, and had extended features.

The last item mentions Ted boxes. These were storage areas within the editor which could store strings of text, useful for copying and pasting text (before copy and paste were invented). However, a key feature was that as commands to the editor were strings of text, these commands could be stored in boxes, and executed like a macro: but these supported one box calling another, and recursion, and many other features. Large software projects sprang up using the features of TED boxes, and one group in Admin. even produced an Ed Programming Language on top of the Editor. Utilities such as permanent file backup on the Cyber 76 were written in Ed boxes. This could be accessed with commands like:

U/PUBLIC/[/PFBACKUP/$

Here’s an example of an Ed box loader – a text file which contained command strings and comments, which TED could process.

f99<99$3(11$12$),99h//98h//16h//14h//13h//12h//11h// f@(j@('wsCjf)('s<gb98<e98$i'98'f=)2=,), C Box loader - skips lines with C in column 1. 11<(ws*j??i'0'lr-99<ji*@-f3's'99'99<z'99'jp'2s,g's:g2b99<c*99$u//99h'size'c*=)?/exiting/2=, C Box to pick up uid, filename, copy file into alternate workspace. 12<z'cycl'i,i'99'i:jf99<^xej('s'99'b3e9b=)13$j^e('ws=20-i'date'i'time'jp98<^oz'98'ows%14$m/],/c*99$)2=, C Box to check whether file has been changed, and if so do some action. 13<99<^xe^ji'99'jf99<^xe^ji'99' C Box to merge 3 lines, starting on the middle line, leaving the last line in 99. 14<j-i;1+;98<98t'98'98>ji%^jl('s0jp) C Box to do counting. 16<c*3e17$ C Box to resume after failure. 17<2(o('s;f99<;=)c*)@=,10<10$10h// C Box to redo without copying file again.

Here’s a partial explanation of the above.

Forward, then load the contents of the line into box 99 and execute box 99 (which now contains f@(j@(‘wsCjf)(‘s<gb98<e98$i’98’f=)2=,), .

This moves forward again, and then loops:

Go to beginning of the current line, loop again, looking for a C in column 1 (I think the ‘ restricts it to thecurrent record, and the W to column 1), and if found justify and move forward. Exit the loop if it fails to find a C in column one of the current line………….then search for a < in the current line, and, if found split the line after the < sign, go back, load the box number and < sign into box 98 (11<), erase that line, and then execute box 98 to slurp the next line into box 11. Then insert the contents of box 98 back at the beginning of the line and move forward and skip to the first comma, …….

This was all in relaxed mode where delimiters could be omitted from commands like search ( s/text/ ) if the text was a single character.

In the Terry Holden collection there is a scan of the TED manual from January 1974 – “TED – DCR Text Editing Program.pdf”. The manual is available here. There were Ed (the successor to Ted on the Cyber 76) programming contests!

Some primitive level of security was introduced.

Here’s an insight into the challenges of writing software for the PDP-11s that were used as nodes on the network – all in assembler, and cross-compiled from the Cyber 76.

Back to start of 1972-73 Back to top

1973-74 – DCR, Cyber 76 in service: links, porting apps, permanent file management; CSIRONET: 30 nodes, delays in lines for network, Remote Access Group; AI, 3200s removed, building extension announced

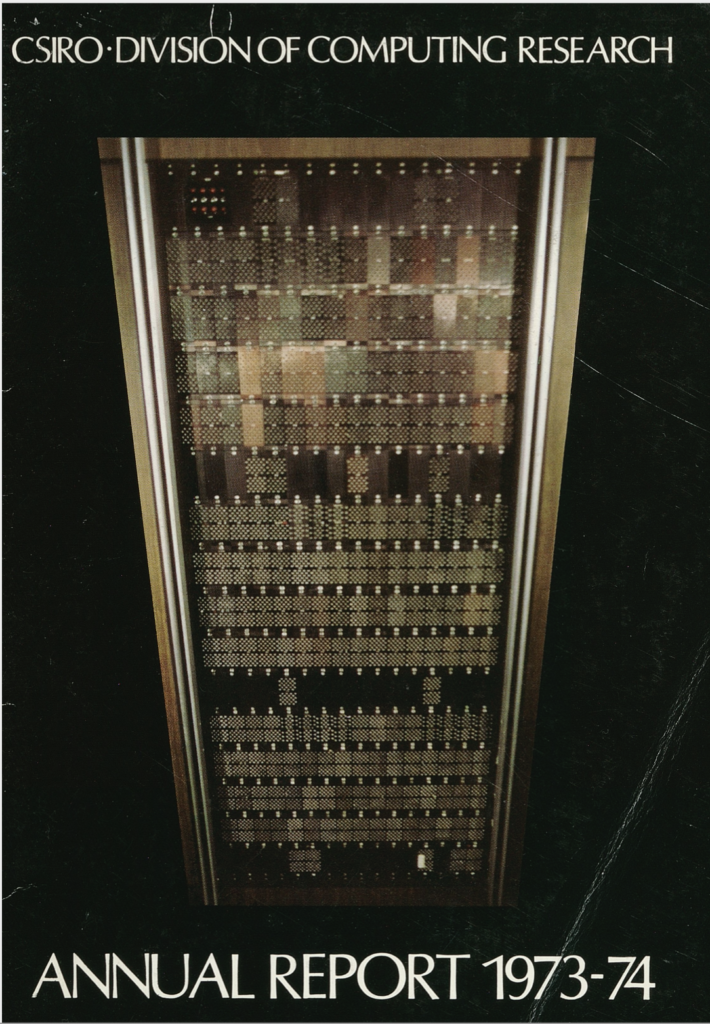

The 1973-74 DCR Annual report can be found here. Here is the contents page (the number of branches remained unchanged).

The introduction more than hinted at the difficulties faced by the Division in bringing the Cyber 76 into service: chief among these were the work faced by users in converting to the new machine. (In a conversation in April 2020, Peter Heweston mentioned that each CDC machine came with a new operating system that required users to convert what we now call apps.) At that time, IBM was settling on one OS, and in later years we have the near duopoloy of UNIX/Linux or Windows.) Further problems arose from delays in the provision by the Post Office of transmission lines, the problems of maintenance of the PDP-11s being used for intensive communications tasks, delays to new accommodation and staff shortages. On a positive note, the year was the first of a three-year expansion program, and Regional Computing Committees were set up. Finally, the introduction included the goal “to provide the Australian scientists a computing service comparable to the best in the world.”

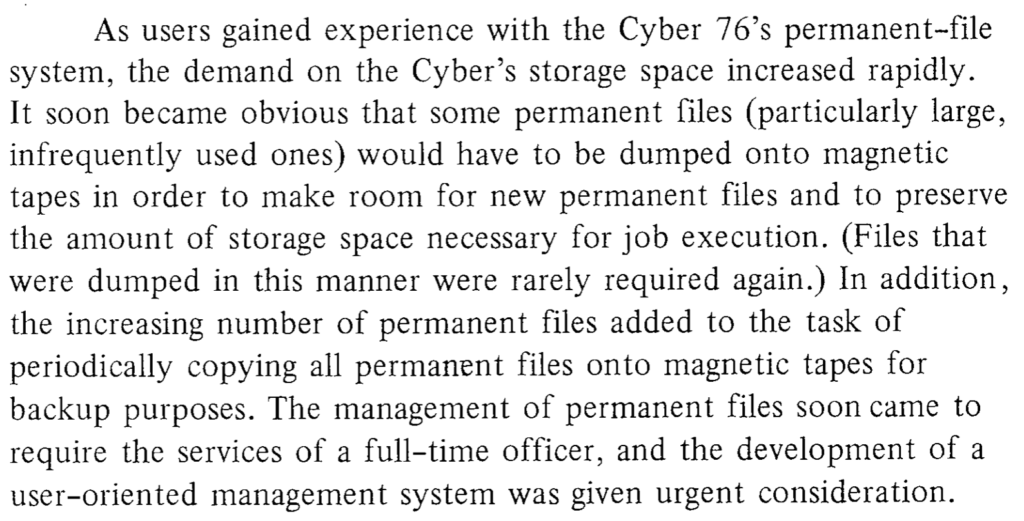

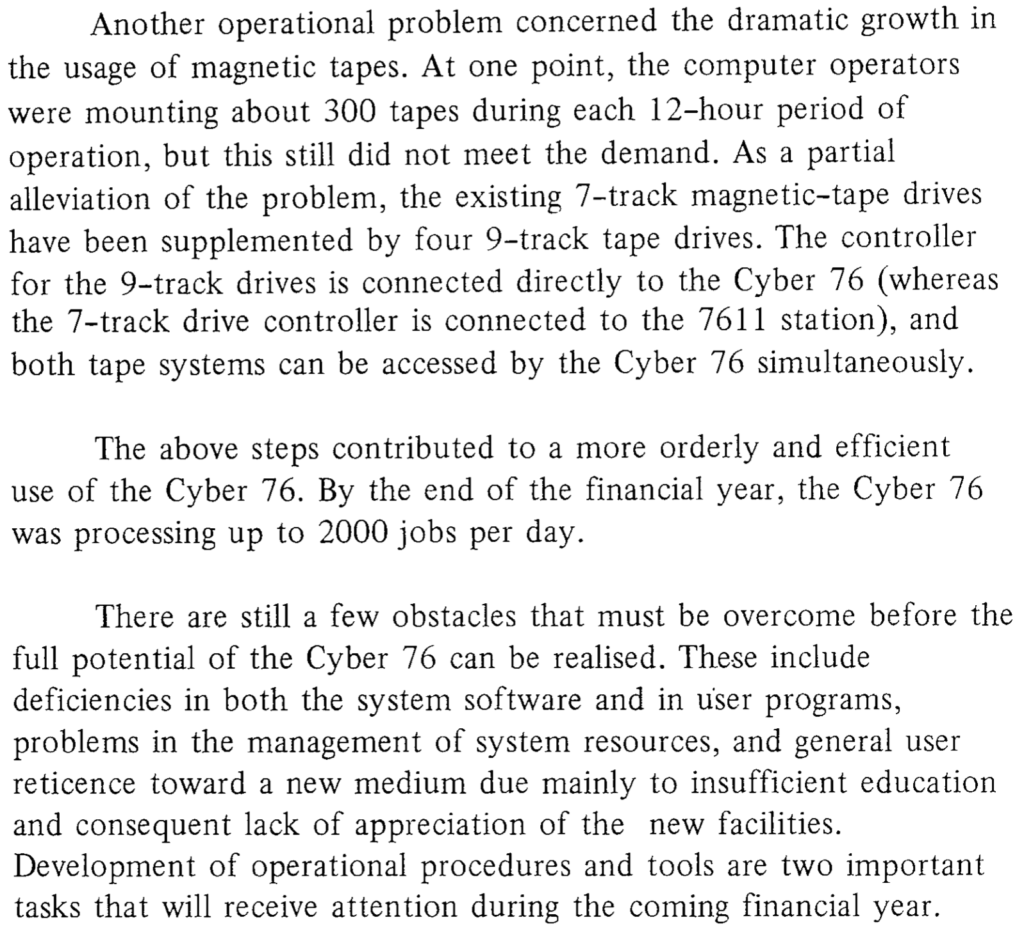

Under the heading “New Equipment, Services and Software” was an item on Operational Development of Cyber 76. This describes the transition from a magnetic-tape regime to channel connection to and from the 3600, which acted as a front-end. It also describes pressure on the permanent file system, almost from the start.

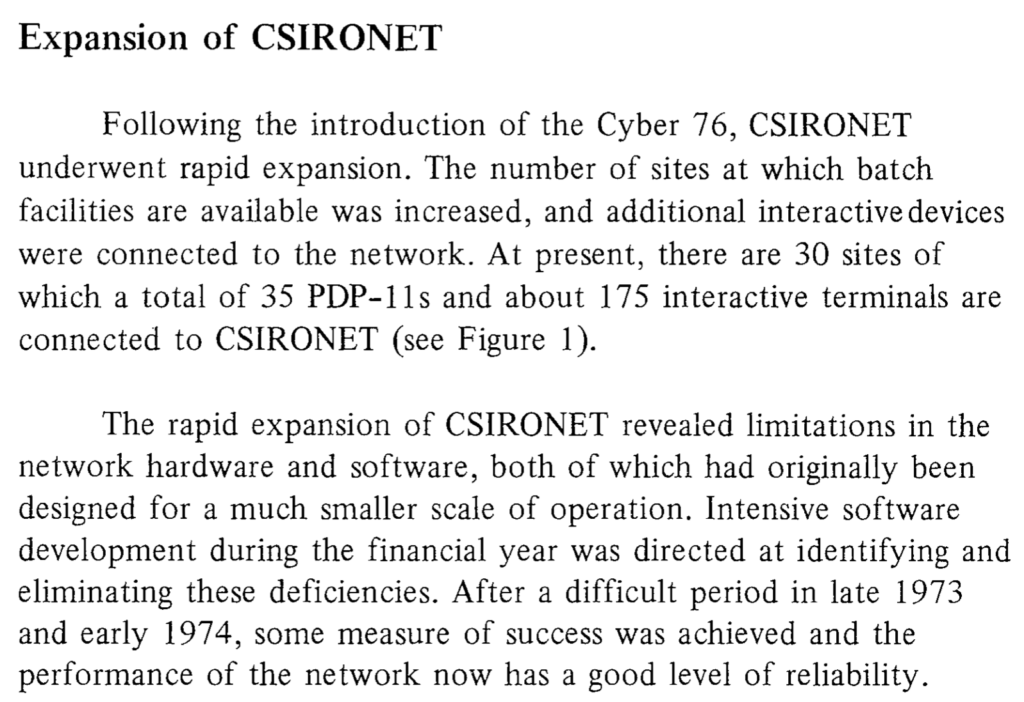

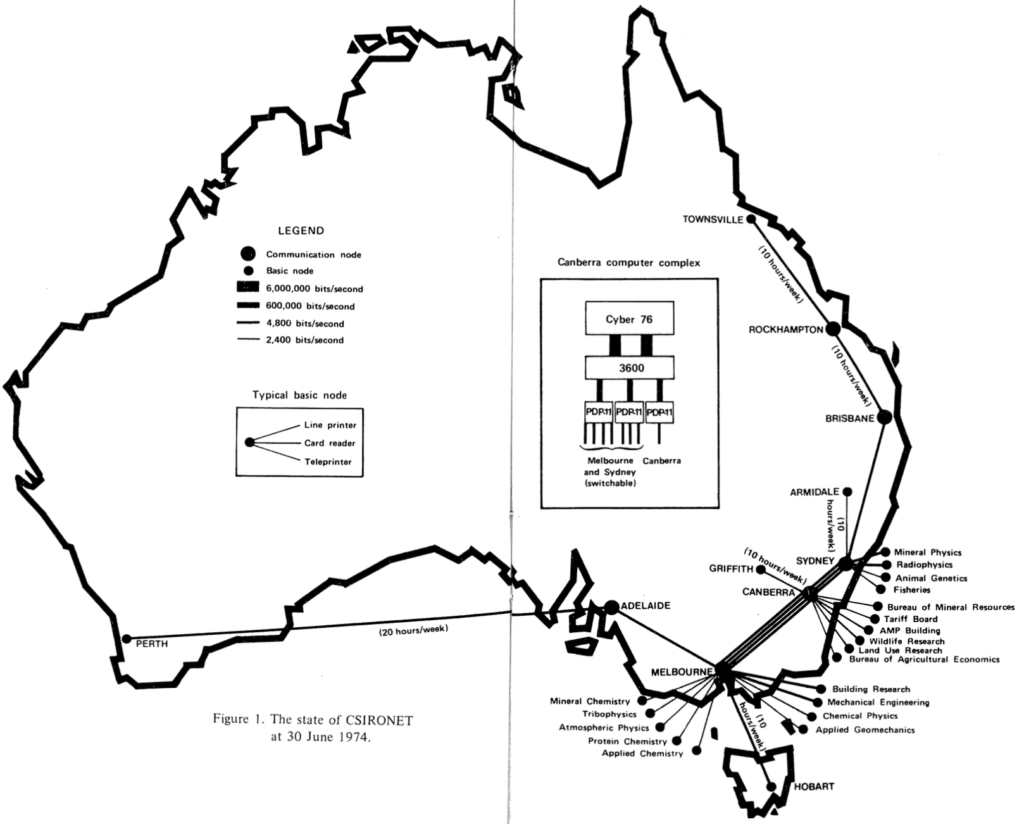

Also described was the expansion of CSIRONET.

Documentation took advantage of the new technologies – there was no what-you-see-is-what-you-get visual access though.

After the arrival of the Cyber 76, a weekly on-line newsletter called CYBARITES was provided.

Interactivity with the computers was enhanced with the ability to run jobs on the Cyber 76 directly from the TED editor (running on the 3600), with output returned to the editor. The charging rate was about triple the rate for batch processing!

The growing importance of the network led to a separate group being formed.

The growing importance of the network led to a separate group being formed.

Several projects were described under the Research section. This one, about bushflies, harks back to CSIRO’s work on developing insect repellant after flies annoyed the Queen on a visit to Australia.

Several projects were described under the Research section. This one, about bushflies, harks back to CSIRO’s work on developing insect repellant after flies annoyed the Queen on a visit to Australia.

Database systems were in their infancy, but DCR was heavily involved in providing access to such systems, albeit in a manner that would be considered unusual these days – through Fortran!

And, given the current emphasis on machine learning and artificial intelligence, it is an indication of the pioneering thinking that DCR co-sponsored a 5-day symposium on AI in 1974!

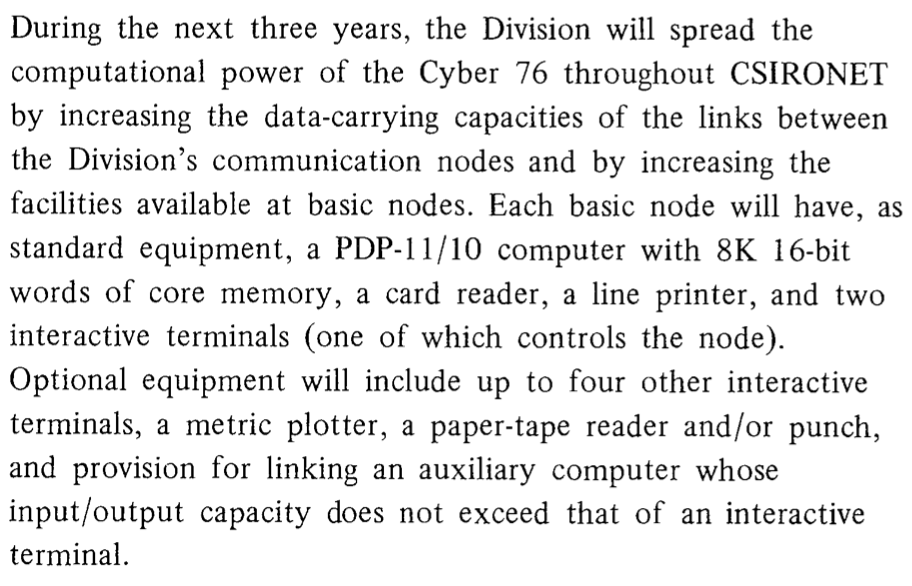

Under the “Summary of Computer Equipment” section, the definition of a basic node of the CSIRONET network was noted.

The report noted that ‘The 3200s were removed by October 1973.” They were in service for about 9 years. There was no other mention in the annual reports of their demise, although the previous year’s report mentioned that the 3200s had been connected to CSIRONET.

The report noted that ‘The 3200s were removed by October 1973.” They were in service for about 9 years. There was no other mention in the annual reports of their demise, although the previous year’s report mentioned that the 3200s had been connected to CSIRONET.

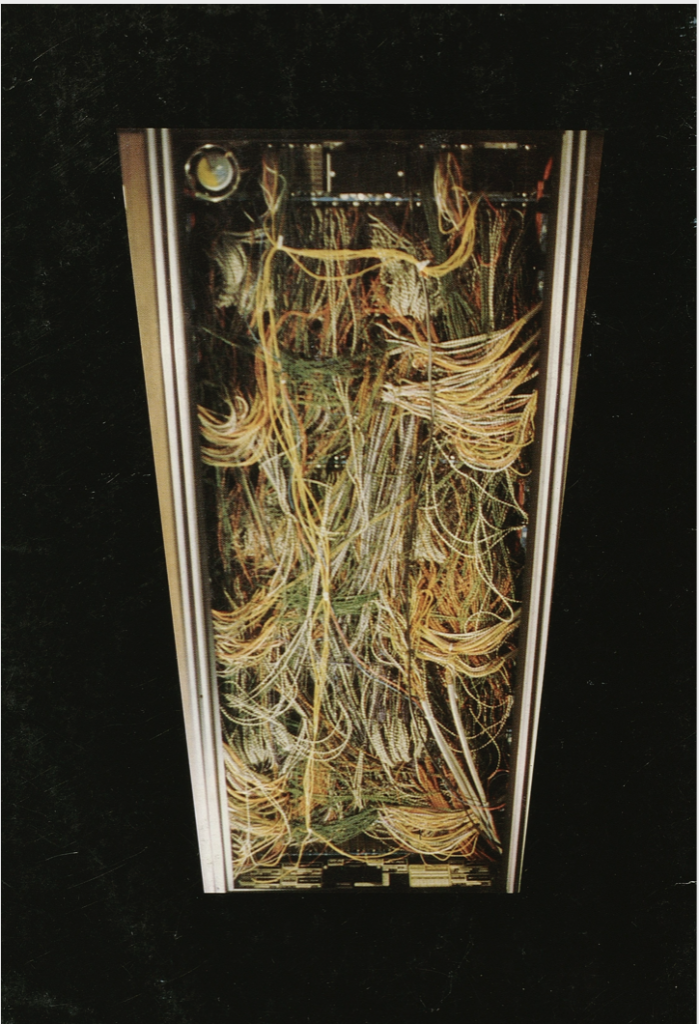

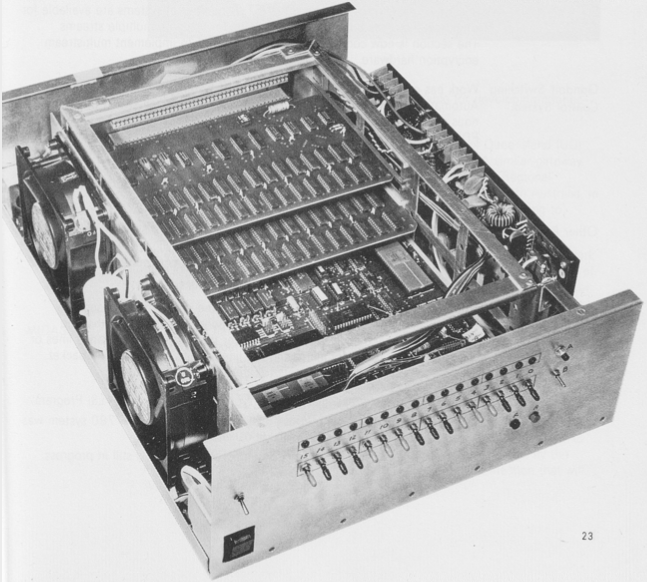

Finally, the front cover showed the front of an unnamed equipment rack. The back cover showed the rear of the cabinet, showing the huge bundles of wires.

Back to start of 1973-74 Back to top

1974-75 – DCR, COMp80 in service: microfiche, image processing, Hobart branch, Cyber 76 low MTBF, non-CSIRO usage reaches 40%, CSIRONET: 50 PDP-11 nodes, 48 kbit/s trunk lines, custom host-network interfaces

The 1974-75 DCR Annual report can be found here. The front cover featured a satellite image

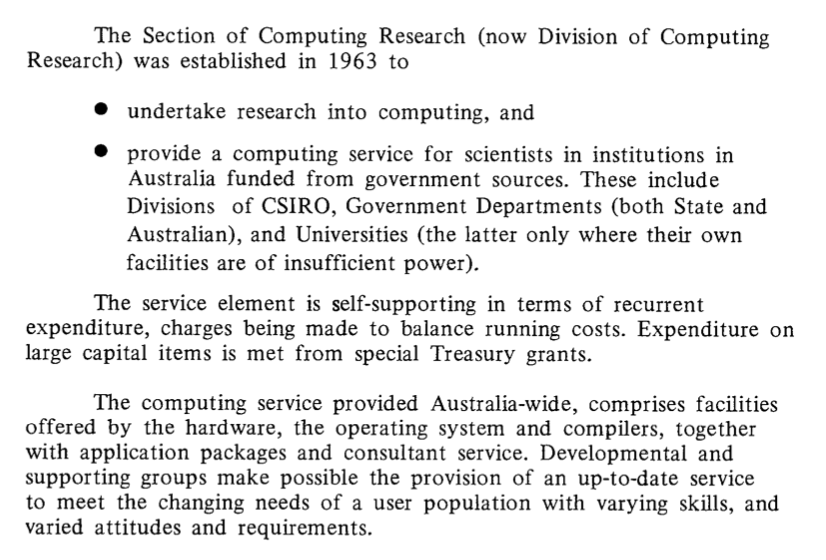

A prologue set out DCR’s charter, and had a curious reference to ‘a user population with varying skills, varied attitudes and requirements’. I had joined CSIRO at this stage, so might have been covered by this statement!

Here are the contents. (The number of branches increased by one with the addition of Hobart, bringing the total to 11.)

There was again a long introduction, but this year’s one was attributed to G. N. Lance Chief of Division. Progress was being made on the building extension.

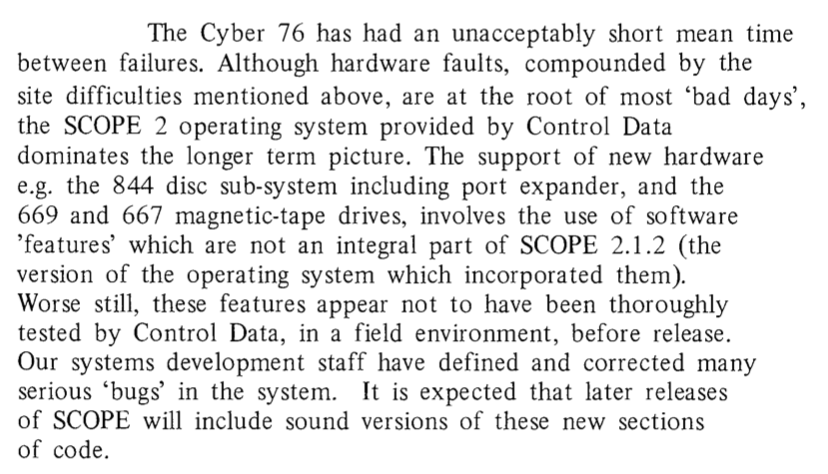

The Cyber 76 was at least more reliable than the CDC 6600, which reportedly had a MTBF of 17 hours! With Seymour Cray’s design goal for each machine to be ten times faster than its predecessor, reliability was not the main goal. And, the SCOPE 2 OS was a special for the 7600/Cyber 76 – the first 7600s were delivered with no operating system, which was the responsibility of the customer. See CDC 7600 at wikipedia: “Both LLNL and NCAR reported that the machine would break down at least once a day, and often four or five times.”

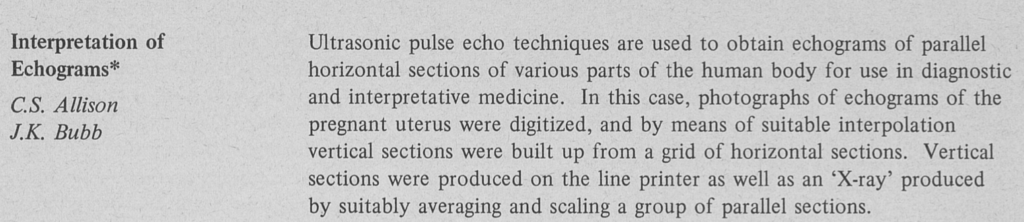

The coming of the COMp80 brought a revolution in the ability to store output and produce large volumes of graphics.

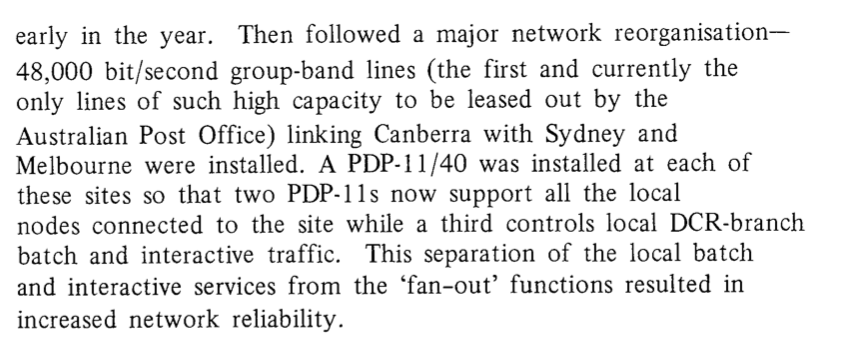

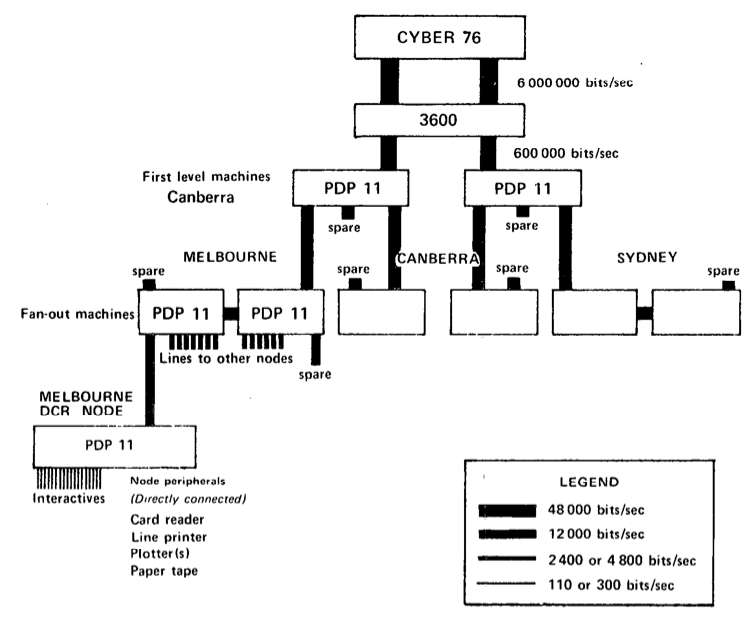

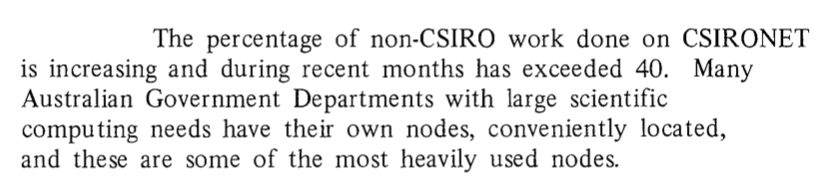

CSIRONET (the network) continued its evolution, with 48 kbit/s inter-capital links, and all sizable user groups having an on-site or nearby node.

DAD and the 3600 continued to support interactive and central input/output facilities.

From its inception as the C.S.I.R.O. Computing network, access was to be provided to government departments, and it was noted that non-CSIRO work had reached 40% of the total. This may be the start of the difficulties CSIRO had within its charter of reconciling its research and application roles with providing a service to others which was not part of its mandate.

The introduction finished with an expression of hope that the Cyber 76 will become a computer on which reliable interactive computing is feasible, and this was to unfold within a couple of years.

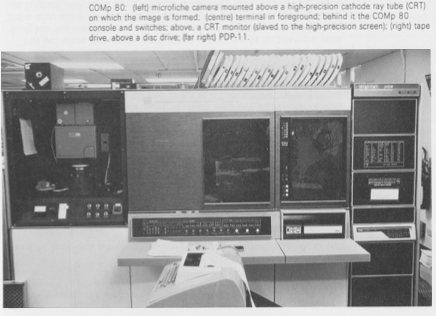

Under the New Equipment section, more details of the COMp80 were given. (A later section provides more information on the use of microfiche.)

Here is an example of DCR staff needing to modify SCOPE 2 to support expanded storage. This was also the beginning of having additional on-line storage under user or group management – no backup, no restoration in the event of loss, no flushing, but putting the responsibility back onto a group of users.

The business of managing data on unreliable media with unreliable reading and writing devices is so far removed from the storage services available to today’s generation. This item notes improvements with newer equipment.

CSIRONET continued to expand in size, in speed, in resiliency and reliability.

DCR continued to embark on targetted hardware development to support its unique network. The last paragraph hints at future developments to replace the 3600’s roles.

Managing shared storage areas continued to require attention, this time on the Cyber 76

By 1975, Csironet was well established. A paper by Colin D. Gilbert, The Evolution of Csironet, noted that:

The paper included a map showing the extent of coverage and the connection path from the Cyber 76 to a sample node:

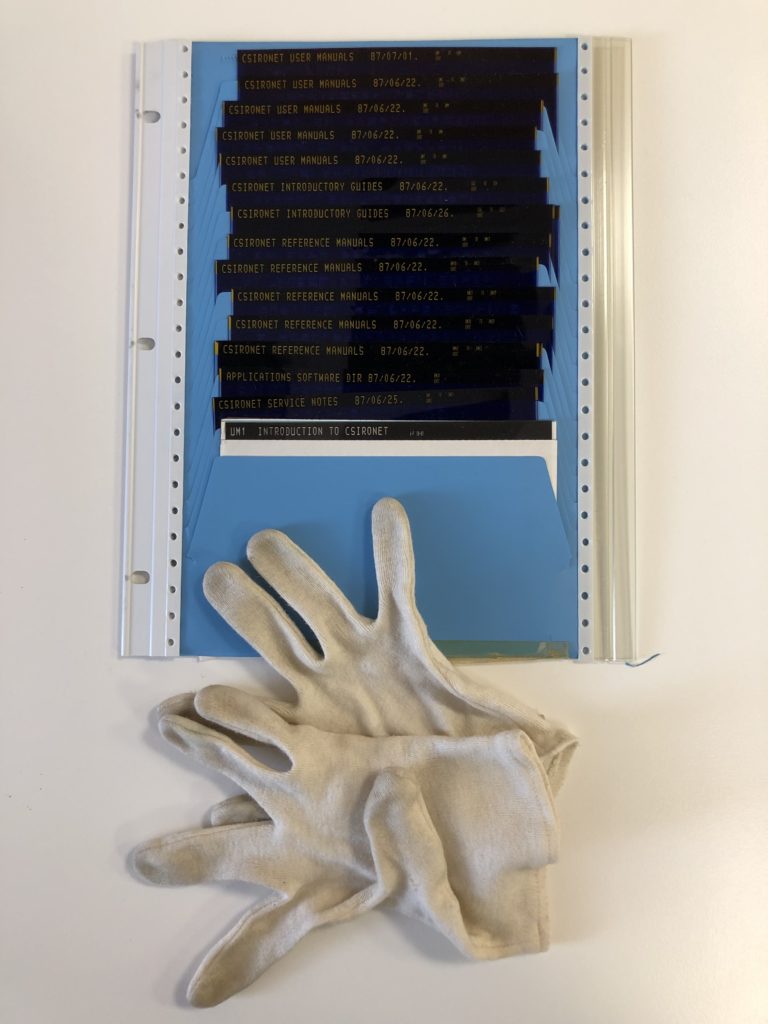

The January/February 1975 Newsletter announced that a “COM Unit is Ordered”. The installation was announced in July 1975. The COMp 80 provided output to microfilm, microfiche, 35 mm film and bromides. Microfiche became the default way to store large amounts of output for Csironet users.

Here is a picture of some microfiche, with a ruler beside to show the scale:

If you zoom in on the picture on the left hand side, you could see that each fiche contains images of hundreds of pages – the capacities were 420 A4/quarto size, or 280 11″x15″ line printer page images. The upper fiche is an original, and the lower one a duplicate, which cost only a few cents more. These were read with a reader/viewer, like this one:

Most staff heavily involved in computing had ready access to a viewer, and many had their own on their desk.

Microfiche was a revolution in enabling large quantities of output, including text and graphics, to be stored for reference. Microfiche was ideal for distributing user documentation economically: for the first time, each user could have access to all the documentation (which at this stage was far too large to be stored on-line!). Here is a picture of microfiche making up most of the Csironet documentation from 1987, stored in a special holder in a loose-leaf folder. If you cared about the originals, you would use the cotton gloves pictured, to preserve the contents if they were to be subsequently duplicated.

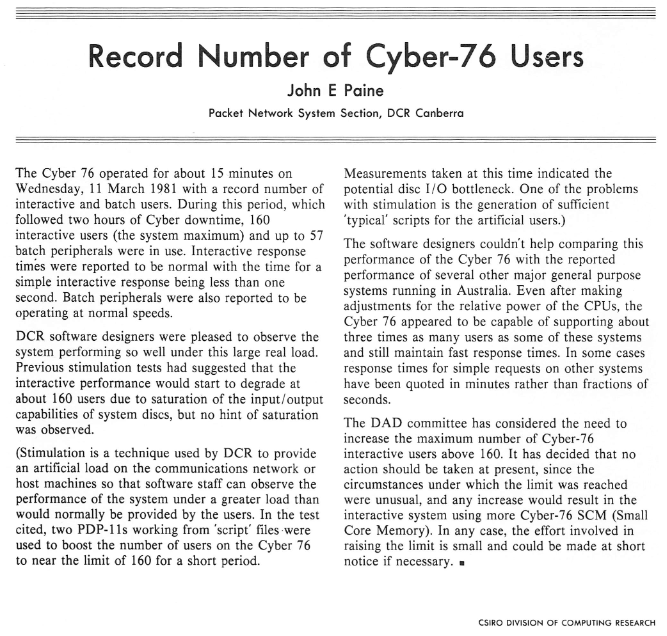

There were plans to install two CDC Cyber 172s to take over the front-end role of the 3600 (DCR Newsletter 104, June 1974), but these plans were abandoned (see the Future Prospects paper by Peter Claringbold from April 1975). Instead, the 3600 continued in service for several more years, extra LCM was installed on the Cyber 76, and an interactive subsystem (CYI) was built to run on the Cyber 76, along with a new version (Ed) of the TED editor. How successful this project was is demonstrated by the report in the Csironet News no. 158, p20, April 1981. The system supported 160 simultaneous interactive users, with no apparent degradation in performance.

Back to start of 1974-75 Back to top

1975-76 – DCR, building extended, Fernbach report, non-CSIRO usage 50%, CSIRONET: 43 nodes, multi-host development, peripheral driving, NODECODE exported; preparation for 3600 end: Cyber 76 and node enhancements

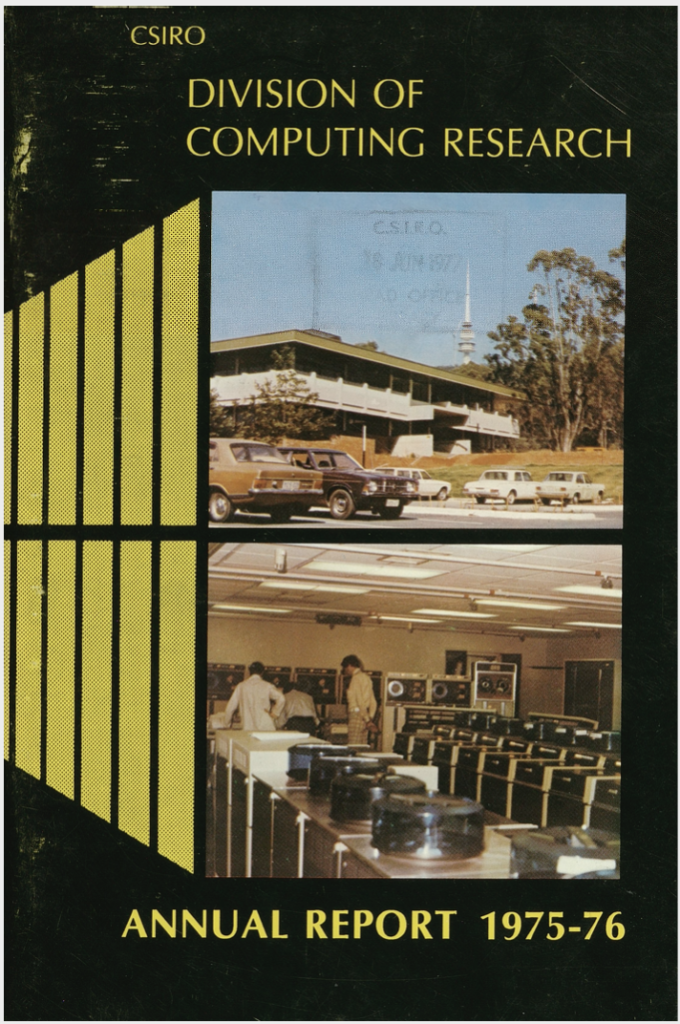

The 1975-76 DCR Annual report can be found here (78 pages). The front cover showed a view of the building with the newly-completed office wing, and a view of the computer room.

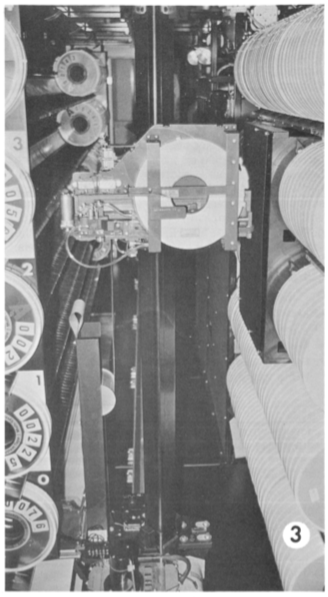

The foreground shows rows of CDC model 844 disc drives which featured removal disc packs. There were 31 units, and each disc pack had a storage capacity of 118 million characters (88.5 Mbyte). The background shows magnetic tape drives.

The Division’s charter remained unchanged since its inception, and was re-stated:

There followed a list of applied research areas undertaken by the Division.

The next paragraphs went on to describe how the service addressed the needs of scientists.

The above covered the activities of the Division, but gave a glimpse of the need to continue to emphasise the research as opposed to the purely service role, which was the majority of its activities, but was not a role that was core to CSIRO’s charter. As I saw it, this tension remained to the end of the Division, when it was split into the service arm Csironet and the Division of Information Technology.

The Chief’s report then followed, with a fairly pointed criticism of the framework under which the Division was constrained.

The Fernbach report was one of many over the years.

The following observation highlighted a milestone in the growing proportion of the computing done by non-CSIRO users: unless this was considered part of CSIRO’s mandate to help industry, it was not CSIRO’s core business, and in any case, most of the non-CSIRO usage was from government departments.

More storage was acquired, and Csironet continued to grow. The CDC 3600 was clearly nearing the end of its life, but was a core component of the network and services. Many of the subsequent pages of this annual report highlighted work underway to replace this functionality with services run primarily on the Cyber 76 under SCOPE 2, which was never designed for such interactive, network-focussed, real-time, and direct user interaction. It was a challenge.

Some of the new facilities under development included:

- a simulator for the Cyber 76 SCOPE operating system, allowing the withdrawal of the 16:30 test period

- development of a Cyber 76 Peripheral Processor programs to interface with CSIRONET – batch, interactive and test

- development of a ghost station on the Cyber 76, to replace the 3600

- integration of local modifications (23,000 lines) into each new release of SCOPE

- development of Cyber 76 replacements for TED (interactive) and RIO (remote input/output). These were developed as user-level jobs, with additional locally-implemented privileges

- the creation of an event processor, which allows messages to be passed between jobs

- development of the Cyber 76 hardware Maintenance Control Unit to allow it to be used for software maintenance and as an operator console.

- automated pack assignment

- automated tape label writing

- magnetic tape reservation

- magnetic tape audit and inventory

- accounting changes, including showing itemised resource usage and cost for each job – see the example Cyber 76 job dayfile listing at here.

- generalisation of the accounting systems

- interactive preprocessors, particularly for Document Region (3600) and permanent file (Cyber 76) backup

- generalisation of CSIRONET, to support multiple hosts (not just the 3600), and to provide connection to the Cyber 76 as one of the hosts

- connection of the COMp80 to the central hosts

- System Performance Analysis and Resource Monitoring

- Reference Indexing Interrogation

The last item (by Peter Hanlon) involved the development of an indexing tool to collect keywords from publications and store them and their location in a database. For example, the Users’ Guide of some four hundred pages yielded an interrogation file of approximately fifty thousand words. Querying this typically took 20 milliseconds of CPU time. This is a local version of Google search, 20 years before its first search capability in 1996!

And, here is another export success:

Here’s another major piece of work allowing the network to become multi-host:

Research work was reported. Two items of particular interest were the modelling of social welfare policies, and modelling of carbon flow in an estuary to understand the ecosystem.

Terry Holden reported on the Review of Computing Services by Dr S. Fernbach. The summary of the report’s findings were included. (The full report is in the Terry Holden papers). Here is the summary.

This addresses some of the users’ concerns – “failure of DCR to provide reliable, stable and adequate computing support”, and lack of “hardware and software” desired by users. Some of the solutions involved additional funding and a 50% increase in staff, which never eventuated (see the graph of DCR staff numbers, which shows a decline in staff numbers for each of the next three years!)

Back to start of 1975-76 Back to top

1976-77 – DCR, Chiefs: Claringbold replaces Lance, 3600 nearly phase out, COMp80 direct connect, typesetting, standalone Cyber 76 system, Ed replaces TED

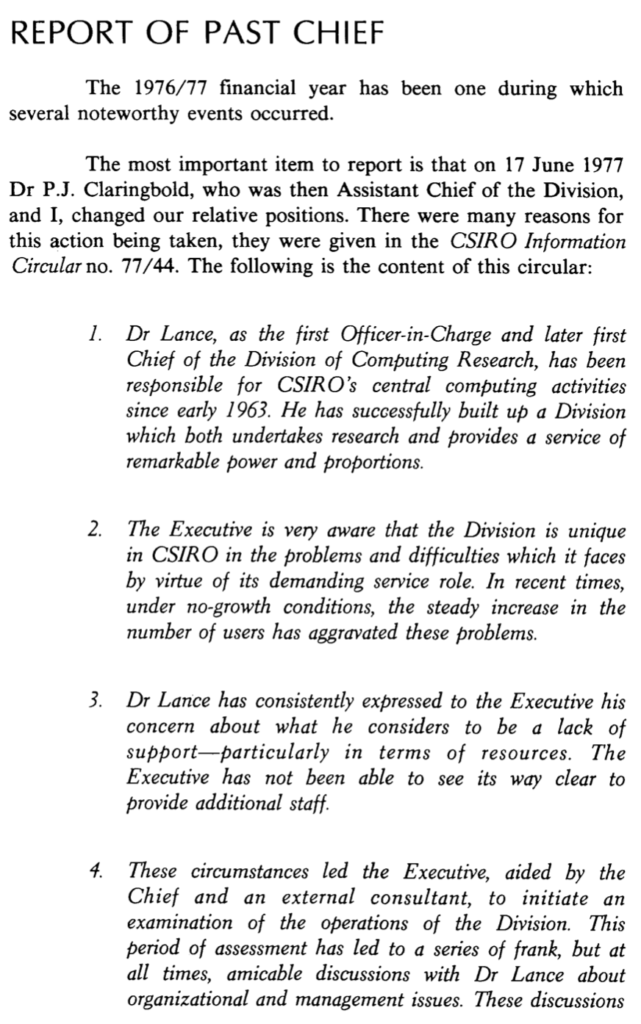

The 1976-77 DCR Annual report can be found here (89 pages). The contents were similar to previous years, except the report started with “Report of Past Chief”, given below in full.

Thus in 1977, Godfrey Lance handed over the Chief’s role to Dr Peter Claringbold, following the failure to gain more resources from the CSIRO Executive to meet the growing service load. To what extent he was forced to do this may remain unknown. He remained as Assistant Chief in charge of research, but departed soon after. He was at the Avon Universities Computer Centre, Bristol, UK in October 1980 (csiro dms Newsletter no. 70, November 1980), and lived in Bermagui NSW in retirement. He died in 2020 – see obituary.

This was a watershed time on the history of the Division. Godfrey Lance went public through newsletters and annual reports with his frustration with the CSIRO Executive, which would not have been well received.

General access to the CDC 3600 was disabled in May 1977, with most of its functions by then transferred to the Cyber 76.

Apart from the Chief change, the major work reported was headed by:

With the COMp80 now in production and on-line to the Cyber 76, typesetting became a major new service.

Picture processing was enhanced with the relocation and expansion of a PDP-11/40. To help with software development, Don Fraser wrote a Fortran version of the DCR Ed editor – I have a copy!

... C THIS PACKAGE IS WRITTEN IN PDP11 FORTRAN TO PROVIDE, IN A SHORT TIME,TED 60 C A MINI TEXT EDITOR WITH GENERALLY THE SAME COMMAND STRUCTURE AS 'ED',TED 61 C HENRY HUDSON'S EDITOR FOR THE CSIRO CYBER 76 COMPUTER. TED 62

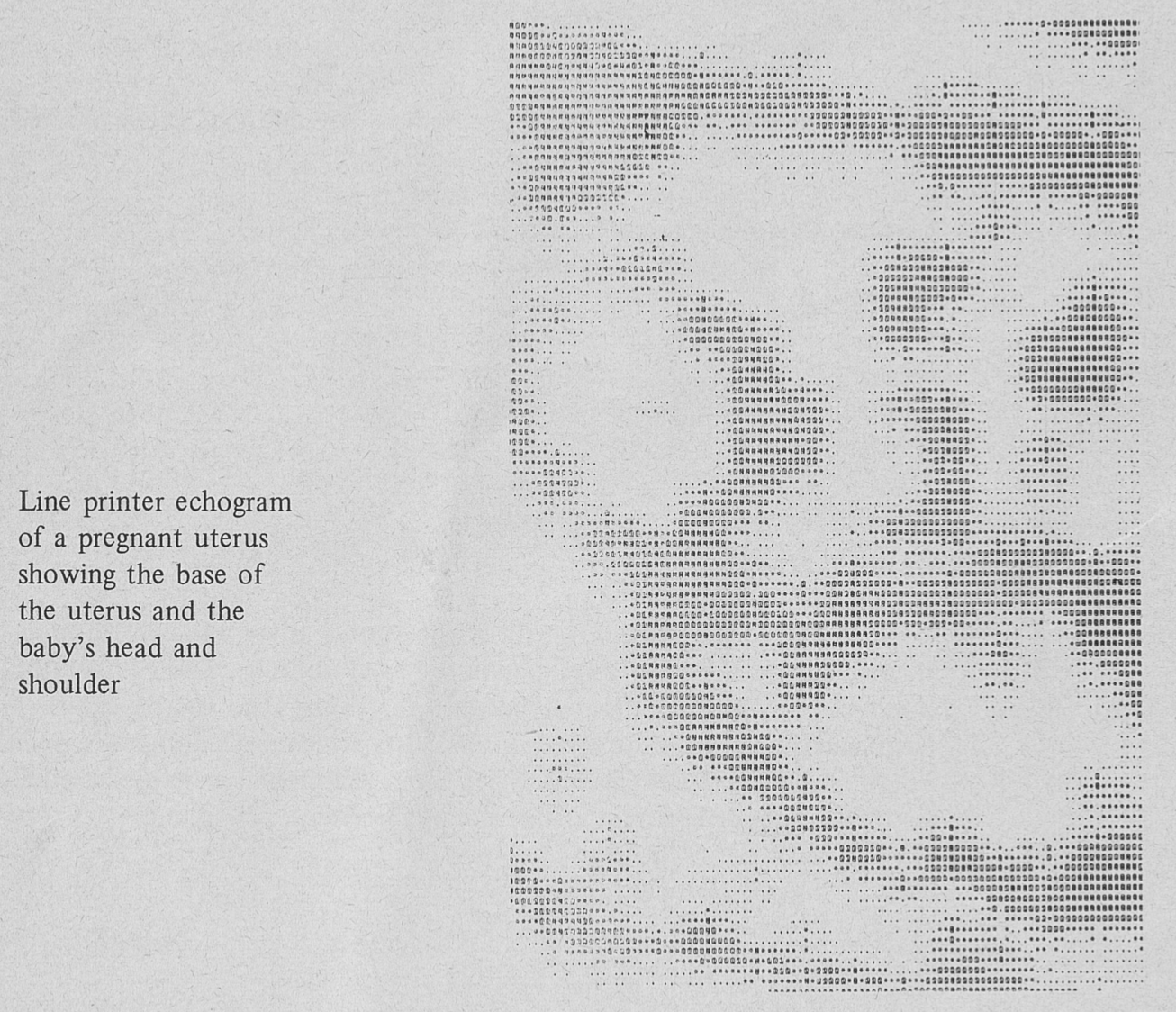

Here’s an example research project using the picture processing capabilities.

Here’s another interesting application!

The Summary of computing equipment reported 392 connected terminals, 6 dial-up ports, and 18 auxiliary computer connections. It listed the nodes and the equipment at the DCR-managed ones. One of the nodes was at the Reserve Bank in Sydney.

The Summary of computing equipment reported 392 connected terminals, 6 dial-up ports, and 18 auxiliary computer connections. It listed the nodes and the equipment at the DCR-managed ones. One of the nodes was at the Reserve Bank in Sydney.

Back to start of 1976-77 Back to top

1977-78 – DCR, 3600/DAD/Document Region decommissioned; 2500 users, Birch report: cost recovery and maximising usage, rationalising Divisional computing, rationalising government-supported scientific computing; improved reliability, CSIRONET: 68 nodes; new computer hall in preparation

The CDC 3600 system was de-commissioned in the second half of 1977. One of the features was the DAD operating system, written by CSIRO and Control Data staff members. It included a Document Region – this was a storage area with multiple levels and automatic transfer of data between the levels – the drum, disc, and operator-mounted tapes (7-track), and so was an early Hierarchical Storage Management system from 1973, with automatic recall of off-line files and integration into the job scheduling.

The 1977-78 DCR Annual report can be found here (80 pages – original was 76pp + covers, but some pages are repeated and pairs of landscape pages are rendered as single pages. Pages 1-34, then 43-44, then 33-76 are present).

The introduction highlighted DCR’s mission. It continued to have a mandate to meet the scientific computing needs of institutions funded by Government. This foreshadowed in some respects the role of APAC and NCI, though their remit included more specifically the university sector. A total of 2500 users was a significant community.

There was an expanded contents section, with major headings for the research areas.

The Chief’s review commenced with notes on new policies, which came from the recommendations of the Birch report.

Recommendation 80 affirmed cost recovery, but added the rider of seeking to maximise usage. This led to changes, reported below, to open up the systems outside business and attended hours, and striking a much lower charging rate for this.

Recommendation 81 attempted to constrain the acquisition of local computers, and was doomed to failure. I remember Art Raiche telling me that when his Division acquired their own minicomputer, they could afford to make mistakes and could do science again. The attraction of owning a bright shining object, and having it available for instant gratification without the strictures of batch systems and queuing and under local management, was very powerful, and still is!

Recommendation 82 attempted to bring centralisation to academic scientific computing, and was again doomed. It was another 20 years or so before the universities agreed to a consortium, driven by government funding to APAC and NCI.

Recommendation 83 tried to confine DCR’s research efforts to areas that users desired. However, with 2500 users, that was also doomed. It wasn’t until the mid-1980s that DCR was split into the Division of Information Technology and Csironet for the separate roles of research and services.

It was frustrating as a user in those years to have the experience (it seemed frequently) of losing the current work when the network or host system failed.

It was frustrating as a user in those years to have the experience (it seemed frequently) of losing the current work when the network or host system failed.  DCR worked on providing better reliability, and the Cyber 76 version of Ed could recover an editing session if the Cyber 76 or network went down (planned or

DCR worked on providing better reliability, and the Cyber 76 version of Ed could recover an editing session if the Cyber 76 or network went down (planned or

unplanned).

The above addressed the issue of costs, asserting that CSIRONET’s charges were lower than comparable services, and they probably were. But, scientists crave freedom of access to facilities, and are reluctant to spend on things that they can acquire freely. So, for example, some scientists in this era chose to go to other institutions, for example NCAR in Boulder Colorado, since access to the computing services was free there.

Here are some of DCR’s actions to help with the aim of maximising usage (while still retaining revenue. Many Divisions and user made heavy use of the non-prime-time regime with its considerably lower charging rate.

Here are the job request lines from a couple of Cyber 76 jobs from this era – in the early 1980s, lower case was supported:

r50b(P0017,T20000,ms120000,dab00) <<<<< Robert Bell >>>>> RUNG21E(P0111,T20,DAB01) <<<<< ROBERT BELL >>>>>

The first job was a main run, requesting 20000 (octal!) seconds, and a priority of 0017 – again octal, and taking advantage of the priority zero rate. The second job was a post-processing job, with a higher (but still low) priority. Both jobs could be submitted together, and because of the dependency specification, the second job would not start until the first job had signalled that its data was ready with a statement like transf(rung21E).

The passing of the CDC 3600

Both the Communications Systems Group and the Csironet network continued to expand, with staff now numbering 13, 68 nodes in operation, 584 connected terminals and a growing number of PDP-11s in service.

Support for card punches and cassette tape drives on the network were new items, illustrating the passing of the old and the introduction of consumer storage devices, allowing a maximum of 263000 characters per side.

A User Assistance Section was formed, led by Barry McDowell, with one other staff member.

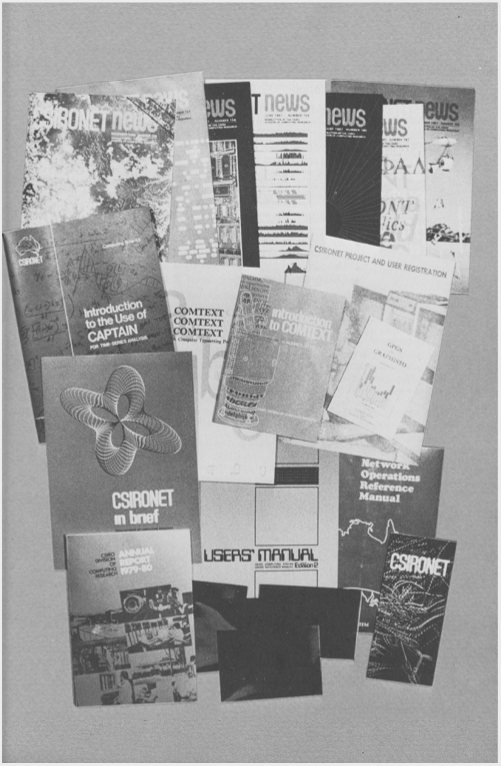

The Documentation Section was expanded from 4 to 6 staff. Microfiche was being used extensively to allow updated documentation to be produced and distributed cheaply to users. There were three series of publications: Computing Notes, Services Notes, and DCR Manuals. The newsletter was changed from monthly to bi-monthly, the weekly Cybarite machine stored news sheet and the irregular Cyberflash continued, along with an introductory kit.

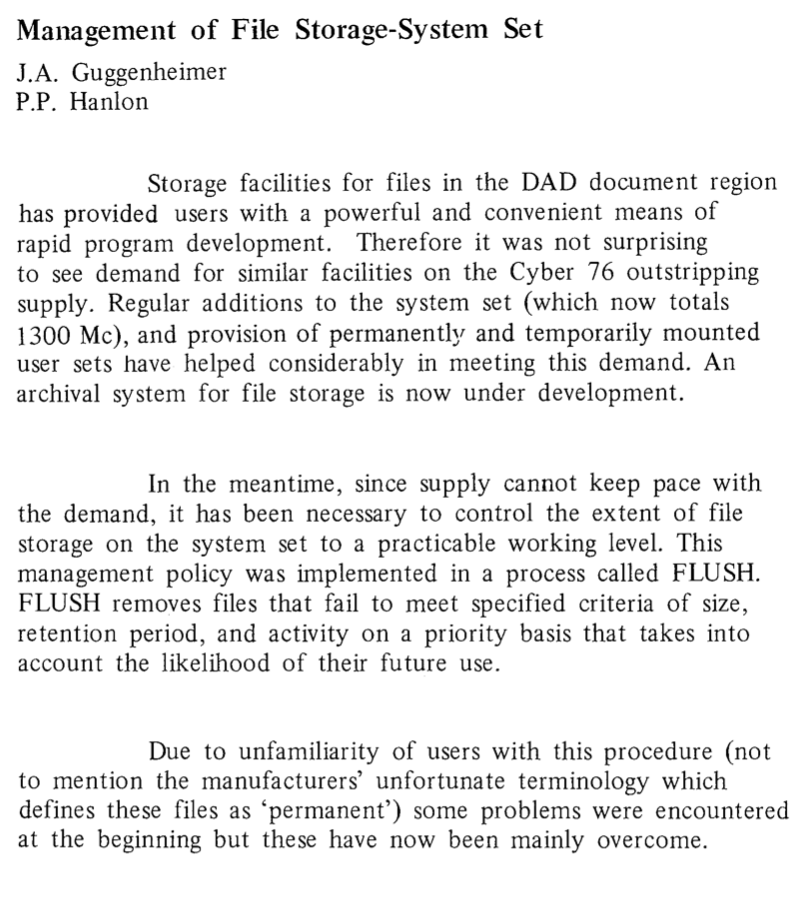

The SCOPE 2 operating system on the Cyber 76 supported permanent files – meaning files that could be requested to remain after the completion of a job. The term ‘permanent’ was unfortunate, because crashes could lose them. There was a story that one of the operators restarted the Cyber 76 with an incorrect date set, and happily answered the prompts to remove thousands of files marked as expired. The permanent file facility did not allow for many files, and this became a problem. Flushing was in operation, and a metric named ‘moribundity’ was used to select the most dormant files for removal.

With local nodes in operation, two DCR offices were closed, with operations being taken over by the local Divisions.

Finally, another expansion of the buildings was announced – 401C.

Back to start of 1977-78 Back to top

1978-79 – DCR, restructure, FACOM joint development project; M-190, NSC Hyperchannel and ATL; low-priority charges, improved resiliency, Ed libraries; CSIRONET: distributed services, links to USA, 96 nodes; new computer hall under construction, visitors to User Assistance

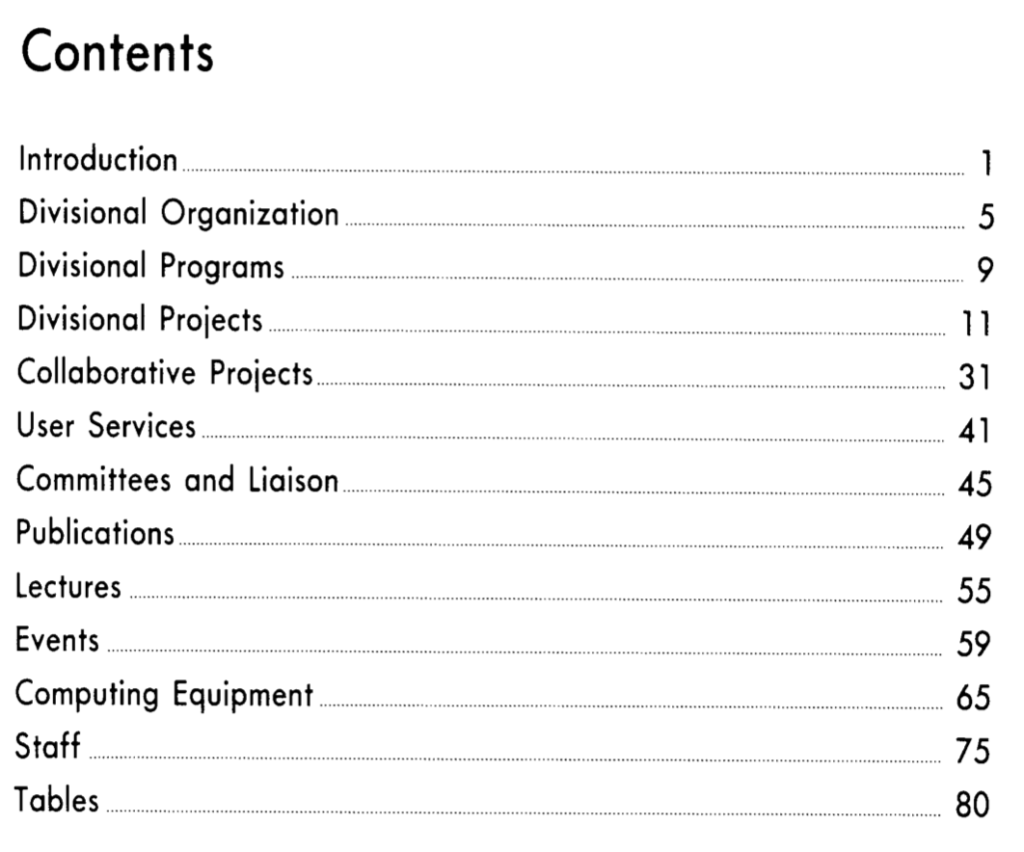

The 1978-79 DCR Annual report can be found here (82 pages).

Here is the contents page:

The Chief’s review started with plans for a structural change and a strengthening of the R&D capability.

As the networking capabilities spread, it was feasible to establish R&D sections away from Canberra, but the Rockhampton office was closed.

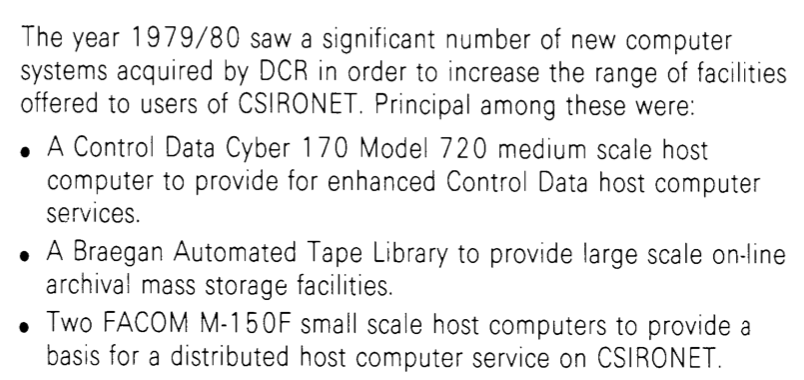

This year was the start of the Fujitsu/FACOM era, with a joint R&D agreement, and DCR acquiring ‘mainframe’ capabilities more suited to data processing compared with the scientific computing power of the CDC systems. The development of capabilities around the NSC 50 Mbit/s Hyperchannel was the first project: contrast that speed with the interstate links of 48 kbit/s.

Here is a brochure for the FACOM M-190.

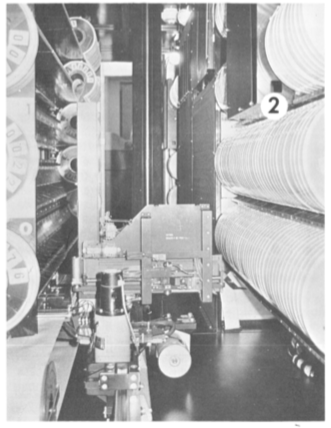

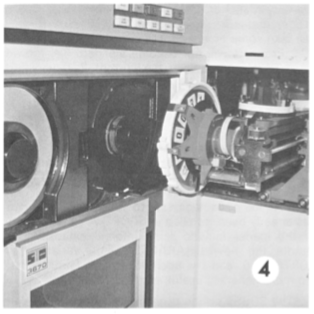

Automation of tape mounting in support of archiving started with the installation of a Calcomp/Braegan robotic tape mounting system. This used 9-track STK round tape drives, with tape capacities around 160 Mbyte.

Recruitment was restarted. No doubt the funding from the joint project helped.

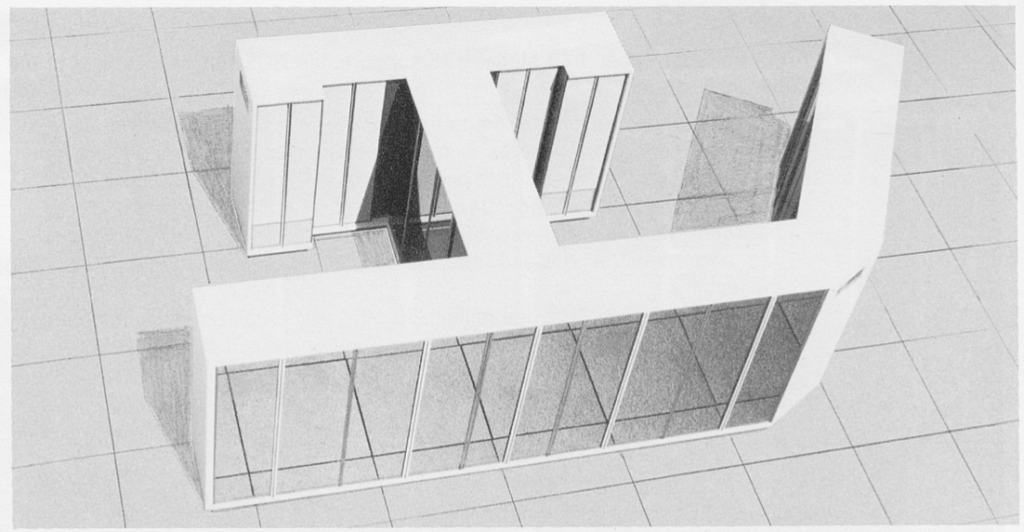

The new computer hall was underway – a unique design spanning a creek.

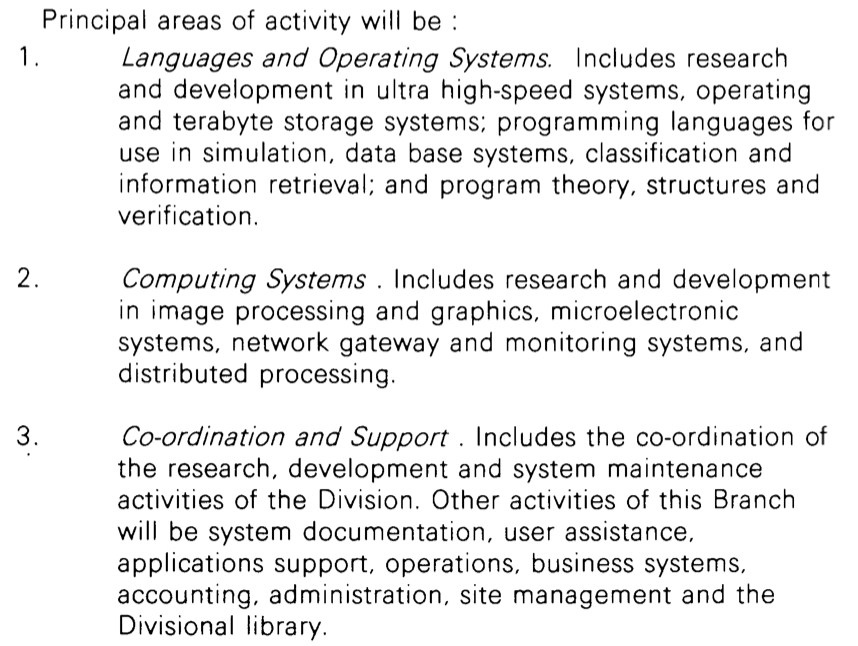

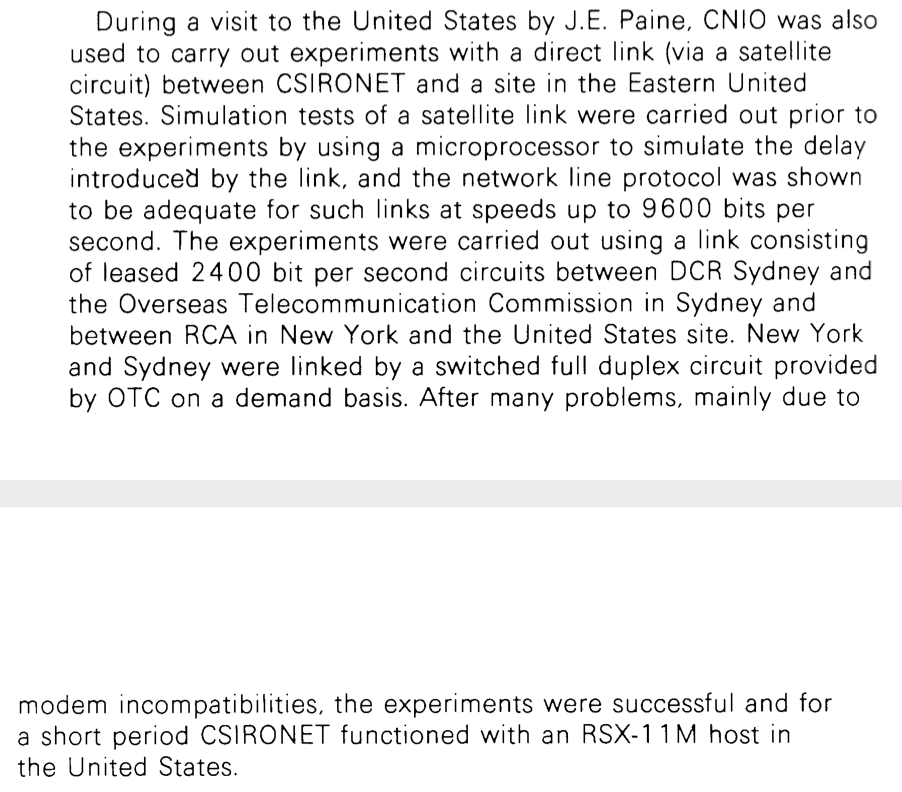

The network was spreading to remote areas, and being interconnected to international networks.

Low-priority (and low-cost) computing had a big uptake, and was immensely popular with large users.

The Annual report included a photograph of Mr Maston Beard, with the caption “former Assistant Chief”. Curiously, there was no other mention in the report. The csiropedia article on Maston Beard contains: “He retired from CSIRO in 1978 while Assistant Chief at the Division of Computing Research. Following his retirement he served as a Senior Research Fellow in the CSIRO Division of Radiophysics.”

He was the co-builder, with Trevor Pearcey, of CSIRO Mk 1 (CSIRAC).

Details of the proposed reorganization were given, emphasising the research focus.

Developments were underway to allow CSIRONET to function and be controlled and monitored from multiple disparate hosts – especially PDP-11 systems running RSX-11. The i/o package, the Monitor and Alarm System, and the Network Information Logger were early examples.

The first instance of an overseas CSIRONET node was reported.

Dial-up capability was an important advance for remote access.

With networks and the interfaces being far less reliable than today, the ability of the network to reliably restart output was an important advance.

DCR continued to undertake hardware developments to support the service, and was increasingly using microprocessor technologies. It had the expertise to find errors in equipment design and to design and build a terminal concentrator.

The first permanent interconnect was established with the MIDAS network.

CYI was the main interactive system running on the Cyber 76 – an entirely CSIRO DCR development, unlike any other in the world on a 7600 or Cyber 76. Support for 100 interactive users by the end of the 1970s was a major achievement, albeit with far slower communications links and limited capabilities, with most applications being text based. But, Tektronix graphical terminals were supported. With statistical analysis and artificial load generation, the limitations of file accesses under SCOPE 2 was uncovered.

Two major changes were made to circumvent these issues. The first was the development of the ED editor to support library files. These were originally in SCOPE 2 to support libraries of relocatables – compiled code of subroutine libraries, etc (partitioned data sets in IBM terminology). Whereas SCOPE 2 provided for permanent files to have filenames of up to 40 characters, and supported multiple cycles of files, the names of the members of a library could be at most 7 characters long, and had no cycle concept. DCR enhanced ED in many ways to support saving files in, retrieving files from, and auditing the contents of libraries. And, some genius provided a facility so that the Ed libraries could support a comment of up to 70 characters on each member. This became an excellent way to start building metadata around files, since users found that the 7-character limit was indeed very limiting (just as DOS not many years later was restricted to 8-character filenames, albeit

with a three-letter extension).

Workfile recovery was another major advance – less use of the PFM, and greater resiliency for users.

Here is an example of an audit of an ED library, showing the member names, the sizes, the type, the creation date and time (not Year-2000 ready!, but at least in the year-month-day order) and the comments. An important concept, intended to make up in some way for the loss of the cycle capability, was the facility for BACK-UP partition – a copy of the previous version of any partition that was updated, and retaining the comment. Audits could be sorted by name or creation date in forward or reverse order.

LIBRARY ABM20EL LENGTH 170 UNUSED 0 ENTRIES 42 NAME SIZE T CREATION CHKINST 1 A 820708 0854 JOB TO CHECK INSTALLATION JOB (UPDATE). UPDATE 4 A 820707 1639 JOB TO UPDATE THE UPDATE LIBRARY OF PROGRAM ALPHBET (AB). AB.DOC 8 A 820707 1613 DOCUMENTATION OF MODIFICATIONS TO PROGRAM ALPHBET. MODS20 4 A 820706 1414 JOB AND MODS FOR AB.PL CY=20. FIXFORCE. RUNMODS 2 A 820706 0928 JOB TO DO A TEST RUN OF MODS TO PROGRAM AB. BACK-UP 3 A 820702 1157 JOB TO UPDATE THE UPDATE LIBRARY OF PROGRAM ALPHBET (AB). SELECT 4 A 820629 1217 PROGRAM SELECT. MODS19 4 A 820623 1136 JOB AND MODS FOR AB.PL CY=19. PRINTTE. ABGRAF 5 A 820622 1001 JOB TO SET UP PROGRAM ABGRAF TO GRAPH FUNCTIONS OF TIME. .............

Of course, all the member names and metadata was in upper case only, but the contents were in ASCII mode supporting the ASCII character set.

So, we had a mechanism to consolidate files for a project into a single permanent file, had a backup facility to guard against immediate errors, showed dates, and allowed an extremely useful metadata facility. Linux still lacks a universal extended metadata facility.

It was another 20 years before CSIRO first set up a committee to look at metadata for its data holdings!

(Astute readers may notice the mention of UPDATE, and partitions whose names started with MODS. UPDATE was the CDC source code control system (later also provided by Cray Research), and MODS were sets of changes to to a library of code, either to be made permanent, or to provide temporary changes for testing, etc.) Source code for the operating system was delivered using UPDATE, with DCR then having to reconcile local modifications with changes from CDC. Any text could be stored in UPDATE, and so it was able to provide source code control for scripts and jobs as well as for source for compiled languages. A large debate around the use of UPDATE erupted in the CSIRONET community in a few years.

Here is a partition called MODS1, which set up an initial UPDATE program library. Note that upper and lower case could be used, but I suspect at the time of job submission, the lower case was converted to upper case.

makeupd(P1,T10) <<<<< Robert Bell >>>>>

Comment. Job to make an update library of program alphbet (ab).

GETSET,CMP9007.

attach(proclib,,id=cmpxrb)

library(proclib)

fuse.

attach(lib,$ab.el$,id=cmpxrb)

borro(p=kate1)

return(lib)

request(newpl,*pf,sn=cmp9007)

update(l=a123,n)

catalog(newpl,$ab.pl$,id=cmpxrb,rp=999)

*EOR

*skip cpy

*deck all

*read cpy

Both the network and the RIO system had to be enhanced to support the recovery mechanism.

Work commenced on the Joint Development Project with FACOM (the trading name used by Fujitsu for its computers).

Visits by staff from other CSIRO Divisions to DCR Canberra were facilitated, and reported to “have been of considerable mutual benefit”. (I certainly enjoyed my time at DCR, despite the mid-winter cold in Canberra, and learnt a lot.)

Finally, here are the headings under the Collaborative Projects section: this gives some idea of the diversity of applications, but does not include Divisional and government projects that did not involve DCR staff directly, so the range of applications will have been even wider. For example, the Division of Atmospheric Research in later years became one of the biggest users of CSIRO’s scientific computing services, but does not appear to have figured in any collaborative projects with DCR.

1. COLLABORATION WITH DSIR, NEW ZEALAND

2. COLLABORATION WITH U.S. NETWORKS

3. PROGRAM VERIFICATION

4. FORMATION OF SULPHIDE ORES

5. POTATO GROWTH

6. ARID-LAND REGIONAL MODEL

7. NUTRIENT UTILIZATION IN SHEEP

8. WOOL CRIMP

9. MODELLING THE FLOW OF CARBON THROUGH AN ECOSYSTEM

10. WEEVIL INFESTATION IN GRANARIES

11. SISDIM – Software for Integrating Spatial Data by Images

12. USE OF LANDSAT IMAGES TO MAP FOREST FIRES

13. GEOMETRIC CORRECTION OF IMAGES

14. STRUCTURE OF BACTERIAL REGULAR SURFAGE LAYERS

15. MUSCLE STRUCTURE

16. ELECTRON MICROPROBE ANALYSIS

17. COMPUTER MAPPING SOFTWARE

18. COMPUTATION OF SHAPE

19. COLOUR IMAGE PROCESSING

20. ROSS CASSETTE DATA PROCESSING

21. PASTURE SPECIES SITE CLIMATIC PREDICTION

Back to start of 1978-79 Back to top

1979-80 – DCR, typesetting, new systems – lower Cyber, ATL, FACOMS; building delay; CSIRONET: 102 nodes, inter-networking, Mail, microprocessors

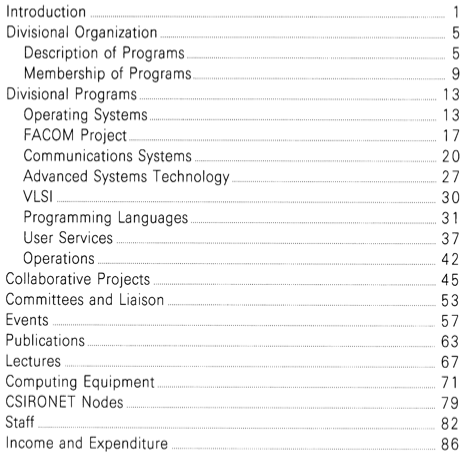

The 1979-80 DCR Annual report can be found here (88 pages).

For the first time, the report was prepared using the COMTEXT package developed by DCR and the COMp 80 system.

Here is the contents page:

More illustrations were included than before.

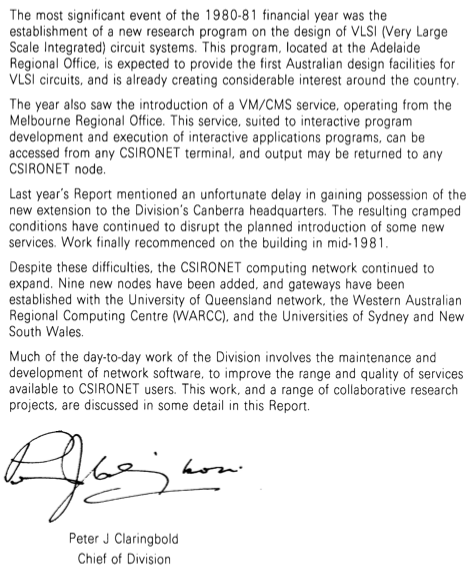

The introduction highlighted the restructure, the new equipment, the failure of the new building contractor, and the growth in users and connections.

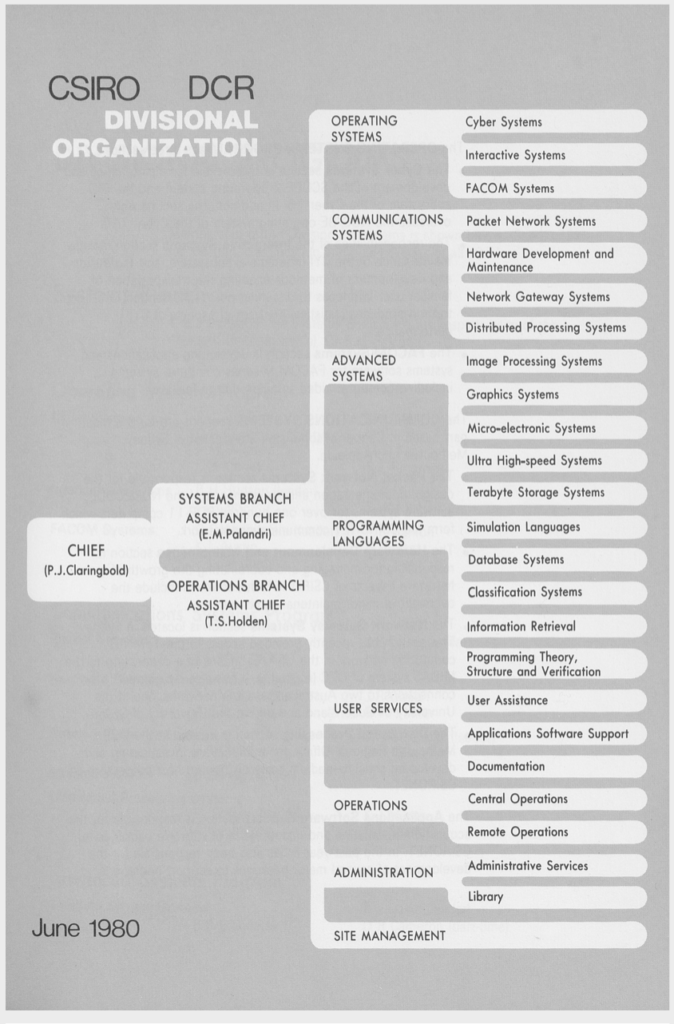

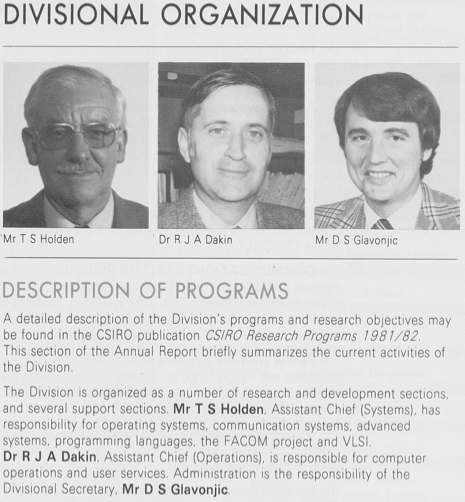

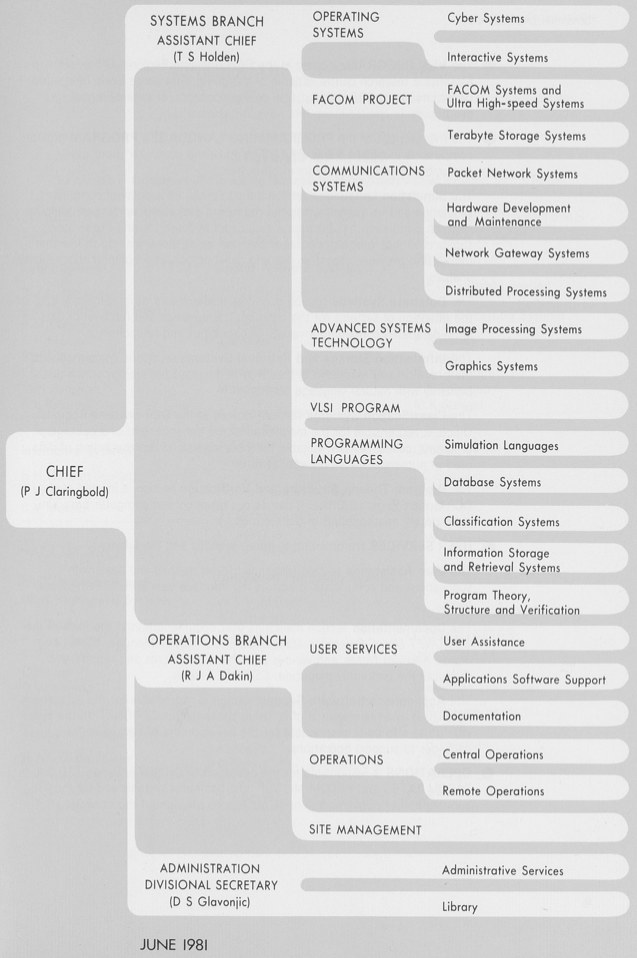

Two assistant Chiefs, Mark Palandri and Terry Holden, were appointed in the restructure, which is best summarised in the diagram below.

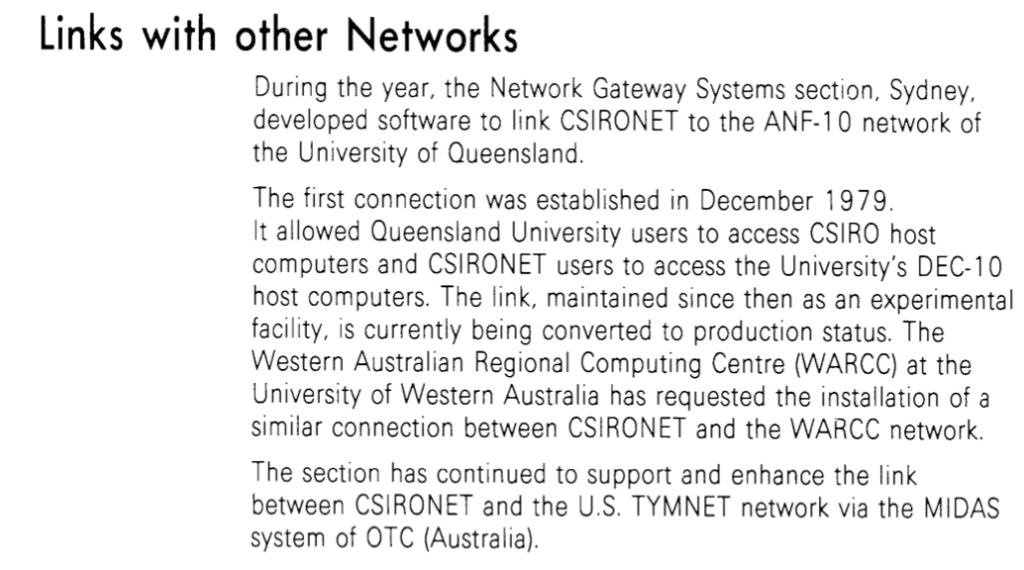

Advances were being made in links to other networks.

Diversification continued, with investigations into running an IBM mainframe operating system, geared to interactive use.

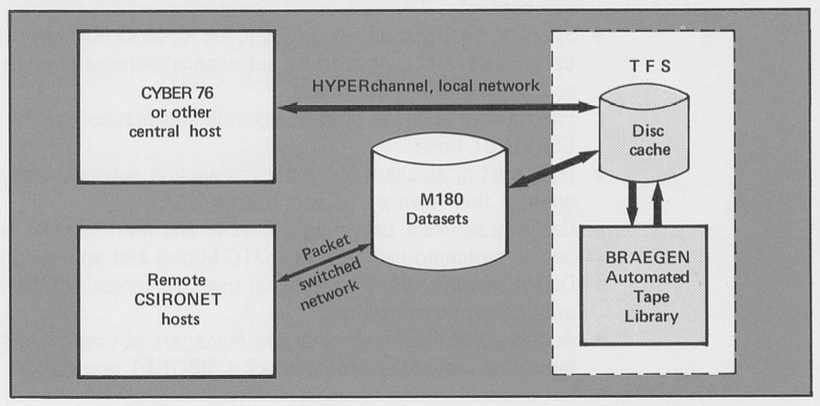

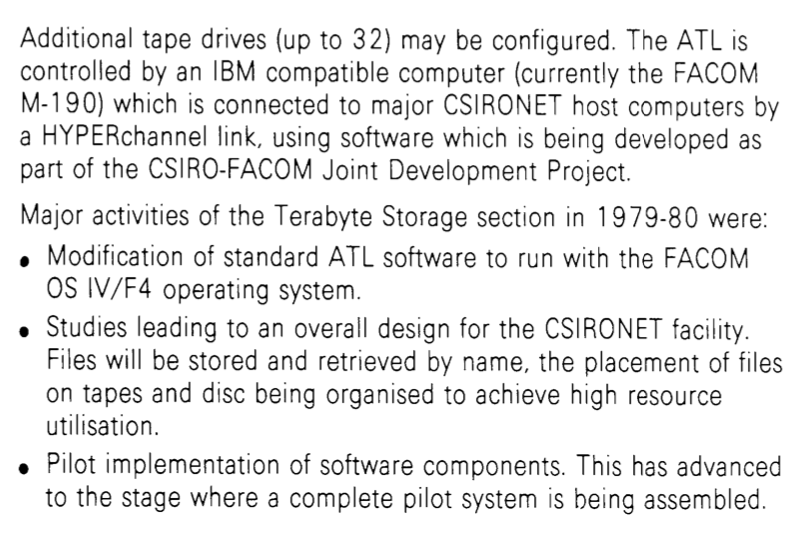

Although the ATL was installed, considerable software development work was being undertaken to build a network-connected multi-host data storage system on top of the FACOM computers and the tape library.

The next item headed ‘General Purpose Workstations’ would suggest a system to sit on users’ desk or be available in shared areas or laboratories, but instead resulted in the acquisition of two small mainframes.

(A picture of an M150F in Australia can be seen at http://userweb.eftel.com/~cantwell/clytech.htm ).

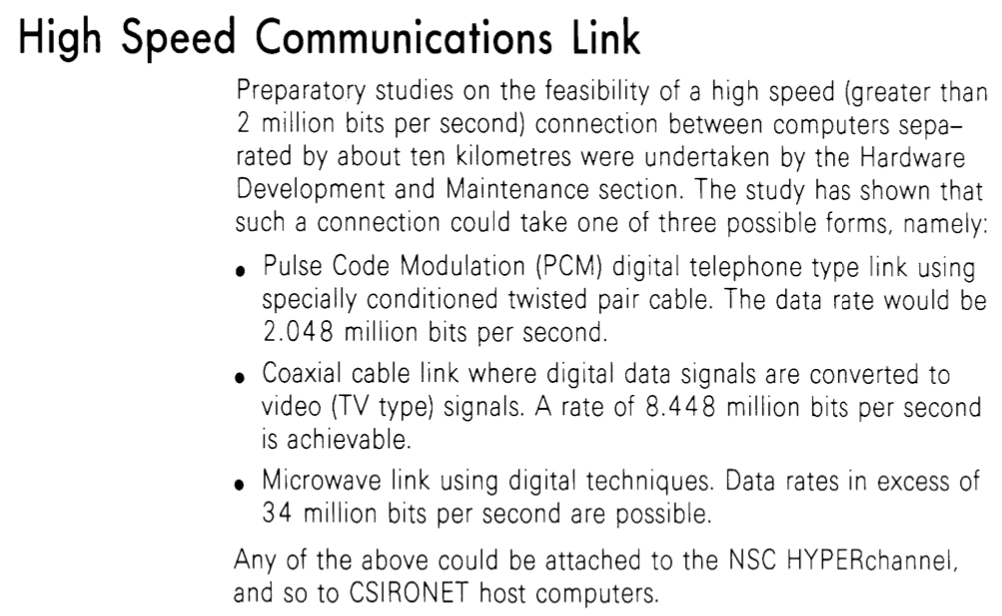

Investigation commenced on high-speed links between widely-separated computers. The 34 Mbit/s microwave links came into use in CSIRO in the 1990s for linking CSRIO sites in metropolitan areas.

Storage services continued to evolve to take advantage of newer technologies. The subsets were like the later /data areas – shared between several users in a group, with no backup or flushing, leaving the management to the group members – absolving the service provider (in this case DCR) of the need to manage the holdings before the storage area filled.

The NOS/BE OS was one of several operating systems available on the ‘lower’ Cybers – i.e. not the 7600 or Cyber 76 or the later Cyber 176. Each new system needed work before it could be integrated into the CSIRONET environment, and made available to users. The report also described the project to link the two Cybers via the Hyperchannel.

I’ve omitted the details of the achievements so far of the CSIRO-FACOM Joint Development Project, which included channel connections between the FACOMs and Cyber 76, the connection of CSIRONET terminals to the FACOMs, the installation of accounting systems, the development of a software design methodology, and the sharing of tape drives.

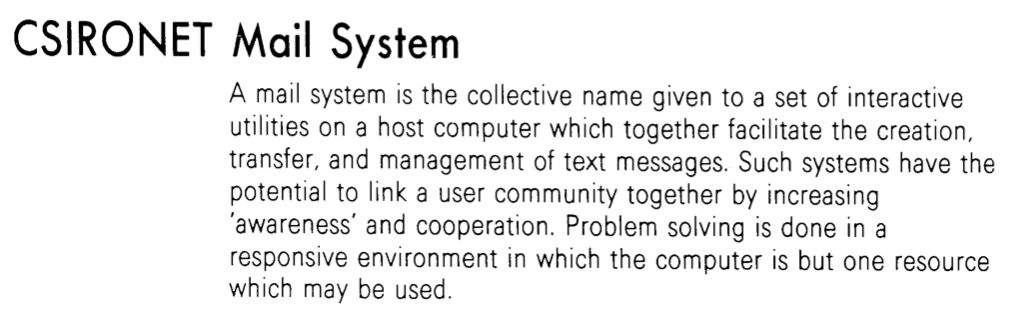

A Mail system was under development.

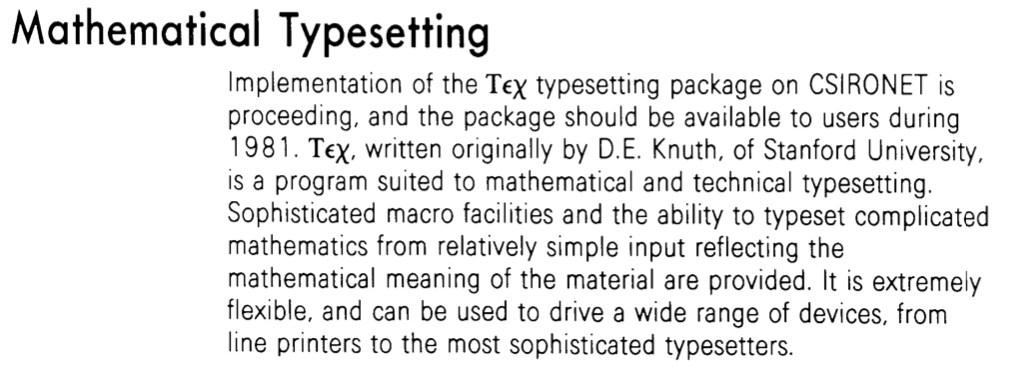

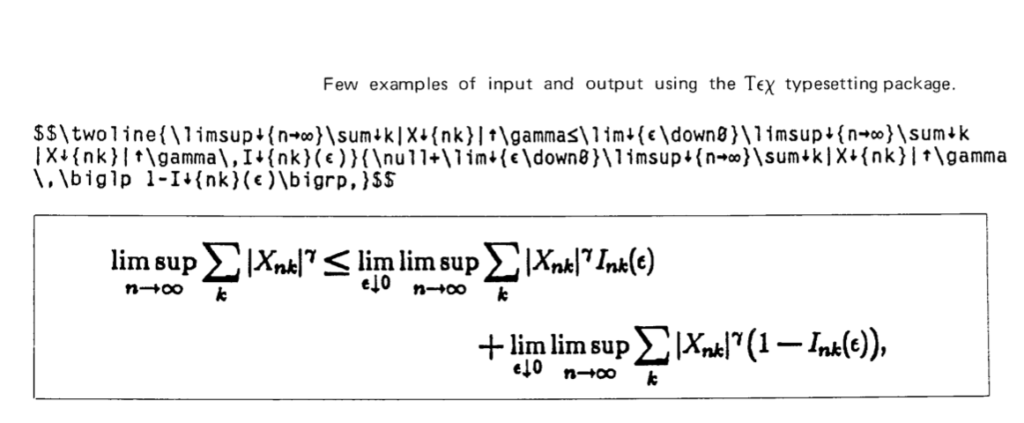

Don Knuth’s Tex package was being implemented on CSIRONET. As well as the COMTEXT package being available, Mike Dallwitz of the Division of Entomology had written and made available a package called Typset, which I used to typset one scientific paper.

Both exchange of software and the possibility of linking the two organisations were on the table.

Both exchange of software and the possibility of linking the two organisations were on the table.

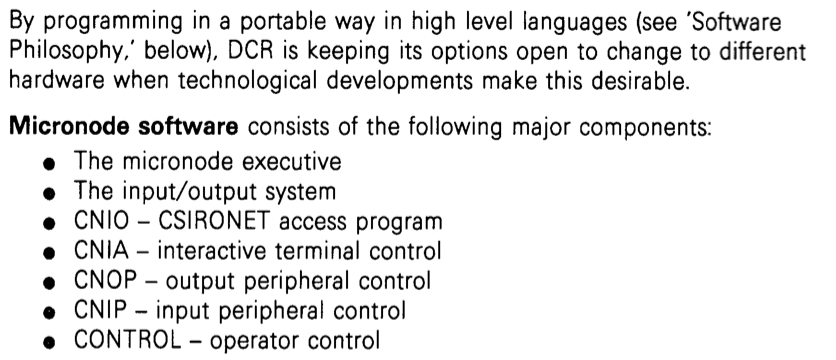

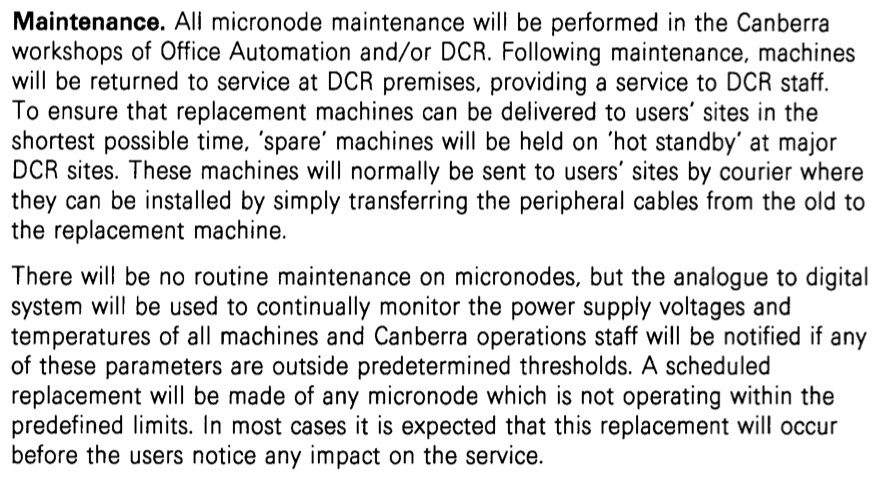

Developments using microprocessors were underway – these would lead to the development of the micronode, a far cheaper platform for CSIRO nodes than a PDP-11.

Another interesting project was the following:

Turing’s paper dated from 1952, not 1956.

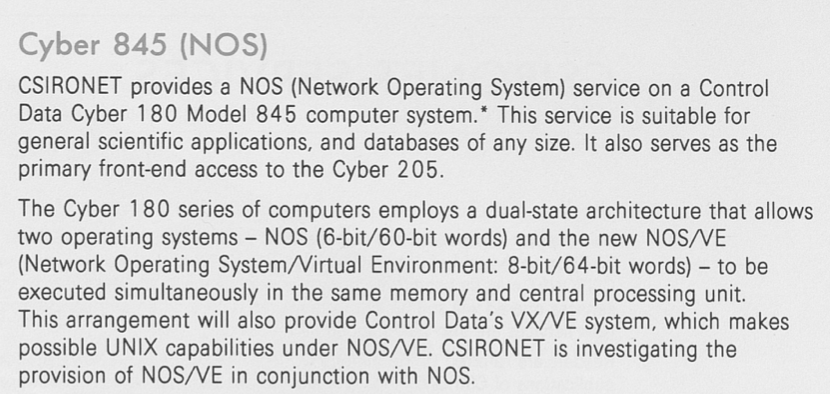

The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis (1952) Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 237 (641): 37–72.